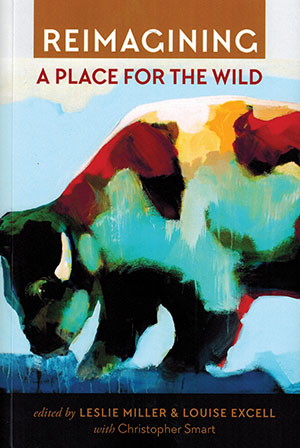

Reimagining a Place for the Wild

Salt Lake City. University of Utah Press. 2018. 352 pages.

Salt Lake City. University of Utah Press. 2018. 352 pages.

Arranged in four thematic parts, Reimagining a Place for the Wild is a collection of essays and narratives that ranges across disciplines and occupations. It includes contributions from a diverse group: naturalists and ranchers, environmental lawyers and easement agents, writers and biologists. Some of these authors approach the issue of wildness from opposing angles, but all are genuinely concerned for a sustainable and wild North American West. Though the collection is unmistakably regional, many of these same concerns are repeated wherever civilization and nature must coexist; this book appeals to a much wider audience than westerners or ecologists only.

The concerns for conservation raised here are as diverse as their authors. Rancher Yvonne Martinell’s “Ranching Communities and Conservation Must Be Combined” is not so much an argument as a narrative, which insists that her family and business are part of this landscape, not separable from it. Martinell describes, as an example of ranchers’ commitment to conservation, the extra expense she pays to protect her herds from wildlife diseases. But Robert B. Keitner notes that fears of brucillosis are often used to restrict the movement of Yellowstone’s bison, and the restrictions put on that rare herd’s range pose a threat to their species’ viability. Meanwhile, John D. Varley finds wildness in Yellowstone at an entirely different scale—a biologist and field researcher with decades of experience, he studies newly discovered microfauna at the bottom of the park’s deep lakes.

Reimagining a Place for the Wild deserves a place in the canon of American ecological literature alongside the likes of Muir, Leopold, and Carson. In fact, Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature comes to mind immediately for comparison. Thirty years ago, McKibben lamented the end of wild places. No place on earth was left completely free of human influence; however, when contributor Jeremy Schmidt describes a wild place he cherished in childhood, his memory includes the “low, labored sound of a tractor working” in the distance. For the writers in this collection, their imagination of the wild includes its people, too.

As Wendy Fisher notes in her contribution, wild places in this century must be managed if they are to survive. This reimagined wild cannot be a place where humanity has no presence. Instead, Reimagining a Place for the Wild inherits the viewpoint of the poet Robinson Jeffers, who wrote often about the invincibility of nature. As Jeremy Schmidt writes in “Waiting for Wolves,” “Wildness is everywhere. It is part of us. . . . Wild creatures might disappear. Wildness will not.”

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University