Editor’s Note

. . . you move the thick needle between the threads of the warp

and fasten and return to the other side with the same calming motion.

—Avigail Antman, “Warp and Woof,” trans. Linda Stern Zisquit

In “Untranslatable,” Veronica Esposito’s ongoing column dedicated to words that vex our ability to translate them, she writes in the current issue that “translatability is a concept that exceeds the linguistic sphere.” Most practicing translators will surely agree with such an assertion, given that no language exists in a cultural or historical vacuum. Esposito explores the term han, which is “expressive of something deeply Korean” and has to do with “resentment, sorrow, and regret.” Scholar Hellena Moon claims, according to Esposito, that “it is not the uniqueness of han that makes it untranslatable, but the unique experience of suffering that in and of itself is always untranslatable, and that melancholy marks any colonial and postcolonial context.”

In “Untranslatable,” Veronica Esposito’s ongoing column dedicated to words that vex our ability to translate them, she writes in the current issue that “translatability is a concept that exceeds the linguistic sphere.” Most practicing translators will surely agree with such an assertion, given that no language exists in a cultural or historical vacuum. Esposito explores the term han, which is “expressive of something deeply Korean” and has to do with “resentment, sorrow, and regret.” Scholar Hellena Moon claims, according to Esposito, that “it is not the uniqueness of han that makes it untranslatable, but the unique experience of suffering that in and of itself is always untranslatable, and that melancholy marks any colonial and postcolonial context.”

Beyond the linguistic sphere, translatability can apply to the ways in which artists transpose language into comics, sculpture, dance, theater, painting, music, film, and other media, just as writers incorporate nonverbal elements in their poems, novels, essays, and plays. The twentieth-century Russian linguist Roman Jakobson had a fancy term for this sort of translation in his classification system: “intersemiotic transposition,” which embraces transference between one sign system and another. Among the artists featured in this issue, Gambian musician Sona Jobarteh, Russian American composer and lyricist Vernon Duke, and K-pop group BTS all manifest translatability in their work. Writing about the Korean folk song “Arirang,” Esposito notes that “some even call it the ‘anthem of han,’” a further manifestation of art’s ability to interanimate spheres of language, culture, history, and affect.

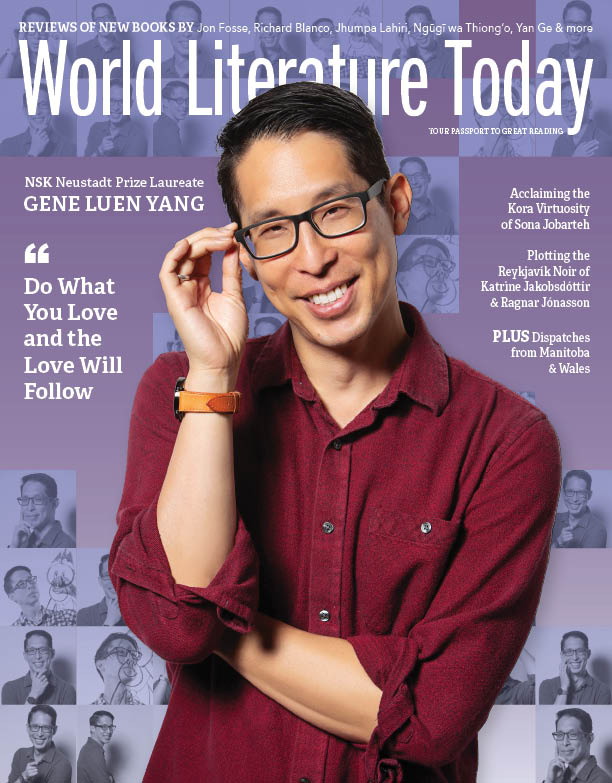

In his essay “The Hybrid Languages of Love and Comics,” which pays tribute to Gene Yuen Lang in this issue’s cover feature, Trung Lê Nguyễn—an award-winning Vietnamese American cartoonist, artist, and writer—beautifully exemplifies this idea of a linguistic and semiotic hybridity embodied in hybrid artistic forms, placing such creativity in the context of his parents’ immigration to the United States. “Comics are this unique medium,” he writes, “where both the images and the text and the words exist together as a common text.” Such hybridity allows comics creators like Yang and Nguyễn to bridge cultures, languages, and generations.

In a sneak peek from Yang’s forthcoming book Lunar New Year Love Story, illustrated by LeUyen Pham, we get a glimpse of the budding romance between Val and Carson, who are making plans to celebrate Valentine’s Day together. In just a few lines of deftly illustrated dialogue, Val expresses her disdain for the commercialized holiday, but by the last cell she imagines herself all dressed up on February 14 and about to receive Carson’s gift. Readers will have to track down a copy of Lunar New Year Love Story to discover just what the gift entails, but I hope that the rest of the current issue dramatizes the many ways in which translatability is not just a linguistic enigma but a creative and collaborative cultural practice.

Daniel Simon