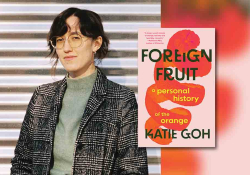

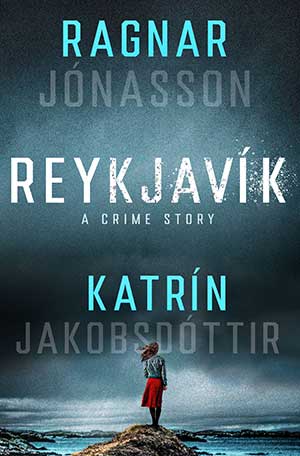

Icelandic Stories: A Conversation with Katrín Jakobsdóttir & Ragnar Jónasson

In September 2023 Minotaur Books published Reykjavík: A Crime Story, co-written by Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, and Ragnar Jónasson, an Icelandic best-selling crime writer whose Outside is being made into a feature film. Already receiving excellent reviews, this story about a mysterious disappearance comes to a head as the city of Reykjavík celebrates its two hundredth anniversary.

In this conversation with Iclal Vanwesenbeeck, the co-authors discuss Icelandic fiction’s strong connection to the environment, their shared love of Agatha Christie, a possible sequel, and much more.

Iclal Vanwesenbeeck: Katrín, you have a graduate degree in literature that focused primarily on Icelandic crime fiction. In the past, you have published various articles in this field. What inspired you to shift from the academic to the creative side of crime fiction? How did your academic research inform your writing style as a novelist?

Katrín Jakobsdóttir: Of course, quite a long time has passed since I wrote about crime fiction as an academic. I started writing about crime fiction in 1999; quite a young student back then, and it felt so interesting because the wave was actually starting then. You know, all of a sudden, we had more than one author writing Icelandic crime fiction. So, it was kind of spreading out; I could feel that it was happening. It was so nice to be a part of something new and exciting, and I was writing about Icelandic crime fiction until I went into Parliament in 2007. After that, I wrote an occasional article, and of course I have always enjoyed reading, but I had never written anything except nonfiction. I don’t have any poems in my cupboards waiting to be published. But it’s a very different thing to write nonfiction, write about others’ works, than to start writing your own. I think it actually helps a lot to have read so many books on crime fiction and thought so much about what makes a good crime novel, so that was actually a strength.

Vanwesenbeeck: Which tells me you are still an academic at heart.

Jakobsdóttir: Yes, exactly. Nothing is ever good enough.

Vanwesenbeeck: Perhaps to follow up on that, Katrín, in your article “Sjöwall and Wahlöö Meet Philip Marlowe or the Coming of the Icelandic Crime Novel,” you note that “during the first half of the twentieth century, the average in Iceland was one crime novel per decade, and that changed in the last decade.” You call this new period the springtime for crime novels in Iceland. In Reykjavík, we see this change expressed in a rather playful paragraph where Sunna and her brother Valur have a conversation about crime fiction in Iceland in the 1980s, and Valur tells his sister, who imagines writing a crime fiction novel in the future, “Like anyone would want to read a detective story set in Iceland.” Please tell us about the distinctive qualities of Icelandic noir. Did it branch out of Nordic noir? What are some stylistic and aesthetic elements that make it quintessentially Icelandic?

Jakobsdóttir: I would say it’s a genre within Nordic noir. What makes it different is that, maybe from my point of view, Icelandic crime novels are extremely diverse because it’s such a small market. Even in that market you have many writers—[to Ragnar] how many writers?—

Ragnar Jónasson: Twenty, maybe more.

Jakobsdóttir: —writing crime fiction in modern times. But within that very small group there is great diversity, and that’s distinctive because we are a small community, so everybody is filling up a certain space.

Jónasson: I think Icelandic noir is also, to be honest, a marketing thing. A publisher will use this for a crime novel to distinguish it as an Icelandic crime plot, so it’s a brand in a way.

Jakobsdóttir: What is very common in Icelandic crime novels, like the Nordic ones, are environment, weather, and space. You can see that also in the Shetlands, in some series in the UK. But it’s a very distinct character of Nordic noir to have such strong connection to the environment.

Nature is a part of our identity. Iceland is so vast and so little of it is inhabited, and we are proud of the nature we have, which seeps into the books. – Ragnar Jónasson

Jónasson: Nature is a part of our identity. Iceland is so vast and so little of it is inhabited, and we are proud of the nature we have, which seeps into the books. Weather is—

Jakobsdóttir: —what you think about every day.

Jónasson: It is because it’s so bad. Also, because one hundred years or even less, fifty years ago, it was a matter of life and death because farmers and fishermen had to get the weather right, otherwise you could die out in the sea. So, it’s in the DNA. It’s not just a pleasant thing we like to talk about. Our ancestors really had to struggle with the weather; it was a hard place to live, and we write about that.

Vanwesenbeeck: In an intriguing aesthetic form, too. We see this manifest reverence for and protective approach to nature, almost in an environmentalist vein. Is nature a fundamental force in Icelandic noir?

Icelanders value the unspoilt wilderness greatly, so they don’t think it’s a given to put a windmill farm there. – Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Jakobsdóttir: There is a strong nature-protection movement in Iceland. I am just coming from the UN assembly where we have been talking about green energy and climate for many days, and Icelanders value the unspoilt wilderness greatly, so they don’t think it’s a given to put a windmill farm there—there is a sacredness to nature.

I have thought a lot about the beliefs of Icelanders. We were heathen, then we became Christian, but when we became Christian, we decided we could stay heathen if we just didn’t tell anyone, so it’s a highly secular society, and religion is not a dominant factor in society. But my theory is, and it’s not a scientific approach, that if you seek spirituality in Icelandic society, you will find it in Icelanders’ views of nature.

Vanwesenbeeck: I know that Ragnar’s inspiration as a crime fiction writer is Agatha Christie, and you both dedicate Reykjavík to her. How about you, Katrín? You have worked on many Icelandic and Scandinavian crime fiction writers closely. Who are your favorite crime fiction writers in Iceland and in Scandinavia?

Jakobsdóttir: I enjoy nearly all crime fiction, but Agatha Christie, I really love her. I used to read Enid Blyton and the Nancy Drew books when I was a child, but Agatha Christie is the first crime fiction writer I read as a child; I finished all the children’s crime fiction in the public library in my neighborhood, and then the librarian said, Here, read some crime fiction in Icelandic, so I read Murder on the Orient Express in Icelandic translation, and I thought it was the best book I have ever read. Then I read everything that had been translated at the same time. A few years later, Ragnar began translating Christie’s novels as a teenager, so I read on. I don’t know why. Probably because my life is absolutely not interesting, so I always enjoyed reading about mysteries. But maybe because my life is very peaceful . . . I always think reading crime fiction is like going to a psychologist. You read about a problem, you wonder about the problem, the problem is solved, justice is done. You feel good, you feel comfort in your heart. Order has been established in your life— it’s a little bit like clearing your mind and the subconscious.

I always think reading crime fiction is like going to a psychologist. You read about a problem, you wonder about the problem, the problem is solved, justice is done. – Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Vanwesenbeeck: In Reykjavík, you fulfill this generic formula, but you also offer a sociopolitical critique along the way. I don’t know which of you had the pen moving on different chapters or characters, but, for instance, I can certainly see Ragnar-esque passages with the rookie detective and the bleak Viðey scenes, and then Sunna and the feminist undercurrent, especially her critique of the Reykjavík guy club and the corruption that persists from the 1950s to the ’80s, strike me as your pen, Katrín. So how did you end up reconciling your artistic, writerly sensibilities as you wrote the novel? Did you negotiate? Did you actually say things like, I want Sunna, a young comparative literature graduate student, to take over the investigation against a group of wealthy, powerful men?

Vanwesenbeeck: In Reykjavík, you fulfill this generic formula, but you also offer a sociopolitical critique along the way. I don’t know which of you had the pen moving on different chapters or characters, but, for instance, I can certainly see Ragnar-esque passages with the rookie detective and the bleak Viðey scenes, and then Sunna and the feminist undercurrent, especially her critique of the Reykjavík guy club and the corruption that persists from the 1950s to the ’80s, strike me as your pen, Katrín. So how did you end up reconciling your artistic, writerly sensibilities as you wrote the novel? Did you negotiate? Did you actually say things like, I want Sunna, a young comparative literature graduate student, to take over the investigation against a group of wealthy, powerful men?

Jakobsdóttir: We first fleshed out the synopsis, and then each of us wrote certain sections of the novel, but our goal was to make sure that people could not identify who wrote what.

Jónasson: I think our plan all along was to have the protagonist die in the middle of the book. There was no real discussion about who would replace him. It was just an obvious transition that it would be his sister, Sunna.

Jakobsdóttir: It was very important that it would not be a romantic partner who took over, so we did not want that to be the driving force or the motivation.

Vanwesenbeeck: Romance is minimal in the novel. That was intentional, then?

Jakobsdóttir: Romance is minimal, there is a feminist thread, and when it comes to artistic choices, because Ragnar is a well-established author, maybe it was a little bit of a challenge for him to have someone having opinions about the characters and plot in the process.

There is quite a bit of Christie in this novel, but it’s also a Scandinavian story. – Ragnar Jónasson

Jónasson: But it was also a lot of fun. There was never any serious argument, and I was always ready to compromise from the start because it was basically my decision to co-write, not the other way around. When I suggested that we do a book together, I knew this would be a co-written book that had something from both of us. In terms of the death of the main character in the middle, that is one way of playing with the formula because as a writer, you want to do something original every time and not repeat yourself. At least that’s important for me. That’s a plot twist you don’t see a lot of. You build up sympathy for the main character and then let him disappear. We had a lot of fun in a way. It was an interesting way to do it in our case. So yes, there is quite a bit of Christie in this novel, but it’s also a Scandinavian story. As Katrín said, we have quite a bit of feminism and—

Jakobsdóttir: —and a lot of darkness and weather also, like every Scandinavian crime novel. Also, this concept of a missing person, which is very Icelandic. We were also thinking, it’s not built on any true crime, but there have been real cases in Iceland where people have disappeared, so that was also an influential aspect of our decision.

Jónasson: Historically, there were probably many more disappearances than murders in the last century. There used to be very few murders, maybe one murder a year, but more people disappeared, and so that creates a more plausible storyline for an Icelandic setting. There can be so many reasons for disappearance, and people can just let themselves disappear.

Jakobsdóttir: Or drown in the ocean.

Jónasson: Or there can be an accident. It’s a dangerous country. As we know in the Highlands, the sea and the elements are very close, so yes. From the start, we also had the idea that this would be an epic story by telling the story of a thirty-year-old case. It’s only the first couple of chapters that deal with the early decades. The span of time gives it sort of an epic feeling that it’s more than just one case, the case of Lara, that it’s a generational mystery Valur is trying to solve when we get into the story.

Vanwesenbeeck: Maybe it’s a good moment to talk about space and setting. Berit Glanz analyzes the spatial traits of Icelandic texts and notes the important role of space starting with the Saga age. Ragnar, in your novels, we are used to seeing a very distinctive spatial aesthetics, a sense of space that can be both welcoming and hostile; a pervasive, romanticized darkness that you portray as quintessentially Icelandic. In this noir ethos, the capital city of Reykjavík, as the urban center of Iceland, is usually left behind by the characters or exists from a distance. How do the urban versus rural negotiations work in Icelandic crime fiction in general, and what is the spatial aesthetics in Reykjavík? Is Viðey the Siglufjordur of Reykjavík? Why did you decide on the title Reykjavík, while most of the mystery takes place on the small island of Viðey, for instance, at least in the beginning?

Jakobsdóttir: There is a simple explanation for that. It’s embarrassing, but it was the working title, and the reason for the working title was we were thinking about Reykjavík in 1986 because it was a big year for the city. It was the two hundredth anniversary of the city and the year of the Reagan–Gorbachev summit. We were getting very close to the date of publication, and the publisher asked what it was going to be called, and then it couldn’t really be called anything else.

Jónasson: We are happy with the title. Viðey is a part of Reykjavík for one, and the investigation takes place in Reykjavík, and the city is so much in the background because we are telling the story of this momentous year (1986), with the anniversary, summit, and everything in between. A small town is turning into a big city, so a lot of it takes place in Reykjavík.

Vanwesenbeeck: Reykjavík is in a way like another character in the novel, then.

Jónasson: It really is.

Jakobsdóttir: Also, during this time, in the 1980s, there was a new town center being built—actually, it never has become a real town center. But it is a phase that many cities had gone through. It was a really dynamic time for the city, and it has, like you said, become a sort of a character in the book.

Jónasson: It’s different from my other books. But also, this is a different venture, it’s a different story.

Vanwesenbeeck: I think we are all intrigued by space and how it’s used in crime fiction, especially Nordic noir. In Icelandic noir, Reykjavík exists in tandem with rural Iceland, typically a small town in the north. Here, Husavik, Valur, and Sunna are from a small town. What’s the importance of dichotomies of space in Icelandic noir? Does Reykjavík have a mythology of its own?

Jakobsdóttir: It does because many of the old crime novels bore the name Reykjavík in their titles. For example, Secrets of Reykjavík, which was published in the 1930s, also Everything Is Going Well in Reykjavík, also published in the 1930s. So Reykjavík was always a mythological character in crime novels because it was the place where everybody was corrupt and where you had the underworld and the lowlifes, whereas the rural areas of Iceland have always been—well, maybe not innocent—but innocent on the surface. Bad things can happen there too.

Jónasson: I think a lot of literature in the twentieth century in Iceland, not only books but films as well, has this underlying theme of the countryside versus the city. Reykjavík is such a young city—most of our parents are not really from Reykjavík, and even Katrín and I identify with some places in the north and the south because of our parents or grandparents. So, we don’t have a lot of people who identify as purely from Reykjavík.

Jakobsdóttir: I do. My grandparents and parents are from Reykjavík, and I am a parliamentarian for Reykjavík, so . . .

Jónasson: The city has been growing fast in the last couple of years, but before that people were spread all over the place.

Jakobsdóttir: It’s also interesting because in Iceland, the great majority of people live in and around Reykjavík. It’s like two-thirds of the population.

Jónasson: It’s been moving very fast in that direction, people moving from the rural areas to the city.

Jakobsdóttir: So, it’s a very important city for many people.

Vanwesenbeeck: Perhaps we can also touch upon the dichotomy between rural and urban. Valur and Sunna are originally from Husavik, and we get the sense that there are socioeconomic differences between people from Husavik and Reykjavík; inequalities and class differences. Is there a mythology of the north and of Reykjavík in Icelandic noir? I am wondering if this is a more pervasive motif that exists in Icelandic literature.

Jónasson: I think it is. Also, it’s easier to write about a place from the eyes of a newcomer or stranger. So, if you are writing about Reykjavík, it’s interesting to do it from the point of view of someone from a small town and vice versa.

It’s easier to write about a place from the eyes of a newcomer or stranger. – Ragnar Jónasson

Jakobsdóttir: Other writers have also written about the strain between Reykjavík and the rural areas in Iceland. I think it’s a thread you can find in many Icelandic writers and crime writers.

Vanwesenbeeck: Katrín, I’d like to follow up with a question about the nexus between Icelandic crime fiction and nationality. In your article “Meaningless Icelanders: Icelandic Crime Fiction and Nationality,” you note that “Icelandic literature is still pervaded by the sign system of nationality and the contrast between city and country.” Why do you think “nationality became one of the fundamental pillars of the genre,” and given the global appeal and marketing of the genre, is this sign system of nationality creating an exotic Iceland, or a “Tourist-Iceland” as you call it, for the global reader? Or is this meaningless but somber nationalism an existential crisis in Iceland that crime fiction merely tackles?

Jakobsdóttir: You were previously asking me about the bridge between academic and creative writing, so maybe this is the bridge for me. I wrote about national signifiers in Icelandic crime fiction, and I was very critical of them, but in this novel we were very conscious about flagging the national signifiers that can be found in many branches of popular culture. So, maybe it is like a symbolic gesture to this genre of popular culture, crime fiction, because in many crime novels you can find a picture of what we think of ourselves as a nation. From that perspective, there is loads of interesting stuff there.

Vanwesenbeeck: Let me connect that question about nationality to Reykjavík. The two-hundred-year anniversary of Reykjavík occupies a considerable role in the novel. The national celebrations, the unified nation behind this moment, are juxtaposed with the ghost of Lara in the story. But aside from the national historical milestones, there are so many cultural signifiers in the novel, some familiar and popular and some unknown to the English reader: Halldór Laxness, the introduction of television to Iceland in 1966, the new aluminum króna, Iceland’s naming laws, the Höfði Peace Summit, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, NATO’s base in Keflavik, Ingólfur Arnarson, whaling controversy, cocktail sauce (which Icelanders claim as their own), brauðterta. Do these denote a certain nostalgia for Icelandic readers, or do they summon a set of superficial signifiers to represent Iceland for the global readers? I wonder if in Iceland readers approach the novel and say, “Oh, you summon all the nostalgia for us of a bygone time”? Or is the novel summoning the national signifiers, the Cold War era, the 1980s for a global audience?

Jakobsdóttir: We wrote the book for an Icelandic audience. This was so much written for Icelanders that I am surprised that anybody outside of Iceland likes it.

Jónasson: Everything I write is for an Icelandic audience, and I think that’s the way it has to be. At least, if you are writing a book set in Iceland, published in Iceland, you have to be honest to your audience, the local audience first, so I think that’s what we did. But then we have a fantastic translation, and in the English translation, there is a bit of editing done—

Jakobsdóttir: —to explain a little bit what every Icelander would know—

Jónasson: —by removing some of the references that nobody would get, like names of local radio personalities.

Vanwesenbeeck: So, it’s adapted for the English audience.

Jónasson: A little bit.

Jakobsdóttir: Not a lot.

Jónasson: In that way, we definitely wrote it for the Icelandic audience because we did not check ourselves in any way. We used local references.

Vanwesenbeeck: And there is a little bit of nostalgia in those pop culture signifiers.

Jakobsdóttir: Yes, we were ten-year-olds in 1986, and if you had a relatively good childhood, you look back and everything is so much more rosy, so much better. So, what we did was remember this time from our hearts and memories but also write about it with the knowledge that we now have: back then we had this system of men controlling society, women being harassed.

Vanwesenbeeck: You have a great line about journalists in the novel: “Journalism is such a man’s world.”

Jakobsdóttir: It’s a new consciousness among grown-ups. But also, because memory is a tricky thing, you don’t really remember anything. You remember the feeling and emotions, so we were kind of transmitting those, but then of course, we went on the internet and looked up the newspapers and tried to make it as credible as possible.

Jónasson: You know, down to the detail of what the weather was like when Ronald Reagan arrived in Reykjavík. It was raining. The order of events, who came out of the house first after the summit.

Jakobsdóttir: Which movies were in the cinemas and also just certain details . . .

Jónasson: So, it originally came from our own memories, but we checked the details afterward. The radio, the summit, the anniversary are things we remember very vividly even though we do not have all the details, so we looked them up.

Jakobsdóttir: I was in downtown Reykjavík during the anniversary, and I got a bite of the cake, and I remember the taste of it and saying, “Oh, alcohol,” because there was sherry in the cake, and we looked that up and there was sherry in the cake.

Vanwesenbeeck: Is it fair to say that you were deliberate about the pop culture details/signifiers in the book?

Jónasson: Yes, because it was nostalgic for us, the book was partly written for our own pleasure.

Jakobsdóttir: Not partly, mainly for our own pleasure. At least in my case, because Ragnar is writing books all the time. I haven’t done it before, and I don’t know if I’ll ever do it again.

Vanwesenbeeck: That was a question I had for later, but maybe I’ll ask it now. Is there a sequel to Reykjavík?

Jakobsdóttir: We will answer that differently. I will say no, and Ragnar will say yes.

Vanwesenbeeck: Sunna is such a distinctive protagonist. She gets a degree in comparative literature in the 1980s, so I thought maybe a sequel with her is in the making?

Jónasson: It’s undecided, but it’s also mostly up to Katrín because of her lack of time. But in general, we’d love to write another book about Sunna. She is a lovely character. That was the plan all along, to have Valur and Sunna as the central characters. But Sunna is the one standing at the end of the novel, and I think we are fond of her character. Wouldn’t you say, Katrín?

I was so surprised because I had never written a novel and had no idea how attached you become to the characters. – Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Jakobsdóttir: I was so surprised because I had never written a novel and had no idea how attached you become to the characters. I thought that was really odd because in my day job I regard myself as a distant and sometimes cynical person, you know, so I thought it’d be the same here, but I was completely and emotionally related to these characters. I don’t know if this is a correct description of myself—probably not—but I actually thought I’d be like, this is a nice book we are writing and I won’t really have any feelings connected to it, but I was wrong.

Jónasson: Sunna is very much alive.

Jakobsdóttir: Yes, all the characters are.

Jónasson: And we think, What is she going to do next, what will she be doing in two years’ time?

Vanwesenbeeck: As a reader, I was completely immersed in Sunna’s character and was glad that Kristjan, the rookie police officer, disappeared and the investigation was handed over to Sunna.

Jónasson: I don’t really like police procedurals. Sometimes if you write crime fiction, you are stuck with the police.

Jakobsdóttir: Amateur detectives are complicated, but that’s also an Agatha Christie reference, I think.

Jónasson: Yes, it is. Sunna is like an amateur detective. We got away with it, I think, for this book, and it’s hard to get away with it in contemporary literature. I was happy we managed to have an amateur detective solve the murder. So, the challenge in the next book will be, Is she a journalist? Is she still a complete amateur? If she’s a journalist, that’s more of a traditional thing, but maybe she is writing poetry. But last week, they found a skull in Katrín’s office.

Jakobsdóttir: Ragnar wants us to write a book about that.

Vanwesenbeeck: You mean archaeological excavations revealed a skull in Katrín’s office?

Jakobsdóttir: No, they were removing a floor panel in my office for renovations, so now we are analyzing the skull.

Jónasson: So, that must be the next book, the start of the book, and we will see what happens. Reality versus fiction.

Vanwesenbeeck: Is that a potential collaboration?

Jakobsdóttir: No, let’s just stay calm. I have a very busy job.

Vanwesenbeeck: Fair enough. Let’s talk about translation. Iceland is a nation of avid readers and home to a rather busy translation traffic. Actually, other than being writers, you are both translators. Ragnar, you translated various Agatha Christie novels into Icelandic. How closely do you work with your translator, and how protective are you of the original Icelandic text? Do you leave the text in the hands of Victoria Cribb, or are you involved in the process as a translator?

Jónasson: You have to trust your translator, but also, for a language you speak, write, and read, you need to make sure that the translation gets the tone of the book correctly. In our case, it’s always a lovely collaboration with Vicky.

Jakobsdóttir: I have also read the first couple of pages in French translation, and it looks quite good, too. But it’s always a different experience to read a book in another language.

Jónasson: And it’s fun.

Vanwesenbeeck: Icelandic can be stylistically so creative. Does it matter to you that these nuances get translated?

Jakobsdóttir: I think our book is relatively easy to translate. I think in style it’s not so complicated.

Jónasson: I still think that when I read Scandinavian books translated into English, it is a difficult job to do well, whether it’s crime fiction or something else. When you read a Swedish or Norwegian book in Icelandic versus an English translation, the Icelandic translation gets it better because the languages are closer and you get the tone better in a Nordic translation. If you don’t get the tone right, the translation doesn’t work, and that’s what Vicky does so well. Every time I read Victoria’s translation, I say, she really got it.

Vanwesenbeeck: Ragnar, I’d like to segue into the Iceland Noir Literary Festival that you and Yrsa Sigurðardóttir started in Iceland in 2013 and takes place in Iceland every November. How has the festival affected the growth of crime fiction writing in Iceland and the marketing of Icelandic noir in the world book market?

Jónasson: I don’t know. I think the authors were doing a good job already, but hopefully we helped, and I know quite a few writers, not only crime fiction writers but fiction writers in general, who found literary agents through the festival. We have literary agents and journalists at the festival, so I think it’s helped to the extent it can. That was the whole point, to get Icelandic literature across and promote it and, second, to get interesting authors to come and visit Iceland. The problem is that Icelanders buy tickets to events very late, so in the past, tickets were sold out to traveling guests who made up most of the attendees and not many locals attended, but this year we have a fifty/fifty audience of local versus international guests, and that’s fantastic. It’s working both ways: we are promoting Icelandic authors to the international audience, and we have international authors come.

Vanwesenbeeck: This was a pleasure. Thank you so much for your time, and best wishes with this year’s Iceland Noir Festival and Reykjavík.

September 2023

Editorial note: For more on Icelandic noir, see J. Madison Davis, “Murder in a Cold and Peaceful Place,” WLT, Nov. 2009, 9–11.