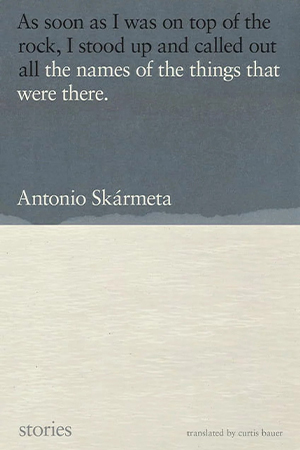

The Names of the Things That Were There by Antonio Skármeta

New York. Other Press. 2023. 352 pages.

New York. Other Press. 2023. 352 pages.

The thirteen exemplary character-driven stories in Chilean author Antonio Skármeta’s The Names of the Things That Were There, curated by Juan Villoro and translated by Curtis Bauer, transform personal experiences into flights of the imagination.

Skármeta (b. 1940) is probably best known as the writer of Burning Patience (1987), aka The Postman (1985), a novel adapted into the 1994 Oscar-winning film Il Postino. His play El plebiscito was the source of the Oscar nominated No (2012). In Villoro’s foreword, he refers to Skármeta as a “man of principles.” He says the short stories, beginning in 1967, “tackle the uncanniness of literary initiation” with two “fundamental stylistic techniques”: “rapid plots that [lead] to an inevitable denouement” and “lyrical prose [that gives] the story above all else an opportunity for metaphors to reach hallucinatory proportions.” These are perfected by an obsession with the “art of beginning” and fulfilled with the “crisp precision of an arrow.”

These distinctive qualities are immediately evident in the opening selection, “The Young Man with a Story.” In metafictive fashion, Skármeta uses his own life as subject matter. About halfway through the narrative, the twenty-year-old narrator, swimming naked in the sea, baptizes himself Antonio. At the end of his third university year, he has isolated himself in an abandoned railway car on a Chilean beach. There, seeking the meditative solitude of silence, he has something of an Adamic experience when he climbs a rock and “called out the names of the things that were there . . . repeating the ones I liked best such as mountains, shore, seagull, pelican, truth, and others like that.”

His observations of nature morph into Skármeta’s precise descriptive language: “I watched the pelicans’ wings flapping heavily, hovering over an area of water that seemed to be teeming with sardines, and I saw them swoop down suddenly, dive into the sea, and emerge into the air dripping with the fish clutched tightly in their beaks. . . . I also spotted other, smaller birds cutting through the air . . . their entire movement harmonious . . . dividing the sun, dividing it into hundreds of little suns . . . carrying its glow on their beak.” The narrator identifies with the birds, seeing himself as “Space,” wanting to be “preserved, held in warranty, inviolable.” Part of that preservation is the recognition that “naked as the birds“ and “free of all restraints,” he could “lose consciousness of everything around [him]” and succumb to “the story [he] was going to write that night.” He has transcended life events, transmogrifying into his own creation.

In other stories, Skármeta develops strong, well-defined protagonists that expose family trauma when a child is leaving home to go abroad (“First Year, Elementary”); when the fulcrum of “Basketball” is the perspective for the passions of writing, music, film, and sex; when a grandmother breaks a sugar bowl, inciting a permanent domestic schism with in-laws (“Fish”); when students are fighting for their lives or fighting the political system in the context of body shaming (“Ballad for a Fat Man”); or when a melancholy writer immigrates to Paris attempting to “assuage [his] sudden depression” (“Borges”).

Skármeta’s provocative fictions in The Names of the Things That Were There enhance his own life, delve into the souls of others, and render his subjects and themes universal.

Robert Allen Papinchak

Valley Village, California