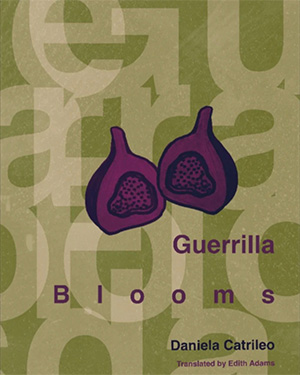

Guerrilla Blooms by Daniela Catrileo

Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Eulalia Books. 2024. 218 pages.

With Guerilla Blooms, Chilean poet Daniela Catrileo, bilingual in Spanish and Mapudungun, creates a poetics of resistance in the language of the Mapuche, the indigenous people of Chile. The Mapuche people resisted the colonizing Europeans as long as they could, until their land was stripped from them, resulting in an urban diaspora to the cities (see WLT, Jan. 2018, 59).

As in the case of other Indigenous languages of Latin America, the almost certain extinction of the people and the culture was avoided through intense family and cultural ties, and a mother language that not only provides connections to heart and heritage but also to a way of making meaning that firmly counters those of the colonizers. The fact that both systems of language and thinking exist within the same people creates not so much a conflict but a powerful resistance, and a counter to the erasures, the deep existential wounds carried by survivors of rupture, violence, and silencing. In fact, only 10 percent of Chileans identify as Mapuche.

Guerilla Blooms consists of four long poems. The Spanish text appears with the Mapudungun line directly underneath it, in a lighter gray font. The appearance suggests erasure and echoes the themes of the poems, which embody Derrida’s notion of the “trace,” which is the embodied set of meanings and potential signification, even as the word itself is problematized.

The first long poem, “Revuelta de cuerpos celestes” / “Revolt of celestial bodies,” forges connections to the ferns, fog, husks, and other physical bodies on earth, while keeping a connection to one’s point of origin in the sky. Throughout the poem are harbingers of destruction: “in this piece of the world / it’s always about a comet” // “en este pedazo de munco / siempre se trata de un cometa.” The compound nature of the Mapudungun is placed in sharp relief, and translator Edith Adams shows us that the single word “Relámpago” (lightning) is “Llüfke Küf” in Mapudungun. The poem and the energies are obsessed with the act of wounding, of exterminating people and culture. The speaker is “quemando mis huellas / hasta hacerlas desaparecer” (burning my footprints / until they disappear).

The poem “Mantra of the Offense” explores resistance to erasure, speaking to the god that holds the secret of the final eclipse. “Apocalypse Song” is not only a powerful, vivid poem about the savage fires of war, weapons, and wounds, it is also about how defeat results in a redoubled effort to maintain kinship connections. The final poem, “PostWar,” is a counter to exterminating existential trauma. The role of the poet is to create songs to “snuff the glow of war / in this final dance.”

Catrileo creates a poetics of resistance and reverberation; the preservation of an alternative way of interpreting the world and its histories possesses sounds and intonations that ultimately invoke the spirits of the past. The poetics relies not so much on hierarchical structures built into interpretive strategies of language and poetry but more on compound images embedded in the language itself. Juxtapositions of images, and the compound words themselves, have emotional and experiential anchors to a collective knowledge within the Mapuche, no matter how fragmented they might be in their diaspora. The connection may be by means of a wound, but the result is the invocation of a trans-Indigenous force known by names ranging from Quetzalcoatl to Ngünechen, Negrita, Ñaña, and Compa, to prepare for “the savage downpour of tomorrow.”

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma