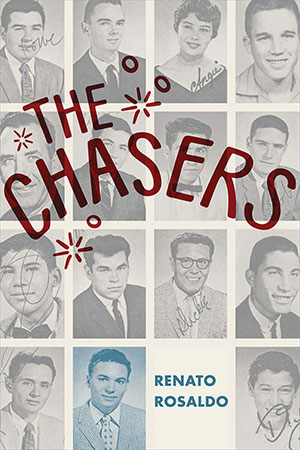

The Chasers by Renato Rosaldo

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2019. 144 pages.

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2019. 144 pages.

Renato Rosaldo established himself as an ethno-poet with his groundbreaking 2013 volume The Day of Shelly’s Death, which combined poetry, ethnography, and photographs to tell the moving story of his wife’s fatal accident decades earlier in Philippine backcountry. Now he gives us a new collection, also multidisciplinary. The Chasers is a deep-reaching account, in prose poems, of the high school gang to which the poet belonged when he was a student at Tucson High from 1956 to 1959.

An anthropologist as well as poet, Rosaldo describes this new book as auto-ethnography. Concept as well as language innovation make it as soul-wrenching as its predecessor. More club than gang, as the term is used today, the Chasers were twelve adolescent males searching for identity in a racist and classist time. Eleven were Mexican Americans, one Jewish, one from a family of migrant workers. The Chasers had their own jackets and immense pride. In a prelude, Rosaldo writes: “What I learned through participant-observation was not social description. It was personal . . . what it meant to be a Chaser, how it sustained us, how we sustained us, how they sustained me.”

It was at their fiftieth high school reunion that the eleven surviving Chasers (one was deceased by then) reunited and “remembered what we never forgot, what we held close, the people and places we never let go . . . once we resumed, we couldn’t stop gathering, looking back, unforgetting.” Memory is many-layered in these powerful poems. The men continued to meet. The idea for this book was born.

Who are these men today? The one no longer alive was a supermarket produce manager. The others worked as a field superintendent for a mechanical contractor, a marijuana smuggler, a fireman and paramedic, an artist and singer, two lawyers, an elementary school principal, a psychiatrist, a moving and storage estimator, a cultural anthropologist, and a neurologist. Two Anglo friends, also present in these pages, were a realtor and university professor. A woman close to the boys was a teacher and owns a religious store. Most have risen in life. All remain Chasers.

The Chasers is composed of brief prose poems in the voices of these boys-become-men. Their teenage identities sound through words spoken decades later. Rosaldo’s ethnographic skill and poet’s intuition are evident in the portraits he creates. Photos of each Chaser and their female ally add to the book’s multilayered feeling.

Given more space, I would reproduce several poems or fragments of poems. Lacking it, I want to quote from one. Here is Rosaldo, in “Observing,” speaking in his own voice: “I flopped the first time I tried to hard-ass. Failure shut me up, made me feel / like I did the day the word ‘elefante’ eluded me, as if my tongue had been pulled / out by the root. / In my family’s ’51 Dodge, I drove across town, east to west, house to house, / picked up the guys, hard-assing the entire trip. I remained mum, under a / bushel basket, no sign of me. / Bobby says, ‘Now that I mention it, Chico, I never liked you. / I said who the hell is this guy? I don’t think we voted anybody / out, but you, you were borderline.’ / Restoring my Spanish left me unable to master another language, the catlike / rapid swats of hard-assing. Instead I listened with all I had, became a quiet / guy, laughing, being an audience, observing . . .”

The Chasers is a must read.

Margaret Randall

Albuquerque, New Mexico