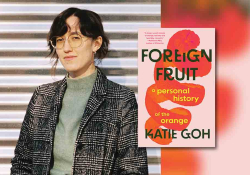

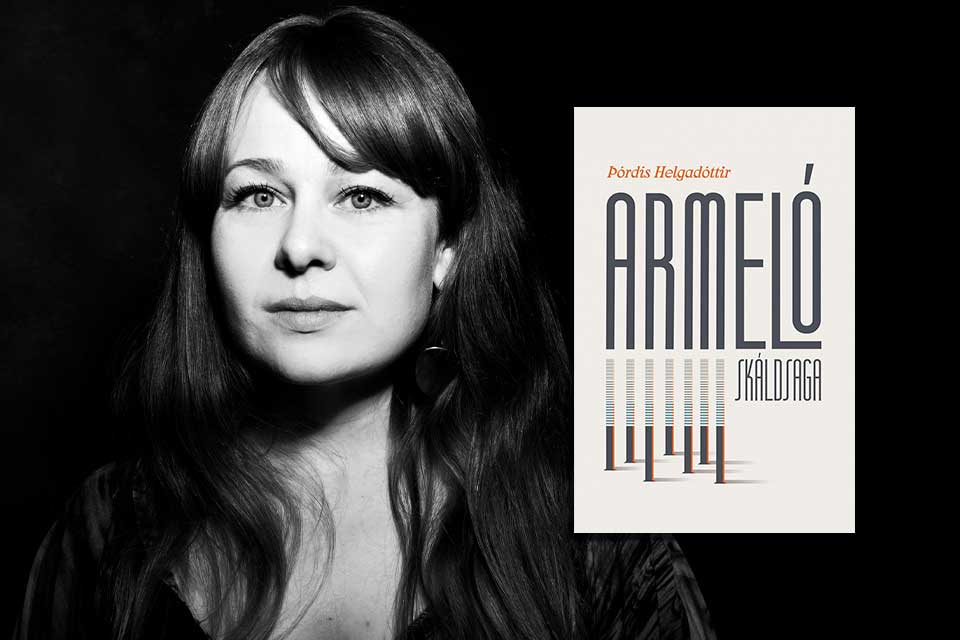

“Literature Is Iceland’s Cultural Legacy”: A Conversation with Thórdís Helgadóttir

Thórdís Helgadóttir is an Icelandic poet, playwright, novelist, and short-story writer. Her work has earned the prestigious Ljóðstafur Jóns úr Vör poetry prize and a nomination for the Icelandic Literary Prize—the highest honor in Icelandic literature—among other accolades. Her debut novel, Armelo (2023), a strange and wondrous antipilgrimage through old Europe, garnered high critical acclaim and cemented her reputation as one of the most original and exciting voices on the Icelandic literary scene. Her theatrical work has been staged at the City Theatre of Reykjavík, where she was the 2020 playwright-in-residence. Helgadóttir has long been deeply involved in local literary life in Iceland through her work as a writer, editor, teacher, organizer of literary events, and member of the writers’ collective Impostor Poets. She has an MFA in creative writing and studied philosophy at the graduate level.

Adam Goldwyn: We’ve known each other about fifteen years, but all of your work is in Icelandic and I have only read the small fraction available in translation. Can you tell us a bit about who you are as a writer and about your work as a novelist, poet, and playwright? Some of your major works, or works of which you are most proud?

Thórdís Helgadóttir: Well, I can happily report that more translations are in the works, so stay tuned—you will be able to read more soon!

There came a shift in my career last year, when Armelo was published and I finally became a novelist. At that point I had already been writing and publishing books for years, getting good reviews and even winning awards. But a novel is taken more seriously. It is, for better or worse, the dominant form of literature today. And around the world, publishers are much more interested in translating novels than poetry or short stories, which I think is a shame.

As a writer I have always found myself jumping from one project to the next, switching forms and trying out new things, almost compulsively. I greatly admire writers who seem to plan their work more methodically. This restlessness used to be a source of embarrassment for me, until people started to compliment me on my range and versatility. There is a David Bowie quote I have taken to heart: “If you feel safe in the area you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area. Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.”

Because of this inefficiency, publishing an almost 400-page novel felt like a great accomplishment. Staying committed to a novel is an endurance test, but oddly it left me hungry for more, like completing a marathon or having a baby—you want to go again! There are so many things I can’t wait to try in a novel, so many delicious possibilities.

Poetry requires the deepest level of concentration for me. I find writing poetry to be hard but uniquely rewarding work. As a reader of poetry, I feel the same way. I don’t mind working for my reward.

I like to think about what kind of contract I am entering into with the reader. With a novel, you are asking the reader for a considerable chunk of their time, a day maybe, that they could be spending walking in the woods or building a maze for their kids’ hamster, for example. You have to give them something meaty in return. And you cannot expect them to labor too hard, at least not the whole time. With poetry, you are asking for their undivided, concentrated attention, but only for a couple of minutes.

Short stories are a joy to write—and read! These are my space for experimentation, play, even gimmicks. The short story says to the reader: “Hey, check this out!” and in return you owe them something neat, a cool idea, a satisfying little morsel. I think the short story is maybe the perfect unit of fiction, like the three-minute pop song. I remain baffled as to why the novel remains the dominant form and not the short story, especially now that our attention seems permanently splintered.

As for the theater—the theater is impossible, like drawing with your nondominant hand. I’ll get back to you when I figure out how to really write for the theater!

Now, as it turns out, the same themes and obsessions keep cropping up across forms and media. I am always amazed to find that there really is an authorial voice that unites all my work, to the point that readers report being able to identify me as the author without being told. I keep coming back to the natural world—animals, and humans as animals—the strange thing that is the human sense of self, as well as apocalypses in one form or another. There is black humor, big ideas, existential questions. Above all, the work has to be exciting. Quite apart from the literary quality of the work, I feel I also owe my readers a great ride.

Goldwyn: We’ve met in Iceland twice, first in 2009 and again in summer 2024, and both times we went to Thingvellir National Park—the site of the first Icelandic parliament, which was established in the Middle Ages. Thingvellir is an important site for some of the earliest Icelandic literary production and performance, a geological wonder where the continental drift between the North American and Eurasian plates is visible, and now one of the most visited sites in Iceland by international tourists working their way through “the Golden Circle.” It’s also a productive place for thinking about some of the questions that interest me—questions about your work in particular and about Icelandic and global literature more broadly, questions of the local and the global, of literary history and tradition, on one hand, and of linguistic innovation and experimentation on the other. So my questions are: How do you conceive of your work (if at all) within the deep history of Icelandic literature, and how do you balance that with the contemporary, cosmopolitan, globalized environment in which you live and write? Are you more influenced by Icelandic writers or global writers, and are there any who were particularly influential?

Helgadóttir: In a way, literature is Iceland’s cultural legacy. As a visitor, you experience nature—the stark, sublime wilderness of the land—but in terms of historical remains, you will not find all that much. No castles or old cities, very few buildings or monuments, even visual works of art. This makes sense when you remember that throughout our history we have been, for the most part, a tiny, dirt-poor population, geographically remote, with very few natural resources.

The flip side of our isolation is that we remained relatively free from outside influence. There wasn’t much commerce. Empires didn’t spend much time trying to conquer this particular patch of land. So, famously, the Icelandic language remained remarkably unchanged for a millennium.

The sagas, these extraordinary works of literature, were preserved, partly as a reminder of our nation’s perceived former glory. On farms, stories and poetry would be recited to everyone, every night. Composition was for a long time a kind of competitive sport. In Halldór Laxness’s Independent People,1 while the dirt farmer is toiling alone in his fields, he is also crafting incredibly technically elaborate stanzas in his head—which he then casually drops when he finally sees his neighbors weeks later, impressing everyone.

So even now, I feel that being an Icelandic writer really is something quite special, even after our society has been completely transformed. In the sagas, the most prestigious professions were warrior and poet. Let’s see how it will be in another thousand years.

Goldwyn: Speaking of what the Icelandic language will be like in a thousand years, the internet tells me that there are currently between 300,000 and 400,000 speakers of Icelandic, almost all of whom live in Iceland. You write in Icelandic while also being fluent in English. Your children are both fluent in English as well; like other Icelandic youth, they speak both Icelandic and English among themselves in school. They live in a digital world that is predominantly in English and grow up on English-language television, films, music, and pop culture. (Your daughter told me she learned English watching Barbie YouTube videos.)

Even traveling around Iceland, I noticed that the linguistic landscape has a lot of English alongside Icelandic: restaurant names, billboards, street signs. Has that linguistic situation changed since you were their age? Do you worry about the survival of Icelandic as a living language of daily speech, or fear that your children or subsequent generations of Icelanders might lose their proficiency in Icelandic—and along with it, something important to them? Or, to put it another way, do you write in Icelandic for purely personal reasons of authenticity of self-expression, or is there a political statement in there as well? Do you see your writing in Icelandic as part of a resistance to English (and US cultural hegemony) and the globalization of Iceland, or do you embrace it as part of the natural evolution of global Englishes and the future of Icelandic culture?

Helgadóttir: Measured by the number of speakers, Icelandic is by definition an endangered language. Fortunately, by other metrics, it is doing quite well. For the reasons I just explained, abandoning our language doesn’t really occur to Icelanders as an option. The loss would be unimaginable.

We have been aware of this vulnerability for a long time and have adopted various policies and norms to combat it. In an interesting move last year, the government made a deal with OpenAI to train ChatGPT-4 in Icelandic, as an effort to preserve the language in the digital age. (I admit to having quite mixed emotions about this.) Monetary support to writers and publishers is another such policy. We could be doing better, of course. The much deeper problem, in my opinion, is the value system of late-stage capitalism, with its deep disdain for culture and the humanities, which permeates every facet of society.

The much deeper problem is the value system of late-stage capitalism, with its deep disdain for culture and the humanities.

Fluency is a funny thing. Icelanders have been shown to grossly overestimate their English proficiency, which is deceptively superficial and context-dependent. If we were to suddenly lose Icelandic, we would be stilted, half-speechless for at least a generation. Likewise, it has never really occurred to me, or any writer I know, to write in a language other than Icelandic for an Icelandic audience. I suppose that is a sort of healthy vital sign.

Even with the very best translation, there is always a certain level of deterioration, of data loss, so to speak. The translator may compensate and create something uniquely good as they rewrite the work in a new language, but it will inevitably be missing aspects of the original.

When you write in a tiny language, you do it with the full knowledge that only a handful of people will ever be able to fully appreciate your work. This is both profoundly sad and very beautiful. And it makes me feel deeply connected to people writing in languages that are completely closed off to me.

I think there is a big difference between English speakers, whose native language is the lingua franca, and everyone else. Knowing a language is genuinely exclusive. And that, in our modern (Western, privileged) world, is strangely rare.

The era we are living through is, in my opinion, characterized by a dizzying abundance, not only of material things and information, but of the experiences available to us. In Armelo, I examine the role of travel in our lives, and how astonishing it really is that any one of us (rich westerners) is able to visit almost any place our hearts desire on a moment’s notice. You get to try any food, any clothes, any lifestyle. It is an extraordinary privilege but also disorienting and flattening. This shouldn’t be so easy.

When you dip your toes into a foreign language, you gain a sense of depth, of how much you really don’t know about a place and a culture, and to me there is a pleasure in it. A quick visit to another country usually makes me skittish, but staying somewhere for a longer period, making a fool out of yourself in the grocery store every morning—that’s satisfying.

Goldwyn: Here’s a question I ask almost every writer who is also fluent in English: why do authors not translate their own work? No one knows your work better than you, so why don’t you translate it yourself?

Helgadóttir: Ultimately, I would rather spend my time writing new work. And a talented, native-speaking translator will probably do a better job anyway. I have tremendous respect for the translator’s work and skill set. For a writer in a small language, translators are probably the most important people in their professional lives, and I am lucky to have a wonderful working relationship with fantastic translators like Larissa Kyzer.

I occasionally do translations into Icelandic. Last year, I translated some poetry by two of my favorite poets, Ilya Kaminsky and Kaveh Akbar, while hosting them in Iceland, which was glorious.2 Much more rewarding than translating my own words.

But then I end up not taking my own advice. I have dabbled in translating my poems. I mostly end up rewriting them, which is fun.

Goldwyn: Thinking more about Thingvellir as a place of multiple meanings and an intersection of past and present stories, let’s figuratively walk over to the site of the Drekkingarhylur—the “drowning pool” at Thingvellir, where women convicted of certain crimes were executed—because my second question relates to gender. Iceland’s most famous literary exports are still the medieval sagas, a genre written by and about men, especially men at war—Vikings and warlords and feuding farmers—and the first woman writer in Iceland, Torfhildur Thorsteinsdóttir Hólm, did not begin publishing until the 1880s.

But you are also a part of Svikaskáld (Impostor Poets), a women’s writing collective. Calling it “Impostor Poets” is, I gather, a subversive way of reclaiming women’s place in literature and supporting other women writers? Can you tell us a little about the collective? Was it a response to the limited opportunities for women to write and publish in Icelandic? What is the historical and current state of women’s writing in Iceland, and how do you see your work and the work of the collective within that tradition?

Helgadóttir: First, let me beg to differ a little bit: Many of the sagas feature incredible female characters, larger-than-life women who pull the strings and drive the action, even as the men are committing most of the violence.

But to your question: the collective was born as a way forward, a deliberate leveraging of our admiration for each other’s work against our own impostor syndrome as young writers. It was never intended to be specifically feminist in our output, but it is also not a coincidence that we are all women. We take our experiences as women seriously as subject matter, but we don’t fetishize them either.

Being a part of the collective is like being in a band. I love working with the collective part-time and as a solo artist the rest of the time. I think many writers could benefit from doing more collaborative work; it is an antidote against the crazy-making solitude of the work we do.

What started as a punk project—going away to write a book of poetry over a weekend and then publishing it—ended up becoming a force of its own in Icelandic literature. Perhaps my favorite outcome of this project is the fact that we have inspired other writers to form their own collectives, younger women and young queer poets, for example.

What started as a punk project—going away to write a book of poetry over a weekend and then publishing it—ended up becoming a force of its own in Icelandic literature.

Iceland, as you know, is quite progressive. We had a woman president before I was even born. We have so many brilliant women writers that I never assumed, growing up, writing was a man’s job. And yet . . . and yet, the vestiges of patriarchy remain, like pollution in the groundwater. Men’s subtle sense of entitlement. Women’s trained impulse to relinquish space and power. It can be quite disorienting, actually, growing up assuming equality and then running into all these invisible roadblocks, many of which are inside your own head.

As for my writing, I am always very aware of gender when I write, but I have made the deliberate choice not to focus on it. Toni Morrison said, “The function, the very serious function of racism, is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” I feel similarly about gender. If I was writing about sexism, I would not be writing about other things. There are certainly stories about injustice that need to be told, important stories that I celebrate wholeheartedly. But my personal approach is this: I consider myself a writer first. My stories, with their mostly female protagonists, are universal. I insist on being treated like a male writer would—while acknowledging that I might not have been able to adopt this stance had I been living in a less equal society.

Anyway, you should read Icelandic women. Kristín Eiríksdóttir, Bergthóra Snæbjörnsdóttir, and Frída Ísberg are among our world-class contemporary writers available in translations.

Goldwyn: Are you working on anything exciting now that you want to tell us about? Or where do you think your work might take you in the future?

Helgadóttir: I do have a little nursery of works-in-progress camping out in my computer at all times. But the next one up is a novella—another first! It deals with time and memory, climate, lust, and old printing presses, and will be out in Icelandic next year.

October 2024

Salt

by Thórdís Helgadóttir

translated by Larissa Kyzer

It is an optical illusion one either sees my father

or a shaker of salt you were on a strict diet

no pink fish no fatty fish

no fish but cod

No onion but then you got a taste

and ate nothing but onions for a year

I would recognize your mug

by the scent coffee like mother’s milk

by the dregs a hard crust of sugar

I would break with a teaspoon

you gave my children salty pastilles

if I brought them to visit allowed grasping hands to reach

up to your desk their teeth

diamonds not pearls stuck together

black saliva trickling out of soft mouths

It used to be licorice pirate coins

in a blue cupboard I stopped eating meat

I stopped eating I weighed juice-soaked minerals

on my upturned palm

but they refused to take form I ate salmiak drops

Pregnant and the placenta shriveled

My favorite princess wore a dress

made of every kind of feather and loved her father

the way meat needs salt You either see her

your daughter or a pile of grime

It is an optical illusion I have spoon-fed

you a line of trout I salt my food before tasting

I am all grown up I see people

where my parents once were

otherwise nothing has changed

Somatomancy

by Thórdís Helgadóttir

translated by the author with Larissa Kyzer

In this poem, the lines will be hairs,

my lifeless parts, a weight

driving my head back

and my eyes upward.

Lent sees intermittent

snowstorms when the children

open their mouths, it isn’t words

falling out, but teeth

and the holy ghost whenever

they break open an egg

or an eye, to find that sleep

has turned a crown to a coin.

Life is understanding nothing

less and less. I need a new mouth

for mine is a burrow, a nest built

of silence and pink bacilli

disrupting the clear pure pitch.

An oyster seeks out the salt,

sour, sweet, bitter, bloody

hole in a little one’s gums.

Mirror neurons mime taste buds

teeth mimic pearls;

but from the back they’re scissors,

sharp blades embracing.

The premise for a human is knife.

Between neck and chuck,

skin and canopy, woods and lodge.

To cut the string

when the balloon sags

and we still tend upward.

To release the load just as soon

as it rises from our heads

Larissa Kyzer is an Icelandic to English literary translator and writer currently based in Brooklyn, New York.

1 Halldór Laxness (1902–1998) won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955; he is the only laureate from Iceland. Independent People (Sjálfstætt fólk, 1934–35) is considered his greatest work.

2 Ilya Kaminsky (b. 1977) is a Jewish American poet, born in Odesa, known for Dancing in Odesa (2004) and Deaf Republic (2019). Kaveh Akbar (b. 1989) is an Iranian American poet and novelist, born in Tehran, known for the poetry volume Portrait of the Alcoholic (2017) and the novel Martyr! (2024).

3 Kristín Eiríksdóttir’s (b. 1981) novel A Fist or a Heart (2019), translated by Larissa Kyzer, won the Icelandic Literary Prize. Bergthóra Snæbjörnsdóttir’s (b. 1985) poetry collections Daloon days (2011) and Flórída (2017) have won several Icelandic literary prizes. Frída Ísberg (b. 1992) is the author of The Itch (2018) and The Mark (2024).