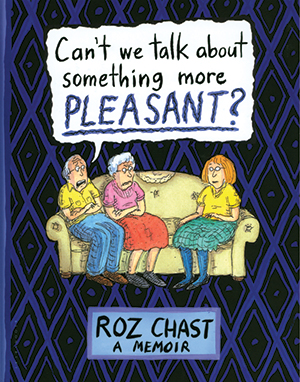

Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? A Memoir by Roz Chast

New York. Bloomsbury. 2014. ISBN 9781608198061

It is difficult to imagine tackling such a complex and emotionally wrought subject as preparing for one’s parents’ deaths in a graphic memoir, but that is exactly what Roz Chast does so brilliantly. It doesn’t matter if the reader is young or old, parent or child, this work crosses all boundaries to speak to some of our most human concerns.

It is difficult to imagine tackling such a complex and emotionally wrought subject as preparing for one’s parents’ deaths in a graphic memoir, but that is exactly what Roz Chast does so brilliantly. It doesn’t matter if the reader is young or old, parent or child, this work crosses all boundaries to speak to some of our most human concerns.

An only child, Chast felt very much the outsider to her parents’ soul-mate coupledom. They see themselves as a perfect match—“The rocks in his head match the holes in mine,” as her mother says—and a closed system, which may account for Chast’s distance from them for many years. But as an only child, she became responsible for their end-of-life decisions. Lest you think this was only a matter of arranging a funeral, it was not. Chast’s parents, who died in their nineties, needed to be coaxed out of their Brooklyn home pretty much against their will, and only when they could no longer take care of themselves, to be moved kicking and screaming into “the place.”

For anyone familiar with Roz Chast’s many drawings for the New Yorker, her often-quivering illustrations and emphatic use of punctuation, which seem to capture anxiety in every line and image, have become a signature style signaling wit and psychological insight. But there is no need to be familiar with her earlier work to be immediately drawn into this volume. Her mother’s adamant personality—giving those who displease her a “blast from Chast”—her father’s endearing demeanor even in the late stages of dementia, and her parents’ trove of saved articles (ranging from inoperable toasters to old eyeglasses to bankbooks from defunct banks) will draw smiling nods from readers.

In this achingly powerful examination of her life with her parents in their last years, Chast renders them so human that they are universal parents or aunts and uncles. As their lives grow smaller and their options fewer, we find ourselves mourning and laughing at once because, really, what else can you do when your mother has a closer bond with the Jamaican nurse than with her daughter? And can any child prevent the guilt that comes from thoughts about running out of money to care for her parents? Chast tackles all this and more.

The final drawings of her mother’s last days in bed shift from the cartoon-like earlier pages into the style of old master drawings, memento mori drawn with love and compassion. Examining feelings about parents is a lifelong project, and Chast portrays her own journey honestly and masterfully. Fortunately for us, she also provides acute insights and trenchant humor into the large question of how we confront mortality. There is little more one can ask of a work of art.

Rita D. Jacobs

Montclair State University