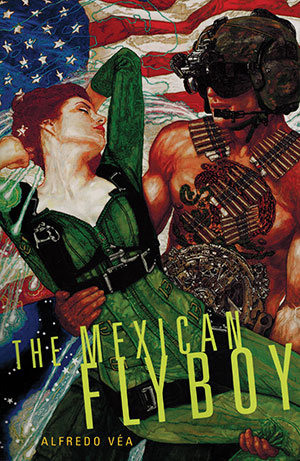

The Mexican Flyboy by Alfredo Véa

Norman, Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. 2016. 338 pages.

Norman, Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. 2016. 338 pages.

The Mexican Flyboy reads like a surrealist dream: it is a fairy tale for adults, a novel where clairvoyant superheroes (Mandrake the Magician) and historical figures (Joan of Arc, Jesse Washington, and Ethel Rosenberg, among others) are brought to life by an incantatory language that animates and reenacts a history of unparalleled horrors, unrelenting fanaticism, and crowd complicity.

The lead character is Simon Vegas, a university professor and Vietnam veteran who takes wing on his Antikythera device to each place and moment of execution of persons falsely or maliciously accused in the past, gently transporting the suffering and maimed to a retirement resort in Boca Raton, Florida. A vast mural with satire and irony as the dominant palette, The Mexican Flyboy sketches the life of a skydiver by the name of Sophia Hanlon and reiterates the traumatic memories of her free-falling death in a California vineyard that haunt Simon Vegas most of his life. From this incident, the novel unfolds into a collage of interrelated stories: a bildungsroman, a war narrative, the detailed record of the gestation and birth of a baby girl, and a critique of the mob behavior of peoples, from ancient times to recent US history.

In Alfredo Véa’s previous novels, language is vigorously raised beyond the story level, with an emphasis on style, ingenious storytelling (in the tradition of Don Quixote), and on details pertaining to the novel’s organic form. In The Mexican Flyboy, the verbal craft reaches a higher spiraling point with passages suggestive of poetic ambiguity (“Slip a modest flurry into a swelling bodice of billowing curtains, and men will see angels”). In the narrative, an expressiveness of a higher order engages the perplexed reader in a play of mixed genres—novel, poetry, essay, autobiography—that ambitiously expand the limits of representation. Alternate realities and multiple vantage points thus constitute the novel’s conceptual core, projecting into the field of our reading eyes a virtual world where characters interact across time and space and where the Antikythera device functions as a rhetorical figure for “time travel” into the past, therefore as the metaphor of our repressed memories and the world’s historical unconscious.

Véa’s inventive will is biblical but with deep roots in ancient Mexico. In the novel’s prologue the Word is the breath and spirit of creation, with the entire novel bound into a desired totality where poetry and an array of gusts and gales herald the incoming Toltec god of wind: Ehecatl Quetzalcóatl, the inventor of the Mesoamerican calendar, creator of humanity, and a culture hero with an avowed aversion to human sacrifice. Véa chisels his novel with the glyphs and geometric artistry engraved in the Aztec Sun Stone, insinuating in its calendrical wheels a twinning or symmetrical relation with the brass knobs and wheels in the Antikythera device that calibrate the year, the day, and hour of human suffering and absolution.

In the novel’s epilogue the theme is Hebrew history, with Hitler’s Germany and the Jewish Holocaust as the time and place where humanity’s hatreds and horrors culminate. Ezequiel, Simon’s friend, inherits the Antikythera device, travels back to the Nazi concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, and transports a budding Annelies Marie Frank to Boca Raton as the novel’s last deliverance. In this closing section of the novel, a triad of artists, creators, and writers triggers the reader’s epiphany: Ehecatl, Elohim, and Anne Frank call on us to remember, and to name the past for what it really was.

Roberto Cantú

California State University, Los Angeles