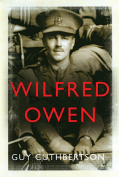

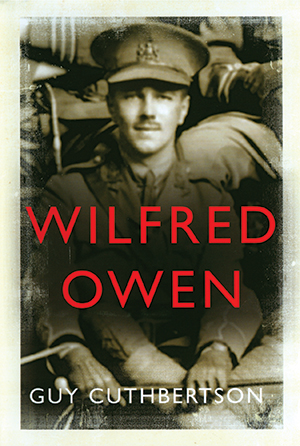

Wilfred Owen by Guy Cuthbertson

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2014. ISBN 9780300153002

As a young man of twenty-one, Wilfred Owen remained the boy who posed in a family snapshot as a proud soldier with gun in one hand, sword on his belt, military tent nearby, when he wrote: “After all my years of playing soldier, and then of reading history, I have almost a mania to be in the East, to see fighting, and to serve.”

As a young man of twenty-one, Wilfred Owen remained the boy who posed in a family snapshot as a proud soldier with gun in one hand, sword on his belt, military tent nearby, when he wrote: “After all my years of playing soldier, and then of reading history, I have almost a mania to be in the East, to see fighting, and to serve.”

Owen died at age twenty-five, a week before the Armistice in 1918, sealing his reputation as one of Britain’s most endearing poets. He had the ability to be mature beyond his years: he wrote “sophisticated, inventive, courageous, original work.” There was also the Owen of “arrested development,” a determination to improve and educate himself, to achieve “progress.”

His life was short, dying bravely leading his company across the Ors Canal under unrelenting machine-gun fire. His parents received the fatal telegram at noon on November 11.

His childhood was solitary, bookish. He had an enquiring and artistic attitude. He was, throughout his short life, very close to his mother. His brother, Harold, remarked, “Wilfred had only one reliable relief from loneliness, the solace which my mother alone could give him. . . . She helped to protect him from growing up.”

His lack of a university education left him, he thought, outside literary society. In September 1913 he was in France to teach English at the Berlitz School in Bordeaux. In the spring of 1914 he told his mother he had decided to become a poet. He avoided the war for a while, spending time drawing pictures of wounded soldiers he had seen at a military hospital in Bordeaux, sending them to his younger brother “to educate you to the actualities of the war.”

In October 1915 he enlisted in the military, joining the 28th Battalion of the London Regiment (Artists’ Rifles). His experiences provided the background of his poetry. In “Anthem for a Doomed Youth,” he spoke for the many: “What passing-bells for those who die like cattle? / Only the monstrous anger of the guns. / Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle / Can patter out their hasty orisons.”

Guy Cuthbertson adeptly shows Owen’s sharpness and intelligence, with a directness in his poetry that makes the reader experience the horrors of that war. The digressions into the lives of other artists and writers—Joyce, Toulouse-Lautrec, Isherwood—are not particularly relevant, but they demonstrate Cuthbertson’s intense inquiry into Owen’s life. With the arrival of the centenary of the Great War, Cuthbertson skillfully introduces new readers “to the poetry, to the young moustached face, and to the story of his life.”

Daniel P. King

Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin