Writer / Woman: The 2024 Neustadt Prize Lecture

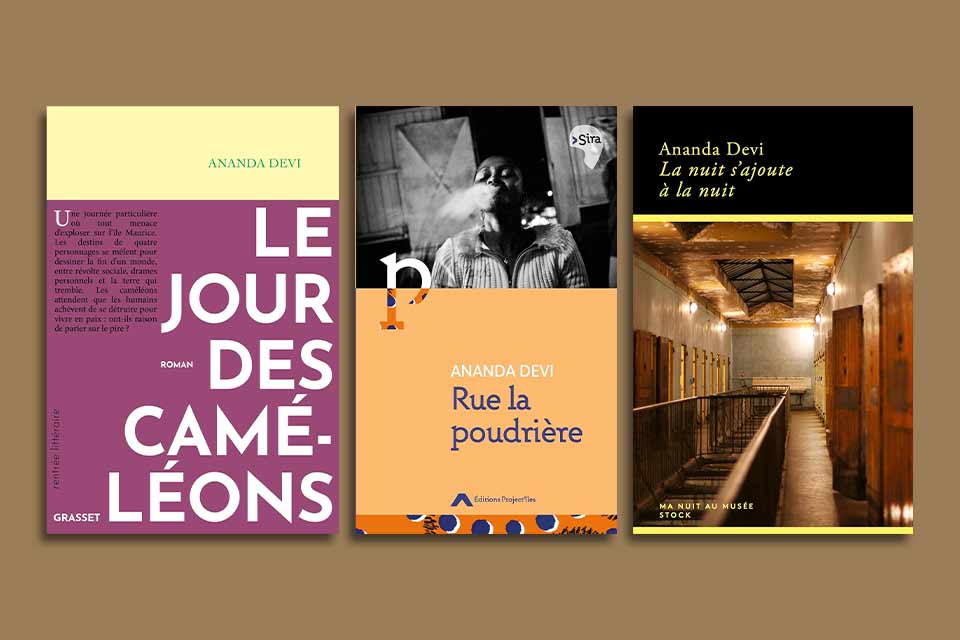

It is perhaps not a coincidence—or else it is a very felicitous one—that, in the very same month of my receiving the Neustadt Prize, my first and last books came out together in France. My first novel, Rue la Poudrière (Poudrière road), written in 1984, was republished in a new format. My last book, La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit (Night prolongs the night), is a nonfiction book forming part of a series published by Éditions Stock.

Forty years and twenty-eight books separate the two. What differences were there between these two books, forty years apart?

Rue la Poudrière is about a young Mauritian Creole prostitute living in Port-Louis in the late 1970s. After Mauritius gained its independence, its economy was solely based on the cultivation of sugarcane (an inheritance of colonialism and slavery). It was struggling to survive. Many people lived on the very edge of destitution. Many felt that they had been forsaken on the road to development, that they were neither heard nor seen.

I chose to put myself in the mind and body of this young woman, who, at the start of the novel, is running. Running where? Away from or toward something or someone? This is unclear. We are immediately adrift in the turmoil of her thoughts, in a stream-of-consciousness narrative, both harsh and poetic. Her parents, Marie and Edouard, are both larger-than-life characters, and together with Mallacre, the pimp, create a monstrous trinity reigning over the destiny of Paule, the narrator, whose tragic path is announced from the beginning. It is a relentlessly dark novel, suffused with what seems to me today to be an excessive pessimism for the times: no light in the hell of Port-Louis, the capital of Mauritius, where the novel is set. Indeed, rereading it for this new edition, I saw that, despite the reality of these human tragedies, the novel belongs to the universe of myths, where the protagonists have to go from one ordeal to another as if to test their very essence, their courage, their resilience. Port-Louis is more akin to the kind of inferno that Dante describes than to the capital of a country slowly emerging from centuries of colonial rule. I am astounded to realize that I was writing it in the year when my second son was born. I wonder how I could, at twenty-seven, delve so deeply into the despair of my narrator with a newborn baby in my arms. I think the writerly persona kept herself well apart from the womanly persona. There was a nonporous barrier between the two.

Here is a small extract I translated from the French:

When Port-Louis vibrates with this primeval rage, with the screams of men, an inhuman creature exhumed from the scrapyards, when the city shakes with the force of its subterranean rebellion, I am the one who embodies most closely its bitterness for having been traded for all kinds of greed. Whether it be the industrialist who contemplates his empire from the safety of the lair that separates him from humankind, or Mallacre, who trades in the bodies and souls of human beings, they have all sliced up the city according to their desires, transformed it into a spiderweb that awaits the next insect, already half-dead, hanging on to the branching traceries. How much time does a city need to accomplish its own disintegration?

My latest book, La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit, is both a similar and different beast. It is certainly a work of maturity. The writer and the woman, here, are brought together and seem to have become a unified whole, more so than in any of my other books. Since it is not a work of fiction, it is a text where the “I” coincides with my own self, and is able to express both a profound sadness about the subject matter and the world we live in, and to find some kind of hope in the courage of real people. It is also a book that is not fed by rage and fury, as Rue la Poudrière was, but by a deep-seated melancholy that is perhaps closer to who I am now.

La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit is fed by a deep-seated melancholy that is perhaps closer to who I am now.

It is about a Second World War memorial in Lyon, France, that had originally been a prison, the Montluc Prison, built in 1921. French resistance fighters were incarcerated here, as well as thousands of Jews (including forty-four children) prior to being shot or sent to the concentration camps. After the liberation, under the French, it was the German soldiers and French collaborators’ turn to be incarcerated before their trials. In the 1950s, French communists were imprisoned for protesting against the Indo-China War. Yet later, it was the turn of Algerian resistance fighters, who fought in the Algerian war of independence; eleven Algerian prisoners were guillotined in this very prison. Montluc became afterward a common-law prison, and the women’s wing was permanently closed in 2009. In a single place, in the very center of Lyon, almost a century of history had passed through, leaving its marks, its wounds, its tragic memories in the seeping walls—proof, if need be, of the criminal forgetfulness of humankind.

But as I spent one night alone in the prison, the resistance fighters, whether French or Algerian, began to speak to me. I felt that I was touching a small part of their turmoil and horror but also the light that arose from their courage, their belief in humanity, their refusal to compromise with the dominant power, their readiness to undergo the most horrendous tortures and even death rather than give up on their beliefs.

Addressing René Leynaud, a poet who was executed by the Germans when he wasn’t yet thirty-three years old, I tell him this:

I can only offer you one night. A ridiculous gift. But I try to instill into it everything that I am: this empathy that has so often caused me pain but has also given me the deepest of intuitions, it leads me to you, inside you, and I touch these walls that you have touched, I raise my eyes toward the narrow rectangle through which drifts a ghostly light, I sit on this floor where you lay down, and I try, just for one moment, to be with you. Inside your suffering, your fear, your regrets, your love, and this crazy hope that still resists, despite everything—our strength, our curse. So that, just for this short moment, René, you keep on living in my breast. After all, this is what you once wrote: Just allow, allow this lad to live, so slow his time, and death ensues. I am no longer living, save within your breast.

While I was writing this book, the echoes of the world surrounded me. I was writing about different forms of resistance, different forms of barbarity. And this is what I was hearing, as if the deaths going on in the world were bleeding into my book. Toward the end, I was filled with a kind of desolation. I didn’t know how to finish the book. Which shows in the afterword, where I wrote:

What I have just written isn’t over. I cannot end it. I do not want to end it. It will never end. It can never end. As long as we don’t end it, we humans. Oh, let’s just end it all.

What can I make them say, they, there, in their ruins, in the dying day? When their eyes only receive cascading rubble? What book can be filled with so much pain?

Between these two books, I am still saying more or less the same thing. What I learned in the meantime is the art of saying more with less.

So, between these two books, I am still saying more or less the same thing. What I learned in the meantime is the art of saying more with less. No need for an accumulation of adjectives, of adverbs, of endless descriptions. I have learned to be spare. To make each word count. For those who want to write, I always say the same thing: you can pour everything into the first draft, the most passionate, perhaps the most true. But afterward, the craft comes in: reading each sentence and asking yourself whether it is there for a reason.

A common denominator between all my books is the intensity with which each text, whether it is a novel, a short story, a series of poems, or a nonfiction book, emerges. This intensity, I would almost say this haunting, is essential for me to be able to sustain the writing, especially of novels, over the long haul . . .

A case in point is Le sari vert (The green sari): I have always said this was the book I was meant to write. Perhaps the reason why I had to write. After writing it, I actually thought for a while that I wouldn’t be able to write anything else.

The origin of this story goes back to when I was around ten years old and heard it from my mother. This is what I wrote in Deux malles et une marmite (Two trunks and a pot), a book about writing where I revisited this text, addressing myself to my younger self, the “you” in the following passage:

On that day of the absent cyclone, whispered words would be the tempest that would shake the foundations of our family. You knew that your mother had always been sad, but the reason was unknown. From that day onward, you would know the reason, the source, the origin of her pain, if ever there can be an origin of pain in this long chain of annihilation that are families.

A few sentences, a few words, and an image. She tells you about a dead woman. The one without a first name, without a face, without a tomb. She tells you about an erasure.

The image that will be branded onto your memory, and will lead you toward the darkest of hauntings.

They were not words, it was something torn from her, as when someone spits blood when coughing or regurgitates bits of lungs when they can no longer breathe.

The day of the absent cyclone, a woman will be turned into a statue by a pot of boiling rice thrown over her; she will invade your mind and your body.

I heard this story when I was a child. About a woman turned into a statue of grief and pain by boiling rice thrown over her. I knew I would write that story one day. Once I started writing novels and being published, I kept thinking about it. It took me three attempts over a span of fifteen years.

The story is about an eighty-year-old man, dying of some disease, who comes to his daughter’s house to be cared for. His adult granddaughter is also there. Both of the women are convinced that the old man is responsible for the death of his wife when she was just twenty-two. They want him to tell them what really happened. The daughter, Kitty, is under the sway of her father, caught in a love-hate relationship that she cannot get out of. The granddaughter, Mallika, only wants revenge and finds a perverse joy in telling her grandfather that she loves a woman and how they pleasure each other. But the novel is told in the first person by the old man himself, who used to be a medical doctor. And what we read and hear is his conviction of his power, even as he is dying: he calls himself Dokter-Dieu, Doctor-God, and gives full vent to his misogyny. He despises women. He justifies the violence against his young wife by saying that it was an act of love.

For the entire time of writing, I was in his head. I heard his sarcastic laughter and his disparaging comments. I was him. And I enjoyed it. I actually thought it was a funny novel. Yet when it came out, some readers said it was the most violent novel they had ever read. It took me fifteen years to find the way in. The way in was by letting him tell his story. I felt afterward that I had created the ultimate monster. The one with no remorse, no regret, no questioning of self.

I realized then that this exploration of violence was a constant in all my books. Where does it come from? How does the perpetrator justify it? How is choice between committing a violent act and turning away from it determined by our individuality? But then, how do we explain the spirit of the horde, of the pack, that leads ordinary people to commit atrocities, as with slavery, with the Shoah, with the Rwandan genocide, and the terrible acts being committed today under our passive eyes? Is this the result of our larger, specialized brains?

In my latest novel, Le jour des caméléons (The day of the chameleons), published in 2023, I imagine a kind of apocalypse hitting the island of Mauritius in a near-future brought about by the actions of men.

This apocalypse, which, according to the novel, was breeding for centuries, is brought on by four catalysts: Nandini, a fifty-year-old woman, wife of a judge, living a kind of superficially perfect life, suddenly decides, one day, precisely that day, to drop everything and leave without knowing where she is going, since her life has no meaning; René, a man in his forties, a man who feels useless and has no reason to get up in the morning, must, that day, take his beloved niece Sara to school; Sara herself, ten years old, intuitive, worried, luminous, decides, on that day, to put on a white dress that will seem like a fatality; and finally, Zigzig, a small-time crook from Baie du Tombeau, leader of a gang, will, on that day, decide to exert his revenge on an enemy gang that wants to seize his territory. Their fortuitous meeting, on an ill-famed beach of Baie du Tombeau, will turn explosive and sweep through the entire island. Meanwhile, the silent chameleons wait for their day of triumph to come, when men will have destroyed themselves and they will inhabit the island with reverence and respect.

Between them all, who are the heroes? Who are the monsters? They are all ambiguous, flawed. And their decisions will radically change the image we have of them as the story progresses.

This novel could be described as a work of anticipation, a classical tragedy, an ecological fable, and a thriller.

I was not only writing about my country but also about the world. For all the issues addressed in the novel are the same everywhere. Have we reached a point of no return? I ask. Maybe not. But there is not much time left.

Delving into these hearts of darkness allows me to look upon people and society once they are devoid of the masks that distort our understanding.

Delving into these hearts of darkness, to borrow a well-known title—but not in a way that ostensibly opposes good and evil, heroes and monsters, the right way and the wrong way—allows me to look upon people and society once they are devoid of the masks that distort our understanding. As a writer, my job is to lead my readers to ask their own questions and try to find answers that are not spoon-fed to them from outside but come from their own selves. People are not black and white. They are of all shades of gray. We are all complex and ambiguous, capable of the best and the worst, and I do believe that literature is the place where this complexity and ambiguity can be fully explored.

I know that writers cannot really change the world, but I believe they do have their role to play in providing a different worldview, many different worldviews, and in offering a balanced voice amidst the cacophony of voices all too ready to present fallacies as facts, to judge without knowledge, and to condemn rather than understand.

After five decades of utter dedication to writing, it is a precious consolation.

Norman, Oklahoma

October 21, 2024