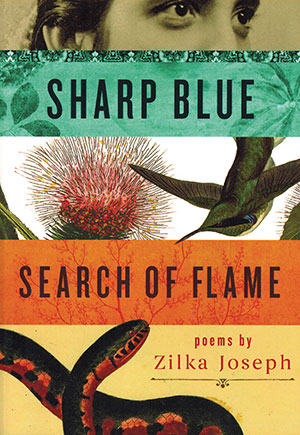

Sharp Blue Search of Flame by Zilka Joseph

Detroit. Wayne State University Press. 2016. 116 pages.

Detroit. Wayne State University Press. 2016. 116 pages.

If the American critic Stephen Burt’s precepts for reading new poetry—look for a persona and a world, not for an argument or a plot—are to be heeded, then Zilka Joseph’s first book eminently meets those criteria. In addition to a distinct persona inhabiting a world of dual cultures, Joseph also makes an argument.

Her subject matter and her language are shaped by two worlds—her Indian heritage and her residence in America—and her persona is molded by diverse influences, including Indian mythology and epic heroes, Hindu festivals, Jewish customs, growing up in Kolkata, the violence of rape and bride-burning, the experience of migration and the resulting dislocation, American folk music, and Mozart. She has a particular sensitivity to the natural world of birds, reptiles, flowers, and whales as well as the American outdoors.

Joseph has a wonderful ability to combine the concerns of one poem (“Something Falls”) to echo the contents of another one (“The Blessed”). In the first, a girl nursing a childhood crush is diagnosed with polio (“I drag my wounded body / the way I will do / for the rest of my life”), and in the second, a wounded bird is rescued and given shelter (“my wild, starved, one-legged one”).

In “Dharamsala,” a pilgrimage-trek draws in the Himalayan backdrop, steep climbs, and market-square stops and blends cozily with the intimacies of conjugal love.

“Prey” exposes the familiar, materialistic trap of a marriage starting wrong resulting in domestic violence. Joseph uses understatement to depict the woman’s predicament rather than employ a strident, angry tone. In “Havan,” she gets more daring, getting the poem’s structure to zigzag across the page to mimic the household chase as a young bride is set on fire. On the other hand, “What Burns” could have gained from further elaboration.

Less successful are her forays into Hindu mythology and her musings on goddesses, which seem to me to be assertions of female spirituality. Similarly, her attempt at creating a word-equivalent of mudras, in “The Bharat Natyam Dancer,” doesn’t entirely come off.

Where Zilka Joseph excels is in her recording of family stories; the memories are photographic in their sharpness and unflinching in their revelations. She is equally adept in her handling of form to suit the needs of each poem.

Altogether, a strong debut collection.

Saleem Peeradina

Siena Heights University