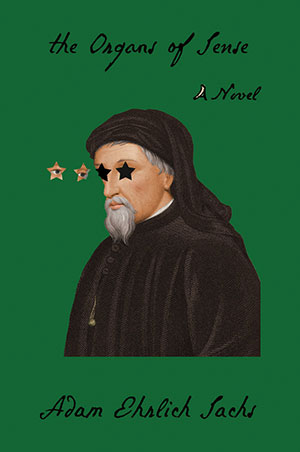

The Organs of Sense by Adam Ehrlich Sachs

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2019. 240 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2019. 240 pages.

Commencing Leaving the Atocha Station with a sharp gesture, novelist Ben Lerner puts all his narrative and descriptive responsibilities aside, in favor of a very funny use of vernacular language, when his protagonist follows a man carefully until the moment where the latter “totally lost his shit.” Lerner so clearly flags his shirking of the demands ordinarily placed on a novelist that the book as a whole comes alive and for its remainder doesn’t settle for anything less.

Adam Ehrlich Sachs in his new book, The Organs of Sense, his debut as a novelist, does something similar. However, where Lerner is content with giving his reader one heads-up at the very beginning, Ehrlich Sachs indulges in driving his story off a narrative cliff again and again. Such detours go back to the substantial conceit of Erlich Sachs’s book, as The Organs of Sense stages a fictional encounter between the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, portrayed at the age of nineteen, and a mysterious, blind astronomer, both anticipating an eclipse predicted by the latter to take place at noon, June 30, 1666. Relentlessly, the fabric of narrative gets cut off in this mise-en-scène wherein, crucially, Leibniz is the auditor of fiction.

The Organs of Sense is peppered with comic sequences wherein a particular word or phrase is robbed of its meaning by repetition; simultaneously, these segments are importantly put before the philosopher Leibniz at an impressionable age. A sculptor ecstatically confident at creating a perfect model of a human head (“I can make that head. I can make that head. I can actually make that head!”), an emperor quizzing the agent who purchases art for him about the fish on a particular painting, or the astronomer, celebrating the appearance of a new star in the night sky, going out in the streets of Prague to tie into knots the Aristotelians who thought that celestial bodies were eternal—these are but a few examples of how Ehrlich Sachs disrupts important assumptions involved in reading a contemporary novel.

So unlike the extremely self-aware and postmodern Lerner, Ehrlich Sachs, with his total commitment to completing every single skit, resembles older writing—bawdy tales from Gogol’s Dead Souls or Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel—and thus displays a modern attitude. Indeed, this motif is pursued so consistently that The Organs of Sense is something halfway between a novel and a piece of conceptual art.

There is much here to remind us of Ehrlich Sachs’s earlier collection of “stories, parables and problems,” the fantastically funny Inherited Disorders. Yet the most important connecting motif is the botched attempts, intellectual or violent, between fathers and sons at getting inside one another’s heads.

So what does this meeting with a blind, crazy astronomer mean for the philosopher Leibniz? It is quite wonderful to contemplate The Organs of Sense as the tragicomic illustration of Leibniz’s universe of self-contained monads between which no communication is possible.

Arthur Willemse

University of Maastricht