The Last Greeks of Literary Imbros

The Turkish island of Imbros represents a historical anomaly of Mediterranean geopolitics. Matt A. Hanson traces the tenacious attempt by the island’s Greek-speaking community to hold onto their history, language, and culture.

Out of the volcanic emergence of Imbros, bald, beige rock and spiky, arid shrubbery stands against high, seasonal winds along sharply ascending cliffs and sloping goat paths where trees grow sideways and stones retain the shape of magma bubbles. Surrounded by frothy blue waters that lap from shore to shore across the archipelago of neighboring isles, most intimately Samothrace, its hoop of hazy coastline appears clear over the north Aegean Sea.

In the steep, hilltop village called Gliki—“sweet” in Greek or Bademli, “with almonds,” in Turkish—the clank of bells softens the silence of somnolent, aging hamlets as sheep roam, their coats painted blood-red and cobalt-blue, ostensibly to signify property amid respective pastoralists. Clicking their hooves, bleating, they skip under the gnarled almond, mulberry, and olive trees shading tightly knit cobblestoned alleyways lined with medieval stone houses.

Traces of modernity appear in stark relief. An electric car-charging station appears affixed to the exterior wall of a well-kept home, made of locally quarried rock beside an overgrown property in ruins. The latter’s fragmented foundation is reminiscent of the Hellenistic ancients whose polytheistic memory still carries whispers of worlds millennia older than that which remains today, relatively unchanged only to the naïve, wayward passersby.

There is more than one way to see Imbros. The largest of Turkey’s island territories goes by at least two names. The Turkish, Gökçeada, means “heavenly.” In Greek, its mythological usage, Imbros, recurs throughout Homer’s Iliad. In the epic of the blind poet, an undersea cave lies midway between Imbros and Tenedos (another of Ankara’s modern-era possessions known in Turkish as Bozcaada). Poseidon kept his horses there before meeting Achaeans, early Greeks.

Such stories, while far from Enlightenment reason and the religious revolts of national history, bolstered the majority Greek populace. Their present, regional identity justified the acquisition of all but these two islands amid the hundreds that exist in the Aegean Sea. After defending itself during World War I, and reforming from empire to nation-state, Turkey successfully vied for territorial sovereignty over the Dardanelles strait, placing Imbros in a precarious geography.

After signing the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, the indigenous Greeks of Imbros were imperiled but not expelled. Along with their counterparts in Tenedos and Istanbul, the Turkish state afforded their people, who then numbered around five thousand, to remain while their brethren in Thrace and Anatolia did not enjoy such privileges and were forcibly migrated, under pain of death, to the Balkan peninsula where they were doubly ostracized, cursed as “Turk-spawns.”

Generally speaking, Greek-speaking communities in Turkey and former Ottoman territories identify distinctly by the word “Rum,” a measure of historical solidarity, staking claims that hail from Byzantine Roman times. The same goes for the people of Imbros. But more specifically, they represent an island of cultural expression all their own, complete with a local dialect and customs tracing a breadth of time enough to rival the immemorial legacy of Poseidon’s steeds.

The current population of Rum Greeks on Imbros numbers in the hundreds, reduced as a result of systematic dispossession imposed by the Turkish state since the 1960s. This followed in the wake of Istanbul’s 1955 pogroms, known locally as the Events of 1955. (Curiously, deniers of the Armenian Genocide in Turkey refer to that history as the “Events of 1915.”) These acts of genocide perpetrated by increasingly ethnocentric Turkish nationalists reverberate today.

The current population of Rum Greeks on Imbros numbers in the hundreds, reduced as a result of systematic dispossession imposed by the Turkish state since the 1960s.

Contemporary researchers from various disciplines, including history, politics, sociology, and architecture, continue to dissect the notion of displacement as a multitiered phenomenon in relation to the surviving Imbros Rum community. The few elderly Greek speakers in the remote, upland village of Gliki-Bademli demonstrate anomalous, collective perseverance. Their stories have also influenced literature, explicitly in that of the late Turkish novelist Deniz Kavukçuoğlu.

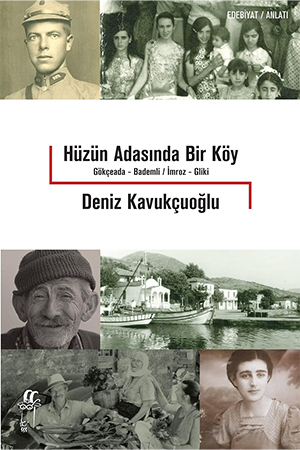

In his literary adaptation of folk history, a postmodernist ethnography of oral histories and photographic ephemera, Kavukçuoğlu explored the interior dimensions of life as a Greek Rum of Imbros in his book Village on the Island of Sorrow (in Turkish, Hüzün Adasında Bir Köy). Published in 2013, this title appeared a decade before the author’s passing in May 2023. He’d been a resident of Imbros, living in an old stone house beside talkative Rum neighbors.

In his literary adaptation of folk history, a postmodernist ethnography of oral histories and photographic ephemera, Kavukçuoğlu explored the interior dimensions of life as a Greek Rum of Imbros in his book Village on the Island of Sorrow (in Turkish, Hüzün Adasında Bir Köy). Published in 2013, this title appeared a decade before the author’s passing in May 2023. He’d been a resident of Imbros, living in an old stone house beside talkative Rum neighbors.

As an exile forced to remain in Germany for a period of twenty-two years while Turkey was under martial law, Kavukçuoğlu was also victimized by the monolithic authoritarianism of the Turkish state during the late twentieth century. When he returned, he became a columnist for the daily newspaper Cumhuriyet, one of Turkey’s last bastions of mainstream dissidence before the media purge that ensued after the coup attempt of 2016.

His home is still festooned with letters in metalwork on the iron entrance gate: “D” for him, and “S” for his partner, Sevgi. They had a spacious outdoor patio, inhabited by families of cats who place their paws on the door to a separate building on the property, a cool kitchen under its own roof beside an open-air fireplace. The main home has low ceilings supported by thick, wooden beams. From its second floor, vast farmlands of the island pasture roll out like carpets.

Every night, its north-facing walls buzz with the sounds of Greek mixing with Turkish as community residents converse loudly in a mood of regular festivity outside their village hall. Posted on its door, the minutes of meetings detail number-crunching and resource crises, such as water use, signed by leaders with Greek names like Stylianos and Efterpi. In the daytime, senior citizens exchange Greek conversation, laughing as they discuss local matters.

Kavukçuoğlu’s book is dedicated to his Sevgi, and the Rum of Imbros, whose voices make up the bulk of his material. The second chapter contains over a hundred pages of interviews conveying the oral histories of the people he sought to portray, and even vivify, by his act of writing with all his senses, to hear of their bitter survival in the face of state violence. In 1963 Turkey built an open prison on expropriated Rum land as part of a larger displacement strategy.

The first full interview testimony that Kavukçuoğlu features in his book is with a woman named Andriana Kondoyorgi-Theodoridis. Born in the village of Bademli in 1956, her father was a shopkeeper, butcher, and blacksmith. She describes him as a beloved man, a good husband and gentleman patriarch. Although she attended Greek primary school in downtown Istanbul, when asked why her family did not move to Greece, she answers Kavukçuoğlu indignantly.

“They are curious why we did not move from Imroz to Greece. When we spoke this was your first question to me, our island house, our lands that we did not sell, why did we not exchange that money. Sell those, get a place in Greece, they said. There’s a thing they don't understand: Imroz-Gokceada was my country. Why would I sell the place where I was born? Is there a logic to that? They don’t want to understand us.”[i]

There is a peculiar sting to the diminishment of the Rum population of Imbros because, between the years 1923 and 1963, they remained dominant on their island and held administrative autonomy within the Republic of Turkey, a sociopolitical anomaly considering the ethnocentric status quo of the nationalist world order. When the community was displaced, their eradication was the final nail on the coffin of Anatolian and rural Rum life outside Istanbul.

But because their diaspora held onto the cultural fabric of island memories, their slow but sure return in the 1990s has been accompanied by nostalgic, Greek-language businesses such as Sten Ada Café, nestling in a corner on a narrow alley in Bademli, displaying photos of black-and-white family histories above its menu of homemade liquors and dairy-rich sweets. Their staff speak Turkish with Greek accents, visibly bearing the weight of their stark losses.

Around the corner from the quaint café, Kavukçuoğlu’s home is within earshot of its patio. Despite an underlying aura of postcolonial oppression, where Kurdish-speaking workers discuss mutual antagonisms during lunch breaks, the surrounding, scenic landscape casts the welcoming space in an aesthetic veneer of philhellenic, culinary retreat. And behind Kavukçuoğlu’s walls, his own family albums speak of long-intertwined Turkish-Greek relations.

Despite their slight numbers—the local Rum population peaked at nine thousand—Turkish scholar Sevcan Ercan showed in her 2020 PhD dissertation for University College London, “Finding the Island of Imbros: A Spatial History of Displacement and Emplacement,” that the Rum of Imbros produce their own body of literature, not only in books but in the form of oral storytelling, as documented by the Centre for Asia Minor Studies in Athens, Greece.

And in the 2007 volume Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics, edited by Marie-Aude Baronian, Stephan Besser, and Yolande Jansen, an article by Elif Babül titled “Home or Away?” conveys the significance of Imbros Rum identity within broader contexts pertaining to diaspora literature around the world. Babül emphasizes the sociopolitical layers behind the sentiments expressed by Kondoyorgi-Theodoridis in Kavukçuoğlu’s book.

As Babül explains: “Additionally as told by the Imbrians living in diaspora, the de-Hellenization of Imbros is coupled with a story of a betrayal on the part of ‘mother Greece,’ mainly as an outcome of Greek reluctance to stand by Imbros at the international political level, at crucial moments of international negotiations. . . . The few elderly Imbrians who refused to move from the island are regarded as the last remnants of the Hellenic culture on the lost homeland.”[ii]

In making that statement, Babül referred to an earlier publication, a 2001 article in Balkanologie by Giorghos Tsimouris, “Reconstructing ‘Home’ among the ‘Enemy’: The Greeks of Gökseada (Imvros) after Lausanne,” in which the researcher, a Greek social anthropologist, concludes by stating that Imbros and its Rum people can be understood in terms of liminality, as a country and community hanging in the balance of two conflicting nation-states’ opposing narratives.

For this reason, literature, and its absorption of oral storytelling, bears a particularly important role in the preservation and revitalization of a culture that has resisted assimilation, both by the state representing their cultural-linguistic heritage and that imposing national order on their ancestral territory. This in-betweenness has come at a cost, as Turkey’s violent streaks of ultranationalism resulted in the murder of a Rum citizen of Imbros in 2019.

The role of literature, and its absorption of oral storytelling, bears a particularly important role in the preservation and revitalization of a culture that has resisted assimilation.

After the killing, Imbros religious leader Laki Vingas said that many Turkish citizens are under the impression that their national minorities are unjustly rich or overprivileged. The cancellation of a memorial exhibition of the Rum community in the year 1964, slated to open in August, followed a similar course of alarms. Its Turkish curator, Melike Çapan, published extensively on the community but abandoned the show over fears of online threats.

In his book’s last interview, Kavukçuoğlu speaks with a Rum born in Istanbul who, because of his Greek name, is asked throughout his life if he speaks Turkish. In turn, Kavukçuoğlu confessed that after his long exile abroad, his native Turkish had come to sound more like writing than speech. Even as many of their voices fade into print, after eight thousand years of presence, Imbros Rum still gather every day to tell stories, eat almond cookies, and dance the hora till dawn.

Istanbul

[i] Kavukçuoğlu, Hüzün Adasında Bir Köy (Oğlak, 2013), 75. The translation from the Turkish is my own.

[ii] Elif Babül, “Home and Away? On the Connotations of Homeland Imaginaries in Imbros,” in Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics, ed. Marie-Aude Baronian et al. (Rodopi, 2007), 46–47.