The Lesser Evil (an excerpt)

In this excerpt from a classic Argentine horror novel, something sinister visits a bathing woman in her new apartment.

“The high heels! The high heels!”

When the doorbell rang, five months ago now, I assumed—since the street buzzer hadn’t provided any forewarning—that it was the building superintendent. This was an optimistic assumption: it was late on a Saturday evening, and the chaos of the move had me on the verge of tears. The movers had not only broken four of my Japanese teacups, a gift from my ex, but several towels and my favorite sweater were missing. All this, without even mentioning the hours I’d spent unsuccessfully trying to force the sides of the bed frame into the headboard.

I opened the door wearing my most winning smile, prepared to accept the super’s offer to help and mentally calculating an appropriate tip. The woman I found standing there did not look at all like a building superintendent. She repeated the strange words about footwear—no Good evening, no Nice to meet you—in a decidedly aggressive tone. She looked to be a few years younger and a few inches shorter than me, with premature gray hairs standing out from the black roots of her carrot-colored dye job.

After a few seconds staring at her with my mouth open, my throat drying out, I realized I had to say something.

“What . . . high heels?”

The woman, undoubtedly convinced that the moment of hesitation confirmed my guilt, unleashed a long monologue. This gave me time to take stock of her horrific fashion choices, from the orange tracksuit with stains on the left shoulder that screamed of baby vomit—I’d guessed it was a second child but later it turned out to be her fourth, a true demographic excess—down to her filthy Nikes and plastic digital watch.

“The high heels! Yesterday it went on all night, until past four a.m., stomping and stomping and stomping. My husband and I couldn’t get a wink of sleep. Some people have to get up for work on Saturday morning, to earn a living. Then today you’re at it again! And since you got started with the noise earlier I decided to come ring the bell, because you’re driving me crazy with all the stomping around, I hear it echoing in my head. Take an Ambien if you have insomnia, or at least do us a favor and put on some different shoes. Have a little more consideration for others!”

“Sorry.”

It wasn’t my apology that halted her torrent of words but the gesture I made, inviting her to look down at the slippers I was wearing. And since the complaints of a neurotic neighbor were low on my list of priorities given the state of my apartment, I was able to remain unruffled. I plastered my winning smile back on and continued speaking.

“A pleasure to meet you. My name is Inés Gaos, and I just moved into the building. You must have heard the catastrophe that the movers created, because I haven’t put on a pair of heels since high school, when I also wore tailored blazers and tons of makeup to make myself look older.”

My cat Azucena chose this moment to emerge from the bathroom, where she had taken refuge from the bedlam, and began to aggressively rub her long black-and-white fur against the dirty Nikes and horrendous tracksuit. The woman, embarrassed by the assault on her new neighbor, saw the animal as the perfect way to apologize without admitting she’d been wrong.

“He’s adorable. Here, kitty, kitty . . .”

“She’s a girl. Females are always prettier than males. They don’t have that fat face, or when they’re neutered even worse . . .”

Although outwardly delighted with Azucena’s friendliness—bending down to scratch behind the cat’s ears—the neighbor had not forgotten the cause of her rage and quickly returned to the point that had unconsciously alarmed me.

“And what about yesterday? Who was walking around last night? Because I live in 15C, right underneath you, and I can assure you it was unbearable. Kitty, kitty; here kitty. What’s her name?”

“Azucena. I named her after the Maizani song, ‘Life slips a-wa-ay and never re-turns.’ Remember that song?”

I can’t say that Nancy’s face—I later learned that the neighbor’s name was Nancy, Nancy Romero—improved much when she smiled, but from the moment she smiled I decided I liked her. Also, she had a lovely singing voice.

“Of course,” she said, “I’m crazy about the old tangos, have been since I was a kid. ‘Dar-ling I want you to show your true col-ors.’”

“You sing beautifully.”

During the few seconds of silence that followed my compliment, Azucena bolted down the hallway. The task of wrangling the cat back inside kept me from committing one of my habitual gaffes, showing my lack of culture by admitting that I like Maizani but not tango in general, or debating whether “Life Slips Away” should even be considered a tango at all. I caught the savage beast just as she stuck her neck between the bars of the stairwell banister and was about to begin showing off her acrobatic abilities. Azucena’s angry yowls punctuated the rest of our conversation.

“Would you like to come in? I think I could probably scrape together a cup of coffee.”

“Thanks, but I have . . . food on the stove.”

No one leaves food on the stove for that long. I pitied her not being able to tell her husband to do the cooking himself, or to wait a few minutes to eat.

“You have me worried with what you said about last night. Are you sure the stomping was coming from this apartment?”

“Well, yes, there’s no one else above us.”

“I don’t think it could’ve been the former owner, he’s an elderly man. And I haven’t been in here. The real estate agent turned over the keys on Thursday, and what could she have been doing until four a.m. in an empty apartment anyway?”

Nancy ran her hands down the sides of her tracksuit and then cracked her knuckles. I noticed that her left eyelid twitched slightly; she was a laundry list of nervous tics.

I noticed that her left eyelid twitched slightly; she was a laundry list of nervous tics.

“I don’t know if Oscar—Oscar is the super—has a copy of the key. But I doubt it was him. I’d change the locks if I were you. A few months back they killed an old lady on the sixth floor, robbery gone wrong. We didn’t find out till two days later, when her niece came to visit and they went in because she wasn’t answering.”

Rereading what I’ve written here—the little I’ve written—I realize I might be creating false expectations: Nancy has been an important part of the drama over the past five months, but she certainly hasn’t occupied a central role, poor thing. The problem is that I don’t have time now to go back and redo this awkward beginning. So I’ll just keep going.

Despite Nancy’s rush to get back downstairs, she wouldn’t leave until I’d promised to lock the door with the chain as well as the deadbolt. She also offered to help me find a locksmith the next day, so I invited her to come back up for a cup of tea. Anyone naïve enough to think they can find a locksmith on a Sunday, or with enough connections in the neighborhood to actually find one, deserves a nice cup of Earl Grey or Lapsang souchong.

I spent a few more hours unpacking. Once the place looked more or less civilized and I could finally sit on the bed without it collapsing, I stopped for long enough to notice that my hands were raw and I had a terrible backache. Like always when I’m exhausted, I could think of only three things: a glass of cognac, a few lines of coke—my dealer had given me an extra baggie as a housewarming gift—and a hot bath.

I started with the cognac, savoring the few drops of Rémy Martin I had left, then pouring Reserva San Juan into the glass. As the first wave of alcohol warmed my stomach and relaxed my muscles, I looked around for the cigarette case that had belonged to my great-grandfather Ernesto. That’s where I stash my cocaine, along with the tube of a ballpoint pen or a new bill and a pocketknife. This conspicuous hiding place is a constant headache, since guests are always fascinated by the antique silver box and can’t resist picking it up and trying to open it. The acrylic picture frame I use to cut up my lines was lying—amazingly among so much mess—on the same pile of papers and magazines as the cigarette case.

Slowly, trying not to seem desperate even though there was no one else around, I cut up two fat lines, snorted half of the first, and turned on my stereo. A deep, melancholy voice came over the speakers. It was a tape someone had left behind at my New Year’s Eve party, the song “Ain’t No Cure for Love” by a singer I can never remember the name of. As I opened the door to the balcony and watched Azucena rub herself against the railing, purring desperately, I couldn’t help but smile sadly at the appropriateness of the lyrics for a cat in heat: “There ain’t no cure, there ain’t no cure, there ain’t no cure for love.” It’s a fact that cheesy, clichéd sayings, which do not speak highly of humanity’s inventiveness, are often pretty accurate. There ain’t no cure for love.

A cruise ship slid over the river, deceptively close to the shore where the College of Engineering building cut through the sky. The boat was fully lit up, one of those floating hotels that sail around the world visiting exotic locales such as Buenos Aires. I love all things superfluous, so the sight of the gigantic vessel—with its gratuitous tons of wood and metal—caused my smile to widen into a stupid, pathetic grimace. I drained my glass, snorted the other half of the first line, and then walked back and forth between the bathroom and the kitchen several times, checking to make sure that the new hot water heater created the optimal temperature. As the bathtub filled up, I poured myself another glass of cognac and finished the other line of coke. The acrylic picture frame threw off a disgusting, blurry reflection of me. One eye closed, face contorted, a fifty-peso bill millimeters from my nose. It’s precisely to avoid moments like these that I never snort off a mirror, the reason I’ve kept this ancient photo of Mom and Dad in the hills of Córdoba just after they were married. I quickly determined how the annoying reflection had been created: the dining room light fixture was very low, right over the center of the table. I hadn’t anticipated this minor domestic inconvenience when hanging the light and vowed to do my lines in the kitchen or the office from now on.

I had just turned off the tap and was about to undress when the phone rang. I froze, arms crossed over my stomach, right hand gripping the left hem of my T-shirt, left hand gripping the right side. I waited for the answering machine to get it, ready to run to the phone if it was Leopoldo, but at the same time certain it would be Alberto. The shrill, metallic screech of the machine was as grating as ever.

“Hello, hello. Are you there? It’s me, your business partner; your soulmate. The place is packed, people are waiting outside. . . . Hello, Inés, helloooo. Dude, pick up! Fine, then, be that way. . . . I’ll call tomorrow to see if you still need a hand with the unpacking. Oh, don’t miss Prince of Darkness, the Carpenter movie. . . . It’s on HBO in a little while, at four a.m. Bye.”

Even though Leopoldo was the one who hadn’t offered to help with the move or even called all day, I had to make an effort to keep my anger from bleeding onto Alberto, who had done both. Leopoldo was a recent addition to my life, and lacking a better label to describe the nature of our relationship, I suppose I would call him my boyfriend. There was no doubt, however, that he considered me his girlfriend. I could easily imagine Leopoldo Vidal Casares, Esq., celebrating his beloved mother’s birthday in La Plata and lamenting the fact that his crazy girlfriend had chosen such an inopportune date to move.

I had a fleeting feeling that there was someone watching me, something moving behind me; then I remembered the mirror I’d hung on the back of the door.

I took off my clothes, put on my shower cap, and set my watch on the closed lid of the toilet. I had a fleeting feeling that there was someone watching me, something moving behind me; then I remembered the mirror I’d hung on the back of the door. I turned around to check it out. This second glimpse of my reflection was much more flattering than the one thrown off by the glare of the acrylic picture frame. I’m 5'8" barefoot, and while I know it’s vain to be proud of it, my figure at thirty-one—I’ll be thirty-two in August—remains as smooth and supple as a teenager’s. But the traces of a life spent partying and a total lack of physical activity can already be seen in the fine lines around my eyes and in my brittle hair, which I now have to wear short. As I stood there, obsessing over these tiny details, vowing to join the gym and start eating better, Azucena resumed her mewling concert. My idea of relaxation does not include a kitten with her paws on the edge of the tub yowling in my face, so I took her into the living room and locked the bathroom door behind me.

The water was boiling. After a few awkward introductory movements—stepping one foot in, then the other; huffing as I kneeled in the tub; stretching out my legs and submerging my torso only to sit up quickly, holding back a yelp of pain—I finally surrendered myself to the heat and shifted all my anger onto Leopoldo and away from Alberto, who had been nothing but kindness and care, as always. By some magic of my physical exhaustion, or thanks to the cocaine and cognac, two superimposed images of Alberto Leboud floated into my mind. One was that short, skinny boy sitting beside me and my teenage insecurity the first day of classes at the Buenos Aires National High School. The other was Alberto, tall and large—6'2", 230 pounds—at Ezeiza airport the day I arrived home following my father’s death, recently divorced and returning from a year and a half in the United States. As I soaped my body, I reflected on how those two memories, much less tawdry than others I could conjure from the Leboud series, were a major part of what made him so important to my personal identity, my self-image, or whatever you want to call it. Alberto isn’t only my oldest friend but the first friend I made in high school. And Alberto is the one who proposed the idea of opening a restaurant together when I stepped off that hellacious Paraguayan Airlines flight with no idea what I was going to do with my life.

Azucena’s squalls were muffled by the bathroom door and had become mercifully less frequent, but she wasn’t contributing to my good reputation in the building. I strained my eyes to see the time through my fogged-up watch face, and it must’ve been between 2:20 and 2:25 a.m. that I may have vaguely lamented that Alberto, because of the busy night at the restaurant, would miss his favorite horror movie. The mere fact that I suspect this must mean that something to the effect crossed my mind, but it wasn’t the most lucid thought: Alberto collects these movies—he doesn’t have to wait to watch them on TV—and anyway he owns a video rental store a block from our restaurant.

I still don’t understand the restaurant’s modest success, which allows me to refuse my mother’s financial help since it always comes with strings attached. I suppose it must be thanks to our proximity to the Casa Rosada, the Supreme Court, and other government buildings, the kinds of places where people make easy money. There are times that I can count thirty mobile phones in the place, which only has twenty seats. If it were up to me I’d turn away half the clientele, but the competition in San Telmo is fierce and our restaurant is too quirky to afford us such luxuries. Considering the Argentine palate, it’s a miracle we haven’t been mobbed in Plaza Dorrego for defacing the country’s most beloved gastronomic symbols: charred steak, soggy French fries, and salads of wilted lettuce, gritty tomatoes, and slimy onions. At Picante, we serve only spicy dishes: Louisiana jambalaya, Bolivian saice, curries from India and Thailand, Peruvian chupe, pork mole, and any other dish that will guarantee a numb tongue and a significant consumption of cocktails.

It couldn’t have been much past 2:30 a.m. when I rested my head on the back of the tub and closed my eyes. I remember feeling overcome by a crushing fatigue, and I didn’t have the energy to stand up, pull the plug, and turn on the shower to rinse off the suds. I must’ve given in to the warm caresses of the soapy liquid and briefly nodded off.

What woke me, if I actually fell asleep, was the smell. It was a nauseating mixture of animal excrement, sulfur, and a dying man’s death bed.

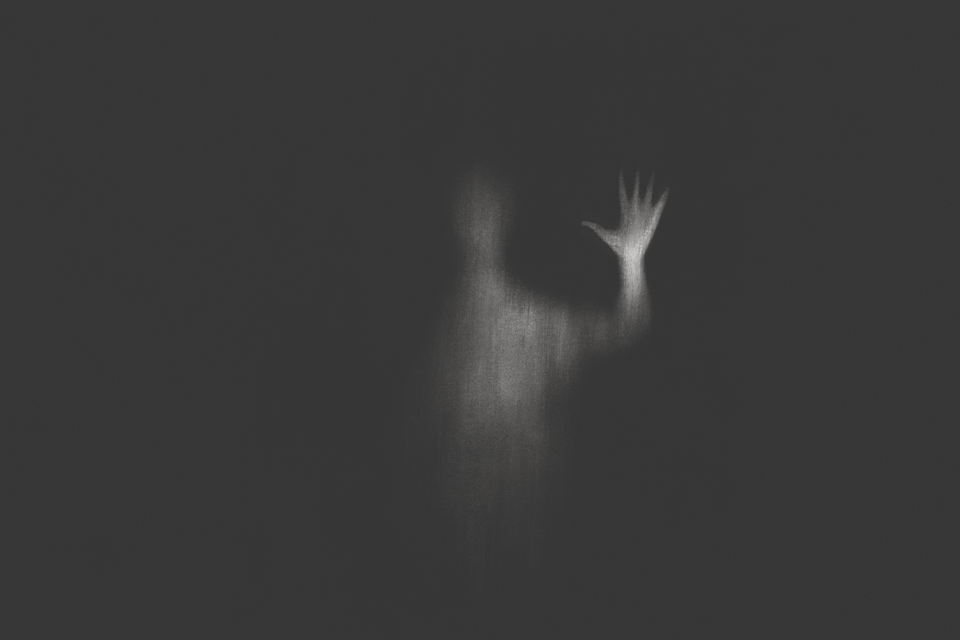

What woke me, if I actually fell asleep, was the smell. It was a nauseating mixture of animal excrement, sulfur, and a dying man’s death bed. As I tried to keep from gagging, I noticed the other surprising change: an intense, freezing cold had invaded the room. My torso was shrouded in fog and my breath exited my mouth as steam. I slipped while getting out of the tub, wobbling with one foot inside, one out, in real danger of seriously injuring myself. My heart pounded, sending a welcome wave of heat through my body. I took several deep breaths, and when the shaking subsided—as suddenly as it had started—I fumbled for my bathrobe. I had just finished tying it up when I heard him. I instinctively jumped back, banging my calf against the bidet and causing a bruise that lasted for days and spanned the entire color spectrum.

His steps were slow, almost timid. The man had a limp—I could hear one of his feet scraping the floor—and he must’ve had metal tips on his boots. (I don’t know why I supposed he wore boots; the fact that it was a man, on the other hand, was founded in my logical fears and prejudices.) Although I felt a fleeting moment of absolute indifference, and even a cheerless celebration over having discovered the mystery behind “the high heels,” panic soon punctured my spine, grabbed me by the throat, and flooded my mouth and stomach. I felt a strong urge to piss myself. I trembled as the presence moved toward me, dragging terror along with him like prey in the teeth of a voracious animal.

His steps were slow, almost timid. The man had a limp—I could hear one of his feet scraping the floor—and he must’ve had metal tips on his boots.

When the man stopped in front of the door, the smell he exuded became somehow more bearable—you can get used to almost anything—but the temperature dropped even further to an icy chill. I had stopped gagging, but I was now shivering uncontrollably. The man’s labored, asthmatic wheezing seemed to come from an inhuman height, as if his mouth hovered above the doorframe, or higher still. I kept my eyes on the locked door as I scrambled to the toilet, grabbed my watch, and sat down. Screaming for help in that windowless room would’ve been as futile as making the sign of the cross or praying. An eternity passed before the man tried to open the door, and when he did I almost cursed myself for having locked it, wishing it could all be over there and then. The door handle moved up and down, slowly, and then returned to its original position. He didn’t shout or force the door. His steps simply receded, as did the stench and the cold.

I waited for ages, straining my ears and listening intently: nothing, not the slightest movement besides the occasional rustling of the living room curtains. I was sitting on the toilet, my knees pressed together and my muscles tensed, about to piss myself. Finally, when I couldn’t take it anymore, I lifted the toilet lid and let loose, the intimate sounds a defiance of that sinister presence. I moved to open the door, resolved to face whatever was out there, but jolted in pain as I touched the handle: the metal was scalding hot, and that brief touch was enough to raise a blister on my palm. I could still feel the blazing heat through the towel I wrapped around the handle.

The office and bedroom were free of intruders. When I reached the kitchen, a disgusting smell set my heart racing once again. But there was no one there. The living room and balcony were empty too, but I realized I hadn’t heeded Nancy’s warning—although I was sure I had—about locking the chain as well as the deadbolt. Then it dawned on me. The smell from the kitchen wasn’t the stench the man had exuded, but a much more familiar odor. I eventually found the cat curled up behind the washing machine, her fur matted with human shit, dead.

Translation from the Spanish