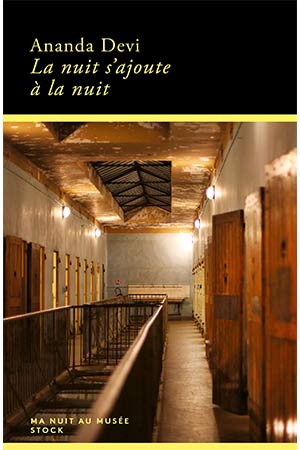

La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit by Ananda Devi

Paris. Editions Stock. 2024. 304 pages.

Who would have thought that Alina Gurdiel’s idea to put a Japanese tradition on its head would have such editorial success? Her “Ma nuit au musée” series, offered by Stock since 2018, counts twenty-one volumes and has been extremely well received in France and around the world. Everything in the series, however, is the opposite of the art practices on Naoshima Island, where art is installed outdoors or exhibited close to large bay windows and skylights and is open 24/7 to the public. Gurdiel asks one author to lock themselves in an indoor museum’s finite space for one night to explore solitude through an introspective conversation. Does the resulting book reveal the author’s inner structure and culture to the world? Does it provide a broad cultural Baedeker for the museum’s collections? Does it create virtual, vicarious cultural knowledge, saving its readers the trouble of discovering and interpreting?

Ananda Devi initially considered the Château de Ferney for a lively debate between Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire ending in a party à trois worthy of the Marquis de Sade. Yet, being an author who, in the words of her translator Jeffrey Zuckerman, doles out “darkness and beauty in equal measure,” she chose a place of incarceration for humans: the Montluc prison in Lyon. From the very start, her stay in this crucible of darkness is inseparable from the beacons of light of her beloved Western cathedrals and from the relentless search for the triumph of soul over body. She keeps using doubt, her favorite modus operandi, and peppers her narrative with interrogations about what and how to write this new book—something she has quite adeptly explored throughout her long writing career of twenty-three novels, countless short stories, and five volumes of poetry.

Devi’s stay in Montluc prison during one dark, rainy, and cold night awakened a slew of “violent memories” that made her toggle back and forth from the “absolute deafness” of the act of writing back to “the din of reality.” In the darkest hour of the night, at 4 a.m., when fate decides between life and death, she receives the gift of clarity. She is ready to witness, to relate emotions and feelings; although her narrative will contain a slew of historical events and citations, she will not write a metanarrative. This choice makes her feel “perfectly gathered” and “inside myself.” It takes her six hours to shed her nagging imposter syndrome, which casts doubts about her project and herself. Six hours to shed a multigenerational feeling of shame that originated with her forebears’ exile from the southern state of Andhra Pradesh on India’s east coast in the nineteenth century, followed by their descendants’ peregrinations in South Africa and Mauritius Island. Six hours to relate numerous stories of social, linguistic, and national degradation, exclusion, and resistance and rebirth to finally be able to make the Montluc prisoners’ experience hers.

Devi’s entire experience with La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit (Night upon night) is presented in a chiastic structure. Progressing from prewriting, previsit stages (chapters 1 and 2), her narrative plunges into a detailed explanation of her approach to her writing assignment. This is mirrored by her postvisit writing and her disclosure of “The Sixth Life,” a previsit fictitious short story about the reopening of the prison to migrants whom she considers to be today’s “genocide of the poor” (chapters 13 and 14). Chapter 3 recounts her arrival at the prison and settling for the night, while chapter 11 sums up her last walk through the cells at dawn. Chapters 4 through 10 recount her visits to the prisoners’ cells and read like stations of the cross.

Devi’s first stop is at the cell of the Izieu children of World War II and adolescent female resisters; her last stop will be for the infants and mothers of the common-law female prisoners as late as 2009. Her second visit is for the World War II male resisters, and her next-to-last visit is for the Algerian prisoners of war, Jean Moulin, and Marc Bloch. At the center of these visits are the cells of two men, André Devigny, a World War II resister famous for his daring escape, and Klaus Barbie, “the butcher of Lyon.”

The descriptions of the cell visits are interrupted by rhizomes—short vignettes triggered by a detail that prolongs the central story with true stories—be it the phenomenology of the body’s degradation and pain under confinement and torture, the evocation of cathedrals, her own upbringing on l’Ile Maurice, slavery, violence toward women, or Bobby Sands’s hunger strike. These rhizomes function like throbbing cries of anguish and reality checks, avoidance mechanisms, deep introspection, and sober assessment. Citations from former prisoners’ memoirs also provide perspective, like Michaël Ferrier’s memoir, Scrabble, where she found the title for the book. Devi also cites Zionist writer André Spire’s phrase that survivors have acquired “an infinite sort of knowledge that cannot be transmitted.” This is where suffering separates the soul from its dross.

The deepest lesson from La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit is Devi’s interrogations about the “infinite chain of pain,” the coexistence of good and evil in each of us, and human responsibility. Did Devigny, the intrepid resistant of World War II, torture Algerian prisoners during the Algerian War where he served? How about Barbie, who rendered countless services to the CIA during the Cold War? Devi’s long night’s journey through the contrapuntal phases of herself leaves her and us with a painfully clear question: what choices would she have made? Her question about how to balance living in a happy cocoon and letting the tragedy of the world devour us has an urgency that makes La nuit s’ajoute à la nuit a must-read book for our troubled times. (Editorial note: The January 2025 cover feature is devoted to Devi winning the 2024 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.)

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin