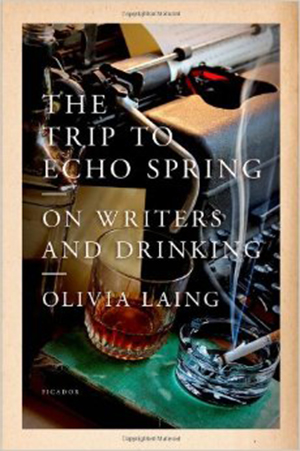

The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking by Olivia Laing

New York. Picador. 2014. ISBN 9781250039569

Alcoholics offer various reasons for their addiction. Fitzgerald believed, or rationalized, that liquor heightens the emotions, enabling him to make his fiction “felt” rather than “reasoned out.” To Hemingway, alcohol was the Giant Killer, able to annihilate any fears that might paralyze creativity. Tennessee Williams was more direct: you drink because you’re “scared shitless of something” or “can’t face the truth about something.”

Alcoholics offer various reasons for their addiction. Fitzgerald believed, or rationalized, that liquor heightens the emotions, enabling him to make his fiction “felt” rather than “reasoned out.” To Hemingway, alcohol was the Giant Killer, able to annihilate any fears that might paralyze creativity. Tennessee Williams was more direct: you drink because you’re “scared shitless of something” or “can’t face the truth about something.”

The book’s title derives from a euphemism in Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof that Brick uses for the liquor cabinet, which provides him with the means of hearing the “click,” the signal that he has arrived at a state of nirvana that temporarily burns off the mist of mendacity hanging over Big Daddy’s plantation. The Trip to Echo Spring is Laing’s personal odyssey, inspired by John Cheever’s mythic short story “The Swimmer,” in which Neddy Merrill decides to swim his way home, as if his neighbors’ pools were a river cruise with stopovers where he could drink, when welcomed. Toward the end of his journey, either no liquor is available or it is denied him. When Neddy finally arrives home, it is not where the heart is; it is where no one is—just a shell of a house. Cheever makes Neddy’s homeward journey, with its periodic breaks, a metaphor for blackouts, rendered gracefully at first, like slow-motion swimming, and ending in a close-up of unforgiving reality.

Laing has fashioned her extra-ordinary work as a travelogue that took her from England to Cheever’s New York and the Elysée Hotel in Manhattan where Tennessee Williams died. From there she traveled to New Orleans, the setting of Williams’s greatest play, A Streetcar Named Desire, then to Key West, beloved of Hemingway and the site of Williams’s conversion to Catholicism. Her final stop is Port Angeles in Washington, where her journey ends at Raymond Carver’s grave.

Like Neddy Merrill’s, Laing’s is an odyssey of discovery of both self and other—an attempt to come to terms with the addiction that plagued her mother’s partner and the unassailable Giant Killer that laid low those too weak to slay it. Laing writes like a novelist, linking her writers together when she can, as if they were all swimming in Neddy Merrill’s network of pools, communicating with one another—Cheever with Carver, Fitzgerald with Hemingway, Williams with Hemingway. They all have a common bond besides alcohol: genius. Perhaps they needed the “click” to produce what they did. Regardless, we are all the better for it.

Bernard F. Dick

Fairleigh Dickinson University