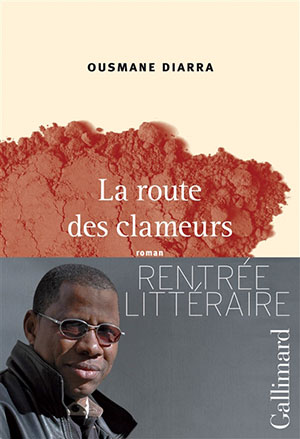

La route des clameurs by Ousmane Diarra

Paris. Gallimard. 2014. ISBN 9782070146284

In his third novel, Ousmane Diarra (who works as a librarian in Bamako) describes the disasters caused by the Islamic fundamentalists who have attempted to take over Mali. The story is narrated by an adolescent boy who begins with a description of the end of his father’s life, then returns to show how the terrorists persecuted his father and how he and his elder brother fought to save him.

In his third novel, Ousmane Diarra (who works as a librarian in Bamako) describes the disasters caused by the Islamic fundamentalists who have attempted to take over Mali. The story is narrated by an adolescent boy who begins with a description of the end of his father’s life, then returns to show how the terrorists persecuted his father and how he and his elder brother fought to save him.

The Malians see themselves as “nous autres Blacks nègres afro-afri-cains,” whom the foreign Islamists (often from the Middle East) treat with no respect. They impose sharia and take over the power of the traditional leaders; they speak only of death and the afterlife, never of beauty. The father mocks their ignorance; they want even to banish nonexistent Buddhists from the country. He refused to accept any fundamentalist doctrine but would not flee Mali with his paintings and sculptures when he had the opportunity. His art is judged pagan and destroyed. He is taken to meet the new leader, who had been his schoolmate, it turns out, the worst student in the class, but with money to buy all the television stations and newspapers. The false caliph’s name is repeated many times in the novel: “Caliphe Mabu Maba dit Fieffé Ranson Kattar Ibn Ahmad Almorbidonne.” Ironically, the names of the narrator and his father are never given.

In an attempt to save his family from a worse fate, the boy allows himself to be recruited into a terrorist group. He dreams of an ideal woman he will meet in paradise, but, against his better judgment, he participates in the killing of all the inhabitants in a village when he, like the believers, is drunk on blood and cocaine. In one village, when all the women and girls are gathered together to be raped, he finds that he cannot touch a child. When he is made a “page” to the caliph, he is forced to give his master drugs and to masturbate him. The final straw comes when the leader decides to divorce the boy’s parents and make his mother marry another fundamentalist man, to which the boy reacts by killing the caliph.

The narrative line has been reversed, with references in the first chapter to such events as the killing of the caliph that are only described much later in the novel. The boy and his father walk through the bush. The father knows the land and sees baboons that seem superior to humans, but the son has to teach him to avoid the land mines (“les oeufs de la mort”). The father dies after having reached Bazana, his native village.

The effect is one of uncertainty. Although the father dies, what will happen to the young narrator? Will Mali be able to defeat the fundamentalists? The ending leaves the reader with no resolution.

Adele King

Paris