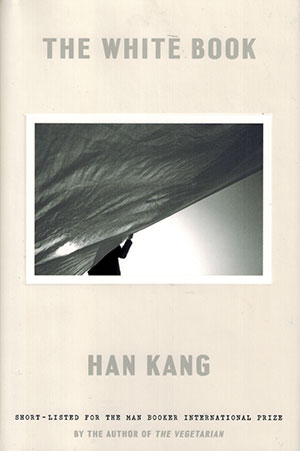

The White Book by Han Kang

New York. Hogarth. 2019. 160 pages.

New York. Hogarth. 2019. 160 pages.

Han Kang’s The White Book is a meditation on grief using a study of white objects in the author’s life to spark memories of events she did—and did not—experience, specifically the birth and deaths of her older sister (and a quickly mentioned older brother, who also succumbed to premature birth) and their mother. The book’s focus on white originates from the little that Kang—the third child of her mother but the first to live beyond a few hours—knew of her onni, or older sister. Early in the memoir, which reads more like poetic musings, Kang introduces the reader to the image that will repeat throughout the work, that her sister—born premature and dead within two hours in a remote village—had “a face as white as a crescent-moon rice cake.”

Kang’s desire to understand the death permeating the narrative of her life sends her to an unnamed albeit dreary city of which she has little knowledge—a city that feels “curiously familiar” in that it was destroyed during the World War only to be rebuilt on top of the ruins left in the war’s wake—just as she is trying to rebuild her own life on the ruins of her family’s grief. Her first task upon arriving is to repaint the apartment door, leaving it crisp and white to focus her attention on the white she plans to study while alone in her new environs—all blanketed in snow, as the reader is to assume that the clime is an element of her choice. She never admits to running away from her home, but the book pulsates with her need for distance as she tries to understand that which cannot be understood.

The book’s structure mimics her mind-set. The fragments feel more like little white islands that come together into an archipelago that can only coalesce into oneness after each island has been visited. She is simultaneously whole and fragmented, split apart by the deaths of her siblings before her birth and the ones she has physical reminders of, such as the bones of her mother burned into ash. The mother’s grief and Kang’s grief for her mother intertwine as Kang attempts to place herself in the hours of her onni’s brief life. Kang imagines opening eyes that cannot see and hearing their mother’s litany to keep the baby alive, one that the sister would not have the capacity to understand as language would have been inaccessible to her: “Don’t die. For God’s sake don’t die.”

The White Book is memoir but also memorial for all the women Kang did and did not know—and for herself and what she lost even though she never even knew what could have been.

Colleen Lutz Clemens

Kutztown University