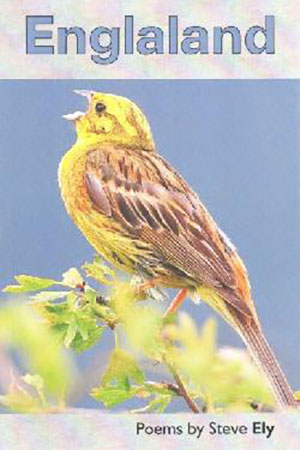

Englaland by Steve Ely

Grewelthorpe, Ripon, UK. Smokestack Books (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2015. 200 pages.

Grewelthorpe, Ripon, UK. Smokestack Books (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2015. 200 pages.

Steve Ely’s Englaland evokes postindustrial scenes that become more richly meaningful as he connects the present to the past. The first poem begins with an epigraph: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Despite the trans-Atlantic borrowing and the fact that Faulkner and Ely are each deeply rooted in different regions, the phrase is altogether apt. Ely’s verse sweeps from the tenth century to the twenty-first with an imperative sense that this England is continuously one language, one people, and one landscape.

Ely brings ancient verse forms into contemporary English poetry in a remarkably skillful way. For example, a verse in section 1 of “The Battle of Brunanburh” reads, “Sword-slit ship-man crawling in the surge, waxy as tallow; current whips him away. Dewfall, blindlight, shouts breaking like stars in the rout to the river, tumult of thundering horsethegns.” The compounding, stress pattern, and alliteration are deeply rooted in English poetry. The form is appropriate to the tenth century, certainly, but a thousand years afterward (in section 12) the form persists: “Sheffield and Hallamshire Cup, September, ’85. Away to The Gate, at Swinton. We got beat, nine-nowt. They had back-perms and their thighs glistened with oil. We had bed-hair and beer-guts.” Within this poem, raiders become trespassing fishermen, brawling mercenaries become rowdy soccer fans—part of the reader’s pleasure is to discover what century they’re in at any moment.

Englaland varies from alliterative verse to ballads, from prose poems to verse drama. “Scum of the Earth: A Play in One Act” pairs anachronistic characters Arthur Wellesley, First Duke of Wellington (1769–1852), with a living contemporary, Peter Benjamin, Lord Mandelson of Foy. Each leads an army of working-class men known only as “First Swine,” “Second Swine,” and so forth. While Wellesley urges his men to attack through nativist and nationalistic platitudes, Mendelson rallies his troops with the promises of modernity and globalization. The men are little swayed by either; they understand they’re being used. Frustrated, the lords heap abuse on their “swine” for their proletarian ways, until at last the field devolves into a mob and both lords are lynched. But it is clear to the “swine” that they have won only a temporary satisfaction.

One aspect of the work might be easy to overlook, given its rich content and skillful artistry: Englaland is fascinating to consider through the lens of ecopoetics. Designedly, the land is not mere setting or backdrop but an important character. The final poem’s eponymous yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella) lends its image to the book’s cover. “Spearhafoc” is another example. The title plays upon the bellicose phrase “spear-havoc,” but it actually means the modern sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) who speaks the poem. Norse mercenaries, medieval highwaymen, and modern outdoors enthusiasts share the protagonist’s role with the birds they watch, the fields they trespass upon, and the thousand-year-old groves on Ringstone Hill. Englaland is fertile ground for environmental literary criticism.

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University