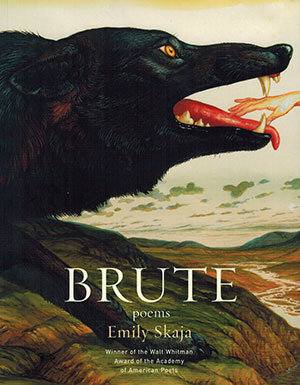

Brute: Poems by Emily Skaja

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2019. 72 pages.

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2019. 72 pages.

Much of the narrative arc—and indeed art—of Emily Skaja’s debut collection, Brute, is marked in the first poem of the book. There is skillful sound-play coupled with daring metaphors to revisit for days. And though we learn something of the beginning, middle, and end of this story of abuse and self-determination, the ominous last line of “My History As” is a reminder that escape is hardly ever a straight line: “I learned to counter like a torn edge / frayed from the damp. That’s how I left it. // Leaving the river, leaving / wet tracks arrowed in the brush.”

Frayed, leading, necessarily incomplete; in form a number of the poems seem to end like this, circling back the way predatory birds and abusive relationships do. The section of the book entitled “Circle” does exactly that after the troubled but empowered section “Girl Saints.” It is here in the third epigraph that we discover the origin of the book’s title—Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”—and, in “Four Hawks,” are reminded of the torturous work that must be undertaken to mentally escape abuse even after one has physically escaped: “why // am I the chased thing horrified / to overtake myself in the brush.”

There are a number of elegies threaded through the work that lend a certain softness to the narrative lace, like tree bark in the rain or bodies in the earth. At other times, the elegies move at a clip that outpaces their strange and unbridled language; the form itself a metaphor for the uncomfortableness of grief and inheritance that we try desperately and failingly to outrun.

Love and violence; cartography and the damages of water; “Small witchery,” in the face of a history that remains unrepentant of its sins against women and girls. These themes are mapped in repetition and layer, often woven into perilously shared spaces. “We bled on our white clothes – we bore them redly // to the table. Our fathers said Tell me, will you ever // feed me something that isn’t your own trouble? / We cast away stones. There was room at the inn. // There was time to be floated as witches.”

Chosen by Joy Harjo as the 2018 Walt Whitman Award winner, the book is shaped by its radical honesty and a sharply honed craft. Its story arrives at no easy conclusions, with the closest thing to clarity coming in the final section, when the book is at its most dreamlike: “Soon we were eating peonies & lilacs with bees inside / All these marriages had come out to watch me deliver my speech / I filled my mouth with bees I tried to speak through the bees / Everyone if we’re going to talk about love please we have to talk about violence / I was stung my tongue swelled I was spitting crushed bees / A special crew came to sweep them up before anyone could see.”

Within these lines the surreal provides cover, protection as we near a certain disquieting truth: that the spectrum of violence—physical, emotional, generational—is often entangled with love in ways not easily swallowed. So unlike the champagne, the buttercream roses, and yet it is common practice here for the bride and groom to carefully cut the cake, turn joyfully to each other, and send their frosting-filled fists into each other’s faces.

Bailey Hoffner

University of Oklahoma