“The Divine Epilepsy We Call Inspiration”: A Conversation with Mircea Cărtărescu

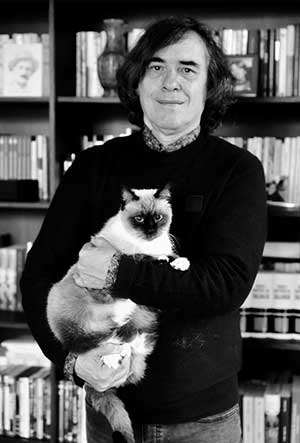

In the world we live in, there are things that happen and things that should have occurred according to the simplest and most basic systems of natural evolution. As we see with insects or even cities, in the works of Mircea Cărtărescu (b. 1956, Bucharest), everything is born, evolves, is built, destroyed, and rebuilt. Each book weaves together stories narrated from the personal to the most extraordinary linguistic and poetic efforts that combine the timeless connections of dialects, poetry, and dreams where several bodies are combined. Always considered one of the most relevant candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Cărtărescu remains humble no matter what prize he wins. His real reward has been the profound recognition of his work, translated into twenty-three languages, and shared by the reconstruction of multiple identities, in the liminal space of a story full of alternations. Whether in the words on his pages or the images he shares with his readers on social media, everything mobile builds an unstoppable bridge to his readers.

Claudia Cavallin: The Blinding trilogy transforms life into a journey, into a flutter on the road. Is your life experience like an insect’s movement that never stops, constantly reborn and dying?

Claudia Cavallin: The Blinding trilogy transforms life into a journey, into a flutter on the road. Is your life experience like an insect’s movement that never stops, constantly reborn and dying?

Mircea Cărtărescu: To be honest, dear Claudia, I kind of forgot Blinding. It is such an old book of mine. Sometimes I think I wrote it in a previous life, when I lived in another house, with another woman, and certainly in another body, for we change completely every seven years. Consequently, not a single atom in my actual body participated in the writing of that novel. Besides, I never reread my books, I forget them on purpose, just as I try to forget how I look every night, to surprise myself in the morning when I look in the mirror.

Insects—mainly butterflies—are the true symbol of our souls and fate in this world, not only because of their beauty, strangeness, and fragility but because of their metamorphosis. This is the most fascinating thing, the radical change they suffer: from a caterpillar, basically a worm, to the miracle of the butterfly. Our fate and dreams are the same. We live our lives on Earth as hairy, egotistic, and voracious caterpillars, but we dream that in our next life, freeing ourselves from the chrysalid of our coffin, we will emerge as winged, wonderful, colorful, gracious butterflies. One of my best stories ever, included in my book called Melancolia (not translated into Spanish yet), is based on the concept of metamorphosis. There I describe a world in which men drop their skins every five years, like locusts, while women suffer the other type of metamorphosis, closing themselves in a chrysalid once in their lifetime, when they are young girls, and becoming magnificent, winged creatures.

I love insects, as many other artists did—think of Nabokov, for example—for they are living fables, living symbols of our fate.

I love insects, as many other artists did—think of Nabokov, for example—for they are living fables, living symbols of our fate. In Blinding, I wrote about the eternal war between the spider and the butterfly—our dark and light sides—while in Solenoid I focused on “the insects’ insects,” the mites, invisible creatures which crawl over our bodies day and night. In Solenoid, I imagined a community of mites, living miserable lives in ignorance and obscurity (as we do), believing they are the only living beings in the whole universe (as we think). A Savior is sent to them from our much higher world to bring them the good news that they are not alone in all of Creation, but they kill him, unable to understand his message of peace and kindness.

And, yes, insects are stroboscopic beings, fast alternations of darkness and light, provoking in an artist’s soul the divine epilepsy we call inspiration.

Cavallin: In The Body, you describe an artificial way of our life as neotenic mammals, trying to stay immature for as long as possible, where insect-like humans sleep in a silk cocoon until they are seventeen, when suddenly, in the blink of an eye, they begin to take flight. Can this figure of developmental stages in insects and humans also be projected onto the figure of the city? Do cities and their political contexts also function as bodies that can be destroyed and rebuilt in your novels?

Cărtărescu: Why not? Cities are also organic. They are living beings. They grow, have mood changes, diseases, symbiotic relationships with their inhabitants, and finally, yes, they can fly. Swift’s Laputa flew, Miyazaki’s city used to fly, and Bucharest, at the end of Solenoid, rises from its place on earth and hovers over the Inferno-like pit full of demons, which it leaves behind.

In my trilogy, Bucharest is of course not only one of the most important places in the universe but is also a very important character, a person—it is myself. My alter ego made of bricks and cement, but also its inhabitants’ nightmares, is present in my poems. Its appearance is never the same in the long row of my books but changes all the time. In my poems, Bucharest is a city of dreams, a sort of a wonderful, high-tech megalopolis, “the most beautiful city in the world.” In Blinding, it already starts to lose its aura, changing “into something rich and strange,” sculptured in my own brain and illuminated by memory; in Solenoid, it is already a ruin, a burnt and degraded city, “the saddest in the world”; finally, in Melancolia, it simply disappears, the city where the stories take place has no name and no feature that could make it recognizable. Here it becomes an imagined city, as in Calvino, full of archetypes, an equivalent of my Jungian subconsciousness.

In my trilogy, Bucharest is of course not only one of the most important places in the universe but is also a very important character, a person—it is myself.

The last of Bucharest’s metamorphoses happens in my most recent novel, Theodoros. Here, Bucharest is an oriental city full of wonders, miracles, color, and poetry. I am not the same all the time; I have many faces and identities. My city is in my image—a multifaceted one, shining like a brilliant place in shadow and solitude.

Cavallin: There’s something about The Right Wing that catches my attention. “Artifacts,” says the character Herman, “show, wherever they shine, in the blind and memoryless earth, in a chaotic history like geological strata, in anomie and the absurd and the inexpressible, that there is no difference between the manipulation of matter and that of spirit, that technology is mystical to those who do not understand it, and that mystique is a technology as yet unknown.” And he adds that we have learned to slip between this world’s total and empty spaces. Today, when technology seems to transcend all geographical boundaries between writing and readers, does online literature return to mysticism or transform novels into cultural artifacts?

Cărtărescu: Obviously, Herman alludes here to the famous law formulated by Arthur C. Clarke, an author he might have known from the sci-fi booklets published in Romania by that time. Advanced technology, Clarke says, seems like magic for the less advanced people (a UFO, for example, is a kind of magic for us). To a cat, humans must seem like a race of magicians, for their masters can turn on the lights in a room, listen to music on the radio, travel in cars, and so on. But for a snail, a cat must look like a magical creature.

You are right. The book, this fantastic mechanism for reading, which for centuries was at the core of the Gutenberg Galaxy, seems now kind of obsolete. For young people, born with a smartphone and tablet in their hands, a book appears as a strange object, belonging to a quasi-forgotten culture. It looks like an artifact, basically made out of wood like an idol, printed with strange monotonous signs like little black ants, a code of some kind. A young child who is used to playing video games on the console all the time might be confused when he sees a book. What kind of spelling does it contain? Isn’t it dangerous? Can it summon dark and mischievous spirits?

And they are right, and Clarke was wrong. Not only that advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic but even more so the old technologies. Magic has nothing to do with time and evolution. Magic is the unknown, the uninvented, or the already forgotten. Magic is the infinite darkness that surrounds our microscopic lives and minds. Books are magic and can really summon ghosts: Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Sappho, Dante, Joyce, Borges. They force them to come and speak in front of us. If you know how to use them, through the magic of reading, you can travel with the speed of thought to faraway realms, inside or outside of yourself (in fact, everything is inside of yourself). The smartphone is the object at the core of our time, and, despite its evident magic, it is a banality for us. But a book or a UFO—a flying saucer, as it was called in the golden years of my childhood—are the real objects of pleasure and wonder: a book is a UFO from the past, and a UFO is a book from the future. Both are hypnotic artifacts made for our thirst for the unknown.

A book is a UFO from the past, and a UFO is a book from the future. Both are hypnotic artifacts made for our thirst for the unknown.

Cavallin: I’m moving to Solenoid because it’s one of the novels that most connects us with existence as an anatomical diagram. In this novel, there is a symbology of the body, and you mention parts and movements, inside and outside. “They were the inside-out human, the human glove with its internal organs displayed, the human Christmas tree with its ornaments of lymphatics ganglions, intestines, glands, and bones, with the tinsel of veins and arteries, while within, the constellations, sun, and moon burned with all their might.” That is outside, but we also have a unique movement inside our bodies. Could this be attributed, at least in part, to the Surrealists’ engagement with Freudian psychoanalytic theories within your novel? Solenoid includes quotes from Borges, and when we are reading, we are living a dream that creates another dream, as we did in “The Circular Ruins.” Are we using our unconsciousness to be part of our dream as a mythical writer?

Cavallin: I’m moving to Solenoid because it’s one of the novels that most connects us with existence as an anatomical diagram. In this novel, there is a symbology of the body, and you mention parts and movements, inside and outside. “They were the inside-out human, the human glove with its internal organs displayed, the human Christmas tree with its ornaments of lymphatics ganglions, intestines, glands, and bones, with the tinsel of veins and arteries, while within, the constellations, sun, and moon burned with all their might.” That is outside, but we also have a unique movement inside our bodies. Could this be attributed, at least in part, to the Surrealists’ engagement with Freudian psychoanalytic theories within your novel? Solenoid includes quotes from Borges, and when we are reading, we are living a dream that creates another dream, as we did in “The Circular Ruins.” Are we using our unconsciousness to be part of our dream as a mythical writer?

Cărtărescu: Surrealism is not only a product of Freudianism but also of Romanticism. Actually, the fantastic realm of dreams, our inner oneiric kingdom, was a romantic invention. Jung was a romantic, even more than Freud. He stepped in the footprints of giants like Hoffmann, Chamisso, Tieck, Jean Paul, Achim von Arnim, and Gérard de Nerval. He spoke about our inner continent full of archetypes, already mapped by Romantic poets and novelists. Later on, the surrealist vision on life and art was exported from Europe to Latin America, where it flourished once again with the label of “magical realism” in the works of García Márquez, Cortázar, Borges, Sábato, Asturias, Carpentier, and many others.

Solenoid can be seen as either a Romantic or a surrealist work, but I think it is much more. I wrote it indeed in a process of self-induced trance, like in a lucid dream. It is almost a thousand pages long, but there are practically no words erased in its manuscript, written by hand in notebooks over the course of five years, and not a single page torn from it. While writing this very complex novel, I decided to diminish myself as much as I could. I became a small and light jockey on the back of my own mind. It is not me, but my mind that did the whole job, like the horse which wins the race only if the jockey is as small and insignificant as he can be. I almost never touched my horse’s back—I levitated above it, leaving the horse free to run and win its own race, not mine. The freedom of imagination was the main rule respected in this novel.

While writing this very complex novel, I decided to diminish myself as much as I could. I became a small and light jockey on the back of my own mind.

Despite its almost total freedom of development, Solenoid is not chaotic, but one of my most rigorous prozastic constructions. It is a demonstration as clear as a mathematical theorem. Mathematics, biology, philosophy, quantum physics, and theology are not as divergent as we think; they are branches of the same tree. Solenoid has all those branches, for it is in fact a “Summum”: an image of what we are, what we know, and especially what we don’t know. It was my way of interpreting Rimbaud’s enigmatic words: “I expressed the inexpressible.” The ultimate meaning of this book is a gnostic one: we were born in a prison, and our duty is to escape from it.

Cavallin: In Solenoid, there is also realism, which details a strange Bucharest. In other interviews, you have described that city as a “nineteenth-century Paris, with a subterranean life, full of mysteries, looking as much like Istanbul or Cairo as like Paris, Brussels, or Vienna” (Words Without Borders). Now that you deeply connect with Latin American culture and readers, what are the most creative and specific details you can relate to our cities right now and in the future?

Cărtărescu: I really love Latin America. This magnificent geographic and cultural continent was my biggest discovery in recent years. I’ve had the chance to visit, so far, very different countries like Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile, and I really felt at home everywhere. I cannot wait to visit the other ones too. You know, Romania is so similar to your countries, from so many points of view, that some people say it is actually a South American country that got lost in Europe. And there is much truth in it: our language is of a Latin origin, as is yours, we had lots of right-wing and left-wing dictatorships in our recent history as you had, there is the same huge gap between the rich and the poor like you have, and—most importantly for me—our literatures are imaginative, explosive, and full of life and love for people. I have met many great and important Latin American writers so far, and I read their books with great pleasure.

Cavallin: Finally, I would like to ask about your last novel, Theodoros. Is there a unique way to travel in time to reconstruct parallel universes and better understand what we are as human beings?

Cărtărescu: I could define it as a pseudo-historical novel and a huge fantasy in a vortex of parallel universes. It covers three thousand years of history, starting with King Solomon in Jerusalem till 2041 in the future (when the world ends), and half of Earth’s surface. My character, Theodoros, is born in Wallachia as a child of a servant, becomes a pirate in the Greek Archipelago, and finally fulfills his dream of becoming an emperor. Among the characters I mention are the Queen of Sheba, Joshua Abraham Norton (the self-proclaimed Emperor of the US), Queen Victoria, her prime minister Disraeli, King Tewodros II of Ethiopia, Prince Ghyka of Wallachia, and, as a special guest star, John Lennon! The story is told by the seven Archangels of heaven for the delight of God, the archetypal Reader. Theodoros is a major work of mine.

February 2024