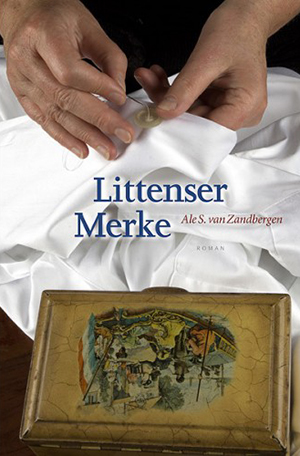

Littenser Merke by Ale S. van Zandbergen

Ljouwert, Netherlands. Friese Pers. 2013. ISBN 9789033004223

The reader of this debut novel will be surprised to get two stories for the price of one. Author Ale S. Van Zandbergen is indeed off to an ambitious and impressive start to his literary career. In Littenser Merke (The Littens fair), he juggles in alternating chapters the stories of a parsonage in the 1830s and the coming-of-age of a remarkable boy in the 1960s. The village of Littens is the locale for both stories.

The reader of this debut novel will be surprised to get two stories for the price of one. Author Ale S. Van Zandbergen is indeed off to an ambitious and impressive start to his literary career. In Littenser Merke (The Littens fair), he juggles in alternating chapters the stories of a parsonage in the 1830s and the coming-of-age of a remarkable boy in the 1960s. The village of Littens is the locale for both stories.

The Dutch Reformed Church in the early 1830s was roiled by the turbulence of Enlightenment ideas. Rev. Tinus Laurman, who actually lived there at the time, is the main character in the first story. Rev. Laurman is caught in the tension between an intellectual understanding of the faith, which he prizes, and an emotional experience that others insist on and which he denounces as fanatical. Disturbed over the loss of members in his Littens church, he joins forces with other like-minded clergy to turn the tide, even undertaking a long and tiresome journey to northern Friesland for help. In the process, the studious Laurman finds his own faith unraveling. Not unrelated is the unraveling of his marital bliss. As an intellectual introvert and frigid lover, he’s not on the same page as his wife, who’s an emotional sensualist and wants a baby. But Shakespeare was right: all’s well that ends well, and this story, though in a rather bizarre way, does.

The second story skips over more than a hundred years. Language, mores, social life, preoccupations, and much more have changed. But the Littens Fair is still the town’s annual highlight, and the church still stands in the same place. And here, too, the focus is on another odd “couple.” The reader is kept fascinated by the nine-year relationship between a somewhat autistic, naïve, but intelligent butcher’s son and a street-smart and world-wise hippy daughter of a struggling artist, who teaches the younger Liuwe about the ways of the world and introduces him to alternative pop music, books, new vocabulary, soft drugs, sex, and much more. Young Liuwe is somewhat like Laurman—introspective, cerebral, wondering about faith, and rather indifferent about sex. The meaning and order in his life that he seeks prove elusive. But it’s the dialogue between these two characters that makes the reading of this story especially a pleasure.

Fiction asks the reader to suspend disbelief. Verisimilitude makes that possible. The author’s authentic rendering of such disparate time periods and characters engages the reader’s imagination and enjoyment. Sometimes, however, the author allows his imaginative powers to run wild when he lets fantasy merge with the realism of the story. Then the bizarre stretches credulity, for instance in the escapades of the traveling minister and the minister’s wife making love to the artist’s leather jacket.

But more importantly, this new novelist has enriched the Frisian literary scene. Littenser Merke has been awarded the Douwe Tamminga Prize for best debut novel and the Rink van der Velde Prize for best literary work in Frisian. Readers may hope that there is much more to come from Ale S. van Zandbergen.

Henry J. Baron

Calvin College