The First 100: Saturdays with Stella

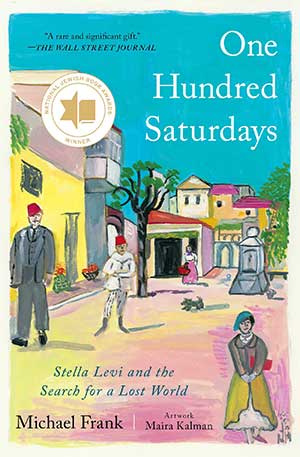

When reflecting on the experience of interviewing his own grandfather into his one hundredth year, Matt A. Hanson finds a kindred methodology in writer Michael Frank’s patience as he interviewed Holocaust survivor Stella Levi for One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World (Avid Reader Press, 2022).

“The first hundred years are the toughest,” my centenarian grandfather said, months before passing away. Born in 1915 to Romaniote Jews from Ottoman-era Ioannina who resettled in New York, his birth certificate reads that his parents were from Turkey, sharing imperial history with Rhodes—Stella Levi’s birthplace—the Greek peninsula, and every other Aegean island. (The Romaniotes are a Greek-speaking ethnic Jewish community, of ancient Roman citizenship, native to the eastern Mediterranean.)

The day he died I was unreachable, summiting Mount Olympus at the start of my first trip to Greece. I spent that evening in a mountain hut, listening to musicians sing in my grandfather’s parents’ mother tongue. After climbing the hanging monasteries of Meteora, I returned to Thessaloniki, where I received the bad news late in the evening and said kaddish.

My host gave me a bottle of ouzo, so I hit the streets, slept on a cold floor, searched for signs of the afterlife in the city’s churches and synagogues. But I did not find the Jewish cemetery, destroyed by Nazis, its grounds now covered by a university campus. The Nazis also deported 95 percent of the Jews of Thessaloniki, a painstaking annihilation even by their standards.

As the largest population of Jews from modern Greece, Thessaloniki’s Jews made up a quarter of the Ottoman Jewish population at the turn of the twentieth century. Nearly sixty thousand ended up in Auschwitz, where Primo Levi, in his 1997 book of interviews, The Voice of Memory, noted a certain classism between non-Ashkenazim and those speaking Yiddish, whom Germans favored.

So, Greek Jews stuck together. Stella Levi remembers as much in One Hundred Saturdays, as told to writer Michael Frank and illustrated lushly by Maira Kalman. Arriving in Auschwitz in 1944, her first time off the island of Rhodes, Sephardim from Thessaloniki greeted her in their common Judeo-Spanish, imploring mothers to give their babies to elders. They did not explain that by doing so they might avoid execution.

So, Greek Jews stuck together. Stella Levi remembers as much in One Hundred Saturdays, as told to writer Michael Frank and illustrated lushly by Maira Kalman. Arriving in Auschwitz in 1944, her first time off the island of Rhodes, Sephardim from Thessaloniki greeted her in their common Judeo-Spanish, imploring mothers to give their babies to elders. They did not explain that by doing so they might avoid execution.

In the barracks, Stella and her gang of Jewish women from Rhodes had to prove that they were Jewish to Yiddish-speaking inmates, forced to bless candles in Hebrew—which they blended into the Spanish dialect they had preserved on the other side of the Mediterranean with songs and idioms intact since the fifteenth century, albeit flush with multicultural, Ottoman influences.

Primo Levi—no relation to Stella—appears throughout Frank’s book. His writing introduced Stella, like many, to the camps as they exist in literature, as a storyteller’s memory. It was at the Centro Primo Levi in New York where Stella asked Frank if he might help her edit a speech she’d planned to give about her childhood in Rhodes.

Frank—who says he even takes notes while talking with his mother—arrived at her apartment with his laptop, ready for what would become the first of a hundred Saturdays. He describes their meeting as an encounter, unwitting. Coincidentally, his 2017 memoir, The Mighty Franks, foregrounds his unruly aunt, who turned one hundred on May 5, 2023, and was born the same year as Stella.

Acknowledging that Stella’s memories are not historically accurate, Frank’s book is more about elderly remembering and intergenerational listening than a validation of Stella as a storyteller. He patiently teases out memories that she is reticent to share, especially from the camps, because she struggles to identify with the Stella who survived the horrors she so bravely relays.

The unimaginable silence of losing a community to the wars of modern history, without hearing them speak in their own voice, surrounds Stella’s survival testimony. Frank and others who have written about Stella—such as Ingrid D. Rowland for the New York Review of Books—talk of millennia of Jewish presence in Rhodes, yet they outright neglect preexisting Romaniote Jews.

Ignoring their shared Greek-Romaniote roots, Frank mentions the “Broome Street synagogue” congregation, members of which accompanied Stella on one of the many trips back to Rhodes that she’s taken since the 1970s, suffering its emptiness as none of the over 1,700 Jews deported returned. (Only a very few saved by Turkey’s sole Righteous among the Nations, Selahattin Ülkümen, could remain.)

Like Rowland, Frank is inconsistent when it comes to the ancient legacy of Jewish Rhodes. Before the Ottomans, the Knights of St. John ruled the island. Obeying the Spanish Inquisition, they killed local Jews from the Greek-speaking, late Roman world, who remained unassimilated only west of the Pindus—where my grandfather’s parents fled, like Stella, bound for New York.

I found a kindred methodology in Frank’s patience—his suspension of disbelief and tolerance for deep silences, the recalcitrant fits and starts—when reflecting on the experience of interviewing my grandfather into his one hundredth year, hearing yarns that went back to 1919, when he described witnessing parades of veterans returning from World War I on a Lower East Side rooftop.

“Aren’t you supposed to ask me a question to get me going? Like where I was born, or my first memory, or something like that?” Stella asks Frank in her temperamental mix of unfussy Aegean islander and colorfully irreverent New Yorker. Only after the first third of the hundred chapters does Frank get her to open up about her youth in Rhodes.

With a haphazard nonlinearity, Frank’s lucid prose is rich but often meandering—at times pedestrian as he and Stella while away time retracing steps that have long faded beyond evidence, despite his laudable efforts to offer parallel, research-laden commentary. Moreover, Frank’s prose can succumb to slack, orientalist tropes as he writes about her naïve balancing act before Western modernity.

Stella, to Frank, is Scheherazade, from the “Middle East.” While he makes serious efforts to transliterate Ladino, Ottoman Turkish is displaced by stereotypical Arabic defaults. Stella’s father wears a djellaba instead of a kaftan, and her family goes to the souk. If minor, these inaccuracies reflect oversights concerning the book’s main theme of hyperlocal traditionalism confronting global modernity.

For all her multilingualism, Stella identified mostly with the language of her occupier, Italian. Her first loves, however platonic, were Italian men. At fourteen she packed a bag, aspiring to study at university in Italy. Her mother, a closet modernist, did not discourage her—but such futures were unheard of in La Juderia, their beloved district by the northernmost port of Rhodes.

In 1938, when Italy adopted fascist, anti-Semitic racial laws modeled after Nazi Germany and imposed them on their colonial possession of Rhodes, it was the beginning of the end for Stella, who—although she was the only young woman to keep studying in shadow schools—never fully recovered from her stunted intellectual growth.

In her mid-nineties, enrolling in Hebrew studies, her diehard will to self-educate resembled that of my grandfather who, aiming for a college degree, worked at a factory until he was seventy, a fatherless firstborn son with five siblings who grew up during the Depression. But in retirement, he proudly enrolled in university, drawing on his close readings of classic and contemporary literature.

The double-edged sword of modernism had come for the Jews of Rhodes. Stella’s stories are the last gasp of her community.

The double-edged sword of modernism had come for the Jews of Rhodes. Stella’s stories are the last gasp of her community, rattling off folk remedies and immemorial superstitions that mark Frank’s account with a vibrant authenticity. But her generation was on their way out. “If there’d been no war we would have left anyway,” she told him.

That the Jews of Rhodes left as they did—unwillingly, enduring the longest Holocaust transport by duration and geography, taking one Jew from the isle of Leros as they went while erasing thousands of years of Jewish life in Greece, literally overnight—is now an eternal flame that will forever ignite historical inquiry for as long as people are literate.

At the intersection where the way back joins with the path forward, as enlightened scholars rifle through facts and myths, the voice of Stella—having entered published letters—will inspire not because it confirms objective record-keeping but because of its emotional intelligence, communicating firsthand experience.

To process the transformational effect of their dialogues, Frank resorts to Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay, “The Storyteller,” in which he conceives of Stella as a traveler whom he likens to Odysseus—returned from the story of her life only to reach an innocent ear and pour into it her Proustian remembrances, distilled into narrative and, finally, wisdom.

Another of Frank’s novels, What Is Missing, is analogous to the multigenerational relationship he built with Stella, both books weighing Old and New World realities between Florence—where Stella spent a significant time after the war—and New York. Stella’s memories merged with Frank’s telling and, through him, became stories. Their symbiosis is as essential as that ephemeral reality which they convey.

If Primo Levi was one of the first to set the camps to the page, Stella’s is a late eyewitness retrospective. Frank calls her the Last Survivor.

To read One Hundred Saturdays is to risk being deeply moved by its stoic act of connection. Frank is unafraid to ask Stella a number of questions that might have been impossible at first, had they not developed trust. If Primo Levi was one of the first to set the camps to the page, Stella’s is a late eyewitness retrospective. Frank calls her the Last Survivor.

Istanbul