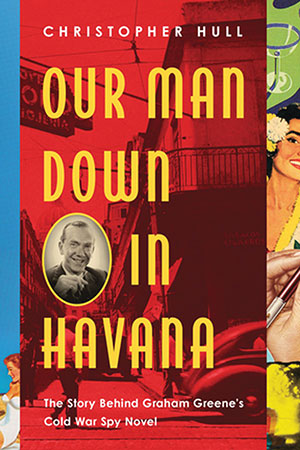

Our Man Down in Havana: The Story behind Graham Greene’s Cold War Spy Novel by Christopher Hull

New York. Pegasus Books. 2019. 338 pages.

New York. Pegasus Books. 2019. 338 pages.

Our Man Down in Havana pulls out some threads from the complex story behind the writing of the famous satirical novel Our Man in Havana (1958), which was later made into a 1959 film. The idea of writing Our Man in Havana was conceived when Alberto Cavalcanti, a Brazilian film director, asked Greene to write a film outline, way before the Cuban Revolution. Our Man in Havana satirizes “Britain’s self-delusion about its standing in the world, the ineptness of government departments, and the cover-ups they concoct to distract from their cock-ups.”

According to Hull, British writer Graham Greene’s unplanned visit to Havana inspired him “to resurrect a decade-old outline for an espionage story.” Hull’s book has a greater scope than the title might suggest, tracing the historical context of the tensions between East and West, love, capitalism, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, inter alia. Greene’s biography provides Hull with a great opportunity to explore Cuba’s history during the 1950s and 1960s and the position of British intelligence on the island in sections such as “Down in Havana” and “Our Arms in Havana.”

Hull starts out by giving background information on Greene’s life, as the author drew upon his work as an MI6 officer in Sierra Leone and London to inspire his fictional world. Although Hull sometimes runs the risk of giving too many details of Greene’s biography, this account shows how the historical context gives Greene’s novel meaning and illustrates how the border between reality and fiction is blurred through the novel’s many kernels of historical fact. The novel’s protagonist, James Wormold, and his espionage world do not resemble Ian Fleming’s well-known “shaken-not-stirred” and flawless James Bond but more truthfully mimics spy agents during wartime: “farcical” and “funny.”

Hull adeptly fleshes out points of connection that often go unacknowledged. He draws attention to Our Man in Havana’s protagonist, who feeds his superiors with false reports and actual events such as the invasion of Iraq that was based on subsources, fabrication, and falsehood. From there, Hull sheds light on decisions that have been marked with massive mistakes. At the end, Greene and later Hull leave us with a fundamental question: What would we prefer to believe?

The data for this book was compiled from an extensive range of archival investigation and a thorough analysis of Greene’s biography and other works. From there, Hull narrates the story behind the novel of a famous writer who suffered from manic depression, focusing on historical anglo-American and Latin American relationships.

Christopher Hull’s latest book can productively appeal to researchers and students working on Graham Greene’s life and works as well as to those studying British policies in Cuba.

Toloo Riazi

University of California, Santa Barbara