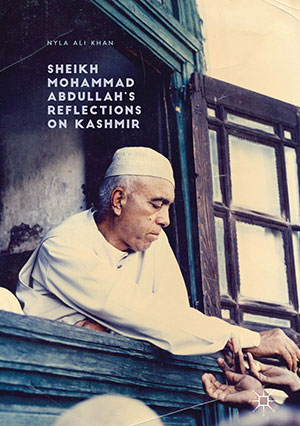

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s Reflections on Kashmir by Nyla Ali Khan

New York. Palgrave Macmillan. 2018. 215 pages.

New York. Palgrave Macmillan. 2018. 215 pages.

In the insightful introduction to her latest book, Nyla Ali Khan remarks that the “primary readership will comprise students and scholars of South Asia.” This academic subset should not be thus circumscribed. There is much here that any citizen of any state could absorb as a series of object lessons in the nature and propagation of a democracy that deserves to endure.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, even after his 1982 passing, remains a towering inspirational figure in Kashmir and a nemesis to authoritarians in both India and Pakistan. Born into a middle-class family in 1905, he became an early leader of a liberal-progressive movement to free the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir of its monarchic repressions long before it was carved in half between India and Pakistan.

The personal history of this seminal force for Kashmiri liberation is well documented elsewhere; this book contains a compendium of Abdullah’s letters, lectures, and press articles, which carefully document his laws-into-sausages struggle to achieve a free, independent Kashmir based on pluralism, a rejection of the religious split between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs that ultimately truncated South Asia into endlessly combative, nationalistic, and regressive regimes.

Often, Barack Obama being an example, a leader with progressive principles who works tirelessly to achieve compromises to improve conditions, while avoiding backlash wars, is destined to be reviled in doctrinaire quarters as a centrist, a neoliberal, or even a traitor to certain principles. Ideological purists will never fail to find some fault in those leaders tasked on the ground with making democracy work in a world where political divisiveness is as rampant as domestic conflict and divorce. Both in Khan’s insightful introduction and concluding remarks, and in Sheikh Abdullah’s own words, it is clear that he was determined never to sell out any constituents and always to keep their true—only apparently disparate—interests in tandem.

Whereas we yet have no account of Obama’s struggles in steering a snaking course for America’s spaceship of state, reading this book and its compendium of Sheikh Abdullah’s resonant, unflagging, and articulate pursuit of Kashmiri welfare would perhaps enlighten those who delude themselves into thinking that achieving freedom and a vibrant democracy means hacking a straight line through the tangled jungle of competing interests and egos that is real politics. Abdullah struggled for real accord between all religious, ethnic, and political groups and was rewarded with long years in prison followed by roller-coaster years as Jammu and Kashmir’s prime minister and chief minister, and throughout his life he enjoyed the adulation of the ordinary people whose cause he adopted. Abdullah’s path thus provides a stellar analog to Nelson Mandela’s. Both negotiated without bitterness with those who had incarcerated them to further their just aspirations.

Sheikh Abdullah never focused on enemies, but always on Kashmiri agency. This book is an intuitive primer in democracy for anyone who would take a practical, holistic view of the democratic enterprise.

Jim Drummond

Round Rock, Texas