Who Me, Postcolonial? Alain Mabanckou’s Transatlantic Exchange with James Baldwin

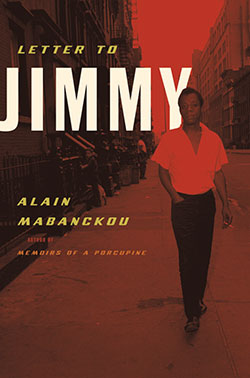

What happens when a francophone author imagines an epistolary exchange with an African American icon? In Letter to Jimmy, Alain Mabanckou offers a spectacular yet “anxious” tribute to James Baldwin as his pan-African model, literary father, and fellow expatriate.

A consensual historiography typically presents the francophone African writer as at odds with a French tradition reluctant to allow him or her unconditional access to its field, let alone include him or her in its canon. As Alain Mabanckou writes, discussing in 2011 what he considers “the strange fate of the African writer”:

For several years now, the issue of the status of the writers of Francophone sub-Saharan Africa has been much debated. These writers do indeed have a special status inasmuch as “French” writers are very rarely asked to justify their aesthetic choices or to show what their place is in French literary history and how they relate to social change in France. (75)1

Contrasting sharply with this ever-tormented quest for legitimacy within French letters, encounters with other literary traditions are usually described in more benevolent terms. One obvious example is the historical relationship to the African American canon, which is typically presented as a fundamentally hospitable contact, characterized by fluid transnational exchanges, collaborative engagements, and unequivocal patronage. Indeed, from Alan Locke’s oft-commented influence on francophone Négritude in the 1930s to the role of African American expatriates Richard Wright, James Baldwin, or Chester Himes in the second half of the twentieth century, American literary giants have been repeatedly cast—and very rightly so—in the crucial role of enabling elders to a number of young poets and novelists from the French colonial empire, including Martinique, Senegal, Guyana, Cameroun, and the Congo. However, while there is no denying the fact that black American predecessors have been and continue to be crucial for several generations of French-speaking authors, it has become a sort of topos of countless narratives that tender images of unadulterated admiration, filial deference, and literary brotherhood, leaving aside less romantic aspects such as the inevitable enmities and literary rivalries.

I want therefore to complicate this image of the “natural” and unequivocal relationship between sub-Saharan African writers and African American writers by taking as a case study a fictional dialogue between the Franco-Congolese Alain Mabanckou and his “elder” James Baldwin (1924-1987). “Baldwin, ce frère, ce père,” writes Mabanckou, professing his admiration in the pages of the Magazine Littéraire after the publication of his Lettre à Jimmy (Letter to Jimmy) with Editions Fayard in 2007.2 Letter to Jimmy is without a doubt “Alain Mabanckou’s ode to his literary hero and an effort to place Baldwin’s life in context within the greater African diaspora,” as the blurb on the English cover announces.3 In what follows, I will suggest that beyond the overt tribute—on the anniversary of Baldwin’s death in Provence twenty years earlier in 1987—the text also shows signs of a literary self-consciousness, which we might call an anxiety of (postcolonial) authorship.

By using the expression “anxiety of authorship,” I obviously wish to follow the theoretical path traced some decades ago by two important studies. The first and obvious one is Harold Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence (1973), which examines European writers’ relationship to the work of their illustrious predecessors. Bloom famously termed “anxiety of influence” a certain fear experienced by writers who are confronted with the achievements of their literary “fathers.” Writing after them, would, according to Bloom, render true originality impossible, as any successive text would appear a misinterpretation or at best a mere repetition of the masters. Bloom identified a series of possible strategies, or what he calls “revisionary ratios,” that writers have put forward in their efforts to cope with this anxiety.4 I will apply one of these strategies, apophrades, or the return of the dead, to Alain Mabanckou’s transatlantic correspondence with James Baldwin.

In speaking of “anxiety of authorship” I am also theoretically indebted to the feminist and more radical critique of canon-formation offered by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in their equally famous The Madwoman in the Attic. “That writers assimilate and then consciously or unconsciously confirm or deny the achievements of their predecessors is, of course, a central fact of literary history,” write Gilbert and Gubar, calling for a different literary history that would also account for “the tensions and anxieties and inadequacies writers feel when they confront not only the achievements of their predecessors but the traditions of genre, style and metaphor that they inherit from such ‘forefathers’” (46).5 The essentially gendered dimension of Western literary historiography was at the core of Gilbert and Gubar’s investigation, giving way to a different set of inquiries: “What does it mean,” they ask, “to be a woman writer in a culture whose fundamental definitions of literary authority are both overtly and covertly patriarchal?” (45-46).

Francophone writers are certainly not immune to this universal condition created by the desire to produce original work while coming to terms with the spectral presence of previous literary voices.

This question indeed resonates with anyone familiar with debates in francophone studies. Thus, moving to another context, I would like to investigate the issue of “anxiety of authorship” as it relates to francophone postcolonial writers. Francophone writers are certainly not immune to this universal condition created by the desire to produce original work while coming to terms with the spectral presence of previous literary voices: “To what extent is my creativity encumbered by the influence of my predecessors?” “What if my writing is merely a rewriting?” “Where exactly is my originality?” “Is this originality acceptable as literature?” “How does my writing measure up to the canon?” These could very well be questions that come to the mind of contemporary writers originally from Africa and the Caribbean who “attempt the pen” in the French language. Like any writers, they are potentially subject to these kinds of tormented speculations on their place and value on today’s literary scenes, as they find themselves having to negotiate their position with regard to Western centers and canons.

With this in mind, I would like to examine further the implications of the tribute to Baldwin at the core of Letter to Jimmy. Letter to Jimmy obviously continues a long tradition of displays of respect for great African American authors by francophone writers.6 The author of Another Country, The Fire Next Time, and Giovanni’s Room, to name just a few of his novels, Baldwin has been an inspiration in the black world for decades.7It could be that this “encounter” is a marketing coup, cashing in on the anniversary of Baldwin’s death.8 Still, one can wonder: Why “write to Baldwin” in 2007? What does the desire to “correspond” with Baldwin tell us about being a postcolonial francophone author in the twenty-first century? Why should Baldwin matter in Mabanckou’s search for auctorial singularity in French and world literature?

With this in mind, I would like to examine further the implications of the tribute to Baldwin at the core of Letter to Jimmy. Letter to Jimmy obviously continues a long tradition of displays of respect for great African American authors by francophone writers.6 The author of Another Country, The Fire Next Time, and Giovanni’s Room, to name just a few of his novels, Baldwin has been an inspiration in the black world for decades.7It could be that this “encounter” is a marketing coup, cashing in on the anniversary of Baldwin’s death.8 Still, one can wonder: Why “write to Baldwin” in 2007? What does the desire to “correspond” with Baldwin tell us about being a postcolonial francophone author in the twenty-first century? Why should Baldwin matter in Mabanckou’s search for auctorial singularity in French and world literature?

As one critic put it, one might speak of a “phénomène Mabanckou” in recent years.9 A prolific and media-savvy novelist, Alain Mabanckou started his career as a poet, publishing his first works in the Maison Rhodanienne de Poésie in 1993. He subsequently turned to the novel, beginning with his critically acclaimed Bleu blanc rouge, published by the Parisian publisher Présence Africaine in 1998. He has since consistently published with several other Parisian publishers (including Serpent à Plumes, Seuil, Gallimard, and Fayard), each successive book receiving near unanimous praise by French critics.10 Further, as an author and a professor at UCLA, Alain Mabanckou is a highly visible figure whose interventions in print and digital media are frequent, and his signing of the 2006 Littérature-monde manifesto that famously announced the “death of Francophonie” and the advent of a transnational “world literature in French” only added to this notoriety.11

Indeed, Mabanckou is no stranger to metaliterary matters. A great number of his novels interrogate what it means to write, what it means to be postcolonial. From Verre Cassé to African Psycho and Black Bazaar, his narratives appear saturated with literary references. Drawn from a wide range of traditions spanning the globe, his texts offer a truly heterogeneous display of textual references including French, African, and Caribbean. Full quotations, revisions of classic titles, allusions to archetypal characters, juxtaposed epigraphs, and even fellow writers’ interventions all contribute to the integration within the stories of a transnational and cosmopolitan library of world literature. Indeed, the deliberate heterogeneity and apparent randomness at work in his novels takes on the creative dimension of an intertextual “bazaar” where all sorts of sources mix in the most playful and unpredictable manner.12

What is at stake in Mabanckou’s imagining himself writing to Baldwin?

Letter to Jimmy follows this pattern as it is a fabulous exercise in the epistolary genre, where the temporal lag between the contemporary francophone and the North American elder allows for a multifaceted scenography, involving musings on literature, of course, but also the arts, globalization, urban life, exile, and identity politics. As many specialists of the epistolary genre remind us, the literary exchange of letters is to be understood as a mise-en-scène of communication that involves a double enunciative situation: an exchange between the letter-writer and his recipient; and an exchange between the author and his readers. Both levels are obviously intertwined here. What is at stake in Mabanckou’s imagining himself writing to Baldwin? If the letter-writing is as much about the author as it is about its imagined recipient, what does it reveal of Mabanckou’s projected posture and the message it sends to his readers?13 In addition to the choice of the epistolary genre, the use of the titular nickname “Jimmy” obviously stages a considerable degree of familiarity with the great author. Beyond the title, the address “Jimmy” appears in countless occurrences, as “Cher Jimmy” is typically used to open chapters, but also as a repeated term of endearment throughout the letter. The choice of the familiar “tu” address fulfills a similar function. It is in this “tu” that a brotherly posture takes shape, bridging the temporal as well as generational gap between the two authors.

I would argue that the epistolary genre allows Mabanckou to insert himself in Baldwin’s biography through a common “nous” that reimagines a shared black Atlantic status, setting up “Jimmy” in a multiple predecessor role as elder, fellow black writer, but also fellow French American expatriate. The latter is made clear toward the middle of the book when the author shares with Baldwin stories of contemporary France, writing, “La France, notre pays commun d’adoption” (France, our common adoptive country) (149).14 As Rokiatou Soumaré observes in her review of the book in 2015:

These flashbacks into Baldwin’s life offer Mabanckou an opportunity to reflect on contemporary France and Africa, for he draws parallels and contrasts between France’s difficulties with immigrants from former French colonies and the United States’ tradition of welcoming immigrants.15

Both France as a common adoptive country and America as shared experience thus forecast a convergence of black Atlantic trajectories between the two authors, as Letter to Jimmy allows the Franco-Congolese-American Mabanckou—who now lives in California—to situate himself within the illustrious family of African American expatriates in Paris.16

There is no doubt that Mabanckou shows himself absolutely respectful and admiring of the Great Baldwin. In the many interviews given to the French media upon publication of Letter to Jimmy, such as the one with Michele Butumay in Paroles Gelées, Mabanckou insists on his admiration for Baldwin:

Bumatay: Votre façon de vous adresser à James Baldwin en l’appelant « Jimmy » suggère des rapports familiers entre vous deux. Comment décririez-vous la relation entre vos écritures? Baldwin est-il votre « ami », « complice » ou « mentor » grâce à ses apports à votre réflexion littéraire?

Mabanckou: Je pense qu’il est tout cela. Quand on admire un écrivain il devient votre frère, votre ami, votre complice et, au-delà, votre mentor. James Baldwin est fascinant aussi bien dans son écriture que dans sa vie. (29)17

At the same time, the author of Letter to Jimmy is hardly self-effacing. Rather, the letter surreptitiously moves from the implied vertical relationship to a more lateral one, gradually substituting the genea-logical for the logical. Within the contours of a historical black Atlantic, a subtle discourse of kinship and resemblance unfolds, whereby the authoritative voice on literature and black writing becomes not so much Baldwin but Mabanckou. As Charles Green writes, “Letter to Jimmy is a tribute from one expatriate writer to another who achieved his dream of becoming ‘an honest man and a good writer.’”18 I would add that, rather than an address from a “young poet” to an established writer, Letter to Jimmy is a letter from one icon to another.

Letter to Jimmy also recasts Mabanckou in his role as literary critic. Again, the role of epistolary essayist is not a modest one. A cross between Montaigne, Montesquieu, and the Rilke of Letters to a Young Poet, Letter to Jimmy inaugurates a hybrid genre operating between scholarly norms (with its 139 footnotes) and less formal commentaries. The result is a triple intellectual relationship: Mabanckou reader of Baldwin, Mabanckou presenting Baldwin to his readers, but also, in the final analysis, Mabanckou lecturing Baldwin about France and globalization. This latter operates in an audacious reversal of paternity whereby James Baldwin ceases to be an “ancestor,” to be properly reappropriated in the fiction as “Jimmy,” a nonthreatening soul mate whose singularity mirrors Mabanckou’s rather than outshining it. Here, in contrast with earlier novels where paternal figures stand out for their dominance, this particular text ultimately abolishes hierarchies of generation. Or even reverses them, as it reinforces Mabanckou’s fame as a global black writer.19

What I see at play here is a process similar to the last of Harold Bloom’s revisionary ratios in Anxiety of Influence, namely, apophrades, or the return of the dead in which the author addresses the haunting presence of the predecessor incorporating him (it is a “him”) in a revisionary movement that reverses the power relationship between father and son. A similar bloomian reversal operates in Letter to Jimmy. As Bloom explains, in the apophrades reversal:

The mighty dead return, but they return in our colors, and speak in our voices, at least in parts, at least in moments, moments that testify to our persistence, and not to their own . . . so that the tyranny of time almost is overturned, and one can believe, for a startled moment, that they are being imitated by their ancestors.20

Ultimately, Mabanckou’s bloomian apophrades reclaims postcolonial authorship by magnanimously paying homage to the elder, while crowning the uniqueness of the contemporary narrator as privileged interlocutor. In this permutation, the “I” of the francophone postcolonial author acquires a new transatlantic preeminence as a unique cosmopolitan voice that has the capacity to subsume both experiences, peruse all libraries, and travel all territories, including Africa as the “native” land and France and America as adoptive countries. In this sense, paying tribute pays back, yielding a double literary return. On the one hand, it confirms Baldwin’s enduring iconicity in France and in the black world, twenty years after his death in 1987. On the other, it elevates Mabanckou’s own status as commentator of black experiences across time and space, now sharing a common exceptionality of talent and fame with his great predecessor.

University of Pennsylvania

Footnotes:

[1] Alain Mabanckou and Donald Nicholson-Smith, “Immigration, ‘Littérature-Monde,’ and Universality: The Strange Fate of the African Writer,” Yale French Studies 120, Francophone Sub-Saharan African Literature in Global Contexts (2011), 75–87.

[2] Le Magazine Littéraire. 2008/7 (n°477), 80.

[3] Letter to Jimmy (Soft Skull Press, 2014). Originally published as Lettre à Jimmy (Fayard, 2007).

[4] Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (Oxford University Press, 1973).

[5] Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (Yale University Press, 1979).

[6] On African writers and the legacy of African American author Chester Himes, for example, see Pim Higginson, The Noir Atlantic (Liverpool University Press, 2011).

[7] Cameroonian Simon Njami, for one, had written an extensive scholarly piece on Baldwin fifteen years earlier, in 1991. Simon Njami, James Baldwin ou le devoir de violence (Seghers, 1991).

[8] For insight onto Mabanckou’s intentions with this text, see his interview with Michelle Butumay, “La collaboration à distance: Entretien avec Alain Mabanckou,” in Paroles Gelées 25, no. 1 (2009).

[9] “Le phénomène Mabanckou,” Jeune Afrique, 11 February 2009. See also La Quinzaine littéraire.

[10] He is a prolific novelist, the author of several award-winning, including Bleu blanc rouge, Grand prix de l’Afrique noire (Présence Africaine, 1998), African Psycho (Serpent à Plumes, 2003), Verre Cassé (Seuil, 2005), Mémoires de porc-épic (Seuil, 2006), Prix Renaudot, Black Bazar (Seuil, 2009). See the author’s exhaustive Wikipedia page for a complete bibliography, including all literary awards.

[11] For a discussion with the author on the genesis, goals, forms, and appeal of his blog, see the essay “New Technologies and the Popular: Alain Mabanckou’s Blog,” Alain Mabanckou and Dominic Thomas, Research in African Literatures 39, no. 4, Positively Popular: African Culture in the Mainstream (2008), 58–71.

[12] For an exhaustive study of intertextual references in Mabanckou’s novels, see Servilien Ukize’s dissertation, “De la pratique intertextuelle dans l’œuvre romanesque d’Alain Mabanckou,” University of Western Ontario, 2013. A number of essays have also examined intertextuality in Mabanckou’s oeuvre, including Kathryn Batchelor, “Postcolonial Intertextuality and Translation Explored through the Work of Alain Mabanckou,” Intimate Enemies: Translation in Francophone Contexts (2013): 196; Pascale de Souza, “Trickster Strategies in Alain Mabanckou’s Black Bazar,” Research in African Literatures 42, no. 1 (2011): 102–19; Pierre-Yves Gallard, “Mémoire et intertextualité dans Verre Cassé d’Alain Mabanckou,” Malfini 25 (2010). See also Koffi Anyinefa’s insightful review of Black Bazar in Nouvelles Etudes Francophones 25, no. 1 (2010): 287–90.

[13] For a broader discussion of Mabanckou’s posture, see Bernard De Meyer, “Posture and Writing: The post-Renaudot Mabanckou,” Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 52, no. 1 (2015): 189–200.

[14] On representations of France in Mabanckou’s novels, see Kathryn Kleppinger’s article “New Ideas of France: The Reconceptualization of Nation-Based History and Culture in Alain Mabanckou’s Demain j’aurai vingt ans,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 17, no. 2 (2013): 220–26.

[15] Rokiatou Soumaré, review of Letter to Jimmy: On the Twentieth Anniversary of Your Death, World Literature Today 89, no. 2 (2015): 77–79 (78).

[16] For recent studies on black Paris, see Jeremy Braddock and Jonathan P. Eburne, eds., Paris, Capital of the Black Atlantic: Literature, Modernity, and Diaspora (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). For a review of recent scholarship on black Paris, see Kathryn Kleppinger’s review essay, “There’s Something about Paris,” American Literary History (2015).

[17] Michelle Butumay, “La collaboration à distance.”

[18] Charles Green, “Addressing James Baldwin,” The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 21, no. 6 (2014), 44.

[19] On Mabanckou’s fame, see Vivian Steemers’s essay, “Liberation and Commodification of a Postcolonial Author: The Case of Alain Mabanckou: Mabanckou’s Road to Fame,” Journal of the African Literature Association 8, no. 2 (2014): 195–218. On fame in a postcolonial context, see Lydie Moudileno, “Fame, Celebrity, and the Conditions of Visibility of the Postcolonial Writer,” Yale French Studies 120 (2011): 62–74.

[20] Bloom, Anxiety, 141–43.