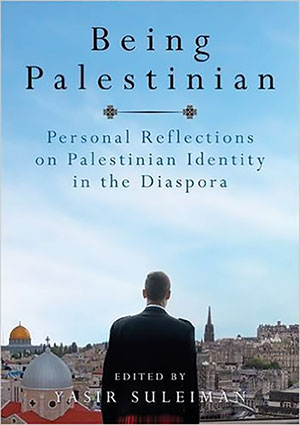

Being Palestinian: Personal Reflections on Palestinian Identity in the Diaspora

Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 2016. 370 pages.

Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 2016. 370 pages.

One hundred and two Palestinians in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States have contributed essays of about one thousand words each to this book edited by Yasir Suleiman, chair of Modern Arabic Studies and a fellow of King’s College at the University of Cambridge. Men and women, Christians and Muslims, they include well-known academics, writers, poets, and Palestinians of other interests—arranged alphabetically by name, and all introduced at the top of their essays by a brief biography and a color photograph, except one: Anonymous.

The contributors were asked to write on what it means to be Palestinian in the diaspora and to speak from the heart, avoiding politics and intellectual intrusions. Difficult as this task may appear, I believe they have succeeded—some of them having recourse to autobiographical memories and others to analysis of personal feelings; but they all spoke of the unforgettable effect on them of being forcibly dispossessed of their homes and homeland when Israel was created in 1948. Doing so, they revealed an indelible and specific Palestinian identity that, despite their dispersion in the world, has continued to be alive in the diaspora, even after they had acquired the citizenship of their host countries. This identity is not exactly the same for all Palestinians, but there are sufficient common elements of it for them all to make it a mark of belonging. First among those, of course, is language—the spoken Arabic language of Palestine, with its village and city varieties and its special cadences. But there are other elements that each contributor to the volume spoke of, even if language was not mentioned or was taken for granted, and they are mainly cultural.

The material culture of Palestine is reflected quite strongly in many essays of the book, including food, even particular dishes like mujaddara (rice and lentils) or dips like zayt u za‘tar (olive oil and powdered thyme), but it is also reflected in dress embroidery, in music and song, and in dance—especially dabkeh, a group folk dance characterized by exuberant joy in social celebrations and sometimes with political implications.

Existential experiences, however, are most pertinent for most contributors, as they report their personal feelings on contemporary Palestinian conditions of injustice, suffering, struggle for survival, resilience, and continuing restlessness. One contributor says appositely, “I am a Palestinian rock that is still rolling to its final resting place.” There is hope, always hope, as an element of Palestinian identity.

Editor Suleiman, himself a Palestinian, is to be congratulated on this volume of personal reflections collected from Palestinians in the shatat (the diaspora), for the use of all those who may be curious and interested to learn more about his people who, in the West especially, are unfairly maligned by their enemies.

Issa J. Boullata

McGill University, Montreal