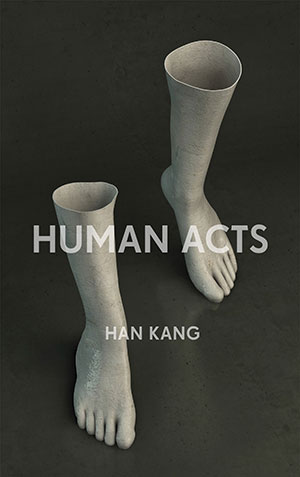

Human Acts by Han Kang

London. Portobello Books. 2016. 224 pages.

London. Portobello Books. 2016. 224 pages.

Human Acts is a very different novel from The Vegetarian, Han Kang’s first novel recently published in English to numerous accolades, including the Man Booker International Prize (see WLT, May 2016, 91). And while The Vegetarian was originally published in Korean nearly ten years ago, Human Acts is one of Kang’s most recently written books. The novel centers on the Gwangju Massacre in 1980, when the authoritarian Chun Doo-hwan ordered the military to suppress a democratic uprising in the city of Gwangju using all violent means necessary. The story is told through the point of view of multiple characters who are victims and witnesses of the massacre. Though the novel is slim and spare, like much of Kang’s work, it is epic in ambition and time scale.

The narrative focuses on the death of a middle-school boy named Dong-ho, whose story opens the novel and stays central to the narrative even after his death, as the point of view shifts each section to the many that either knew him intimately or had volunteered by his side during the massacre. His life and death become the initiating action of the story’s central narrative, which is focused less on a particular plot and more on the nature of memory, guilt, and the way that survivors memorialize and mourn what happened in Gwangju and how it continues to affect the present.

The title asks from the book’s outset, “What is a human act?” It then proceeds throughout the novel to ask rather didactic questions concerning conscience, compassion, and guilt in the face of the government machine. Many more questions frame the narrative, a lesson learned well from Anton Chekhov, who once wrote that “the role of the artist is to ask questions, not to answer them.” This is usually effective, but the sheer number of questions in the novel can be overwhelming, and the urgency of the narrative falters at such moments. Regardless, Kang is bold in her exploration of what a novel can do and be. Much as Toni Morrison does in her first novel, The Bluest Eye, Kang pushes the possibilities of the genre by moving from the first, second, and third point of view, traversing large spans of time and incorporating real documents and witness testimonies, all of which contribute to exploring the violence of man against man and the violence of the state against its people.

What follows is an epic battle of the weak against the strong. The people are helpless before the omnipresence of the state. Jin-su, a man who originally resisted the military attack alongside volunteers such as Dong-ho and later resisted military attack in the provincial office, muses that they couldn’t even lift the gun and shoot after soldiers opened fire on them. This starkly demonstrates how the innocent were brutally exterminated and how, after the survivors are imprisoned following sham trials and tortured for being enemies of the state, truth is shaped solely by the government machine. The omnipresence of violence is also counterbalanced by compassion. Dong-ho becomes a kind of abstract figure and symbol for the survivors, perhaps because he was so young and innocent when he was killed during the massacre. All who were acquainted with him remember him over the years and memorialize his sacrifice, making his absent presence central to the novel.

Though violence is vividly depicted throughout the novel, one of the few tender moments is when Dong-ho’s mother recalls him breast-feeding from her “soft right breast,” “pulling at that deformed nipple,” then later sucking his thumb until “the nail wore thin and transparent as paper.” Dong-ho’s mother’s vivid, precise description brings to life her loss and the sadness of the historical tragedy that, in a novel with breadth and scope, had felt just out of reach. Some readers of The Vegetarian will miss the fierce, taut language that visualized the world so precisely, and yet the unadorned writing seems deliberate as well as appropriate. Artistry is muted and takes a backseat to the vivid reality of Gwangju.

Krys Lee

Underwood International College, Seoul

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list

Krys Lee is the author of Drifting House and How I Became a North Korean (August 2016), both published by Viking/Penguin. She received the Rome Prize and was a finalist for the BBC International Story Prize. Her work has appeared in Granta, Narrative, the San Francisco Chronicle, Corriere della Sera, the Guardian, and others. She teaches creative writing at Underwood International College in South Korea.

Krys Lee is the author of Drifting House and How I Became a North Korean (August 2016), both published by Viking/Penguin. She received the Rome Prize and was a finalist for the BBC International Story Prize. Her work has appeared in Granta, Narrative, the San Francisco Chronicle, Corriere della Sera, the Guardian, and others. She teaches creative writing at Underwood International College in South Korea.