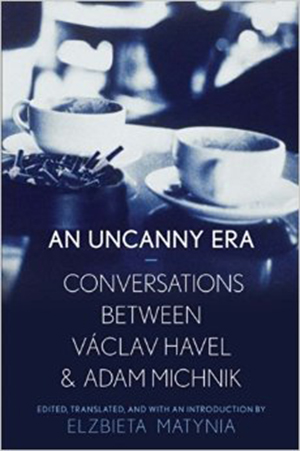

An Uncanny Era: Conversations between Václav Havel and Adam Michnik

Elzbieta Matynia, tr. New Haven. Yale University Press. 2014. ISBN 9780300204032

In 1978 eight dissidents met on a mountainside on the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland, countries under Communist rule since 1948 and 1945, respectively. Among them was Václav Havel, a Czech playwright and founder of Charter 77—a loose organization of Czechoslovak intellectuals and artists fighting for the protection of human rights under the communist regime. Adam Michnik, a Polish attendee, was already championing the underground press in Warsaw and the Workers’ Defense Committee, the first major anti-Communist organization in Eastern Europe. Both men had already been in prison for their misconduct against the state, and both still had significant prison time ahead of them.

In 1978 eight dissidents met on a mountainside on the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland, countries under Communist rule since 1948 and 1945, respectively. Among them was Václav Havel, a Czech playwright and founder of Charter 77—a loose organization of Czechoslovak intellectuals and artists fighting for the protection of human rights under the communist regime. Adam Michnik, a Polish attendee, was already championing the underground press in Warsaw and the Workers’ Defense Committee, the first major anti-Communist organization in Eastern Europe. Both men had already been in prison for their misconduct against the state, and both still had significant prison time ahead of them.

That day in 1978, though, was the beginning of a friendship that lasted over thirty years. At the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, Havel became the last president of Czechoslovakia and subsequently the first president of the Czech Republic, serving until 2003. Also in 1989, Michnik founded Gazeta Wyborcza, the dominant political newspaper in Eastern Europe, and worked as its editor in chief until 2004. An Uncanny Era serves as a window to that friendship between Havel and Michnik, two men who became key figures in post-Communist Europe. The book consists of a thorough introduction by translator Elzbieta Matynia, six conversations, two letters, and an essay, all documenting the massive political changes and social issues of the day through the eyes and words of two passionate and influential people.

Michnik, ever the journalist, carefully guides each conversation, and the most pressing issues, political or social, local or worldwide, are carefully unfolded and examined on each page. Michnik’s questions give way to lively debates, and both men consistently find ways to surprise. Along with the difficult transition into democracy both of their countries face, they discuss fascism, religion, abortion, Putin, the media, Islamic extremism, Clinton, music, art, self-image; the list goes on. Each conversation, separated by years, shows the development of the political and social setting as well as Havel’s and Michnik’s own causes, hopes, and predictions for the future. The book lends itself to separated reading; each conversation stands alone. And although some sections move more slowly than others, the ideas and topics build and develop nicely across the years.

As a whole, though, the book is not simply interesting and informative: An Uncanny Era serves as a celebration of humanism, intellectualism, passion, and political activism. The candor, intelligence, and humor of Havel and Michnik shine through, even in translation. Their conversations and correspondence lend texture and humanity to an already fascinating and significant era of European history.

Katie Garbarino

University of Oklahoma