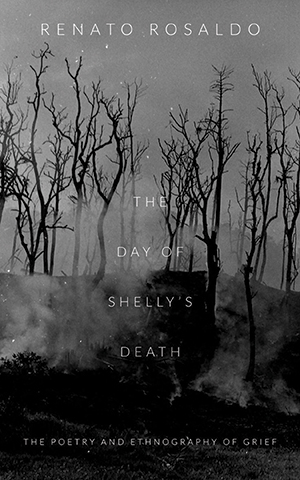

The Day of Shelly’s Death: The Poetry and Ethnography of Grief by Renato Rosaldo

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2014. ISBN 9780822356493 / 56615

When we lose a great love, our first impulse is to find a way through the grief—and the rage within the grief. When the loss is sudden, and perhaps especially when it wears the terrible clothing of “if only,” the grieving may take unexpected turns. All such loss, however it may strike, is traumatic. And, depending on the need, circumstance, and creativity of the person who has suffered the loss, it might emerge as art that can be shared with others.

When we lose a great love, our first impulse is to find a way through the grief—and the rage within the grief. When the loss is sudden, and perhaps especially when it wears the terrible clothing of “if only,” the grieving may take unexpected turns. All such loss, however it may strike, is traumatic. And, depending on the need, circumstance, and creativity of the person who has suffered the loss, it might emerge as art that can be shared with others.

On October 11, 1981, at the beginning of what was to have been several months of joint fieldwork in a remote region of the Philippines, Renato Rosaldo’s wife and companion anthropologist, Michelle (Shelly) Rosaldo, fell from a precarious trail to her death. Suddenly, the woman he loved was gone, their two small children motherless, their immediate and long-range future dramatically reorganized. It would be twenty-eight years before these poems emerged.

The book combines a timeline, two essays, photographs that bring the reader to the otherness of place (including a number of marvelous portraits), rough hand-drawn maps that attempt to trace the moment of disaster, important notes, an index, and, quite centrally, the poems. Many of these are written as imaginaries from the perspectives of his children (five years and fourteen months old when their mother died), a kind companion, an opportunistic “helper,” the forensic official, a field mouse, and the cliff itself. This is genre-bending in the most meaningful sense of the term, not because the author wanted to explore his subject matter in a variety of genres but because he has expertise in a number of fields, and that expertise very naturally rose to the surface here.

Dealing with loss is very much about memory. The Day of Shelly’s Death remembers. And it re-members, that is, it reconnects the pieces of broken, fragmented experience. In “The Ifugao Men,” we read about the moment Rosaldo is brought to where his dead wife’s body was found: “Conchita arrives // with a pale, trembling man. / He places his lips on the body’s lips, // rocks back. A fly buzzes / in then out of the body’s mouth.” This is but a taste of what is found here.

In the first of the book’s two essays, “Notes on Poetry and Ethnography,” he writes of his conviction that “The material of poetry is not so much the raw event as the traces it leaves” and “The ambition of poetry is . . . to be the event itself.” I heartily agree. And I believe Renato Rosaldo has achieved these aims magnificently.

Margaret Randall

Albuquerque, New Mexico