History Looms Large over the Gaelic Athletic Association

What are the three ancient Irish sports and how have they played a role in Irish history? Find out this and more in Mraović-O’Hare’s short essay.

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) is an Irish sports organization that fosters Irish identity, language, and heritage. It is also an integral part of recent Irish history. The GAA was founded in 1884 when a group of seven Irishmen decided to form a body that would promote and preserve traditional Irish games and activities as well as make sports accessible to the common people. At that time, sports were a privilege mostly reserved for the British elite and aristocracy; until 1922, Ireland was a part of the British Empire and sports like cricket, rugby, and soccer were practiced by clubs that favored the British. Michael Cusack, one of the GAA founders, was paradoxically immortalized by James Joyce: Cusack inspired the Citizen in Ulysses’ chapter “Cyclops.” Though Joyce, who favored Europeanism and modernist intellectualism, used the Citizen to satirize the Gaelic revival. His Citizen is a staunch nationalist and an anti-Semite who in jest throws a biscuit tin at the protagonist, Leopold Bloom, after Bloom reminds him that Jesus was a Jew.

Michael Cusack, one of the GAA founders, was paradoxically immortalized by James Joyce.

The GAA includes three ancient Irish sports: handball, hurling, and football. Handball, first played by the Celts and the least popular of the three sports, resembles squash, but the ball is hit by a bare hand against a wall. Hurling is considered the oldest Irish game, and I heard many GAA members proudly emphasize that the Irish were playing it around three thousand years ago, when the pyramids were being built. In Irish folklore and mythology, hurling is presented as a preparation for battle; a demigod and mythological hero, Cú Chulainn, plays hurling in the Irish epic The Táin, set in the first century bce. Played with a stick and a small hard ball, it is thought to be the fastest game in the world and extremely dangerous. Hurling players do not wear protective gear except helmets, but there was a widespread uproar when helmets were made mandatory in 2010. The fans thought the game would be compromised, and the players identified the helmets with athletic flaws. However, football, which can be described as a combination of soccer and rugby, is the most popular sport in Ireland. Every year, the final game at Croke Park in Dublin draws more than eighty thousand spectators.

Physical and fast, football can be traced to the fourteenth century but is most obviously associated with Irish modern history. During the Irish war of independence, in 1920, British soldiers, unprovoked, opened fire at the spectators and players in Croke Park, killing fourteen civilians and wounding sixty. The action was a retaliation for the IRA murdering fifteen undercover British agents that day on orders of Michael Collins, who tried to eliminate the intelligence network in Dublin. Among the victims was the player Michael Mick Hogan; a stand at Croke Park was named after him only four years following his death. The event that is known as the first Irish Bloody Sunday further solidified resistance toward the British and significantly contributed to the declaration of Irish independence two years later. (U2 sings about another Bloody Sunday, which happened in 1972 Belfast.)

Therefore, not surprisingly, Gaelic football is the second most popular sport in Northern Ireland (first being soccer); its national and cultural significance seems to be even more obvious in the region that was until twenty-five years ago marred by the political and religious conflict known as the Troubles. According to a Relatives for Justice (RFJ) study, 156 people associated with the GAA died during the Troubles; almost half of those were killed by loyalist paramilitaries, while nine of the twenty-three H-block hunger strikers were GAA members. Until 2001, members of the British military forces were not allowed to join the GAA. The rule was established in 1897, when it was suspected that the Royal Irish Constabulary was trying to infiltrate the GAA in an attempt to thwart the Irish fight for independence. Similarly, GAA members were banned according to rule 27, which was not abolished until 1971, from playing or watching “imported” games, especially soccer, rugby, cricket, and hockey. The GAA also insists on using its fields and facilities exclusively for their own games and activities, with few exceptions: since 2007, Croke Park has begun hosting concerts and other sports, such as rugby, while county grounds were allowed only four years ago to be used for non-GAA events on a “case-by-case basis.”

The GAA functions as a family-oriented social club. A player in a Dublin GAA recently explained, “You don’t choose your GAA club; you’re born into it.” GAA members are expected to join the closest club to their home and be loyal to it, even though nowadays the organization is tolerant to changes caused by the dictates of modern life and employment. It is not uncommon for multiple generations to belong to the same club, their membership extending for decades. However, probably the most impressive element of the GAA is its amateur status. The players are not compensated, all of them have regular jobs, and yet playing is extremely competitive. Upholding the ethics of volunteering and equality, the GAA prohibits payment of players, allowing only compensation in occasional sports gear or travel reimbursement costs. (The GAA receives grants from the government but is mostly a self-serving enterprise that funnels money back into the organization.)

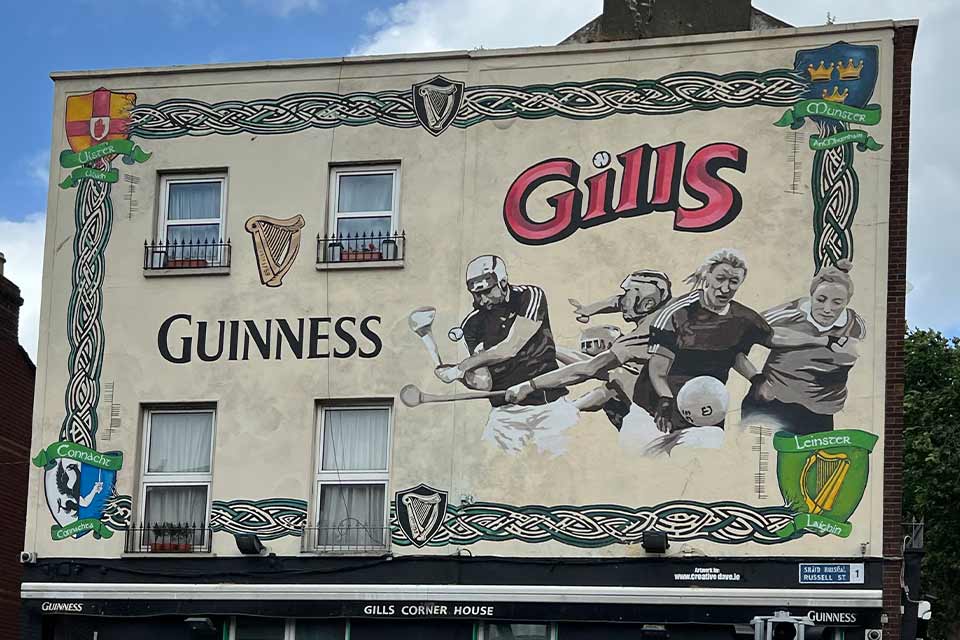

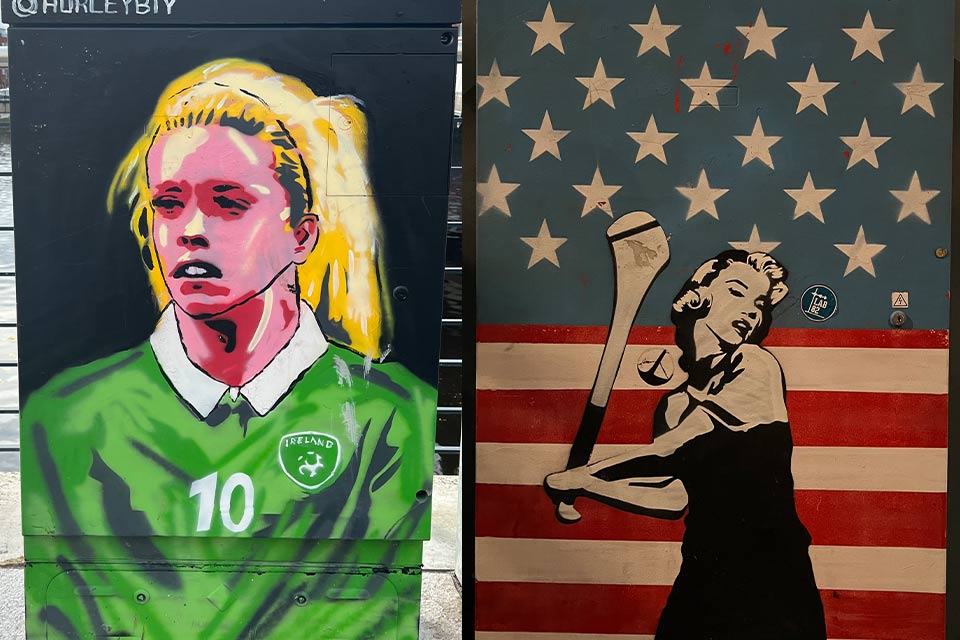

GAA players, in particular football players and hurlers, are celebrities in Ireland and considered national heroes. Male competitors have been presented in painting and sculpture in heroic poses that evoke endurance and overcoming hardships. The Tipperary Hurler (1928), by Seán Keating, is possibly the most famous art piece that contributes to the Irish national narrative: the hurler is pensive yet strong and ready to use the stick that he clenches with both hands while it rests on his lap. The stadiums are also named after prominent GAA players, creating unique national memorials.

The opposing fans share sections, good-naturedly engage in repartee, and spontaneously regulate any potentially disruptive supporters.

Such commemorative spaces have an unofficial code of behavior. Thanks to my husband and son, I have been at many sporting events, from American NHL to Premier League soccer games, but the camaraderie and tolerance of the GAA fans I have encountered is unsurpassed. The opposing fans share sections, good-naturedly engage in repartee, and spontaneously regulate any potentially disruptive supporters. One-third of the audience seems to be children; their tickets are five euros (six dollars). But when a scuffle indeed broke out in a separate standing section this July, and many people were arrested during a dramatic All-Ireland football quarterfinal between the rivals Armagh and Monaghan at Croke Park, it was national news for days. The GAA immediately condemned the fight as “unacceptable,” while the Irish News wrote that “women and children also . . . witnessed violent scenes.” Though those around us, even with children, were not too fazed by the conflict of the die-hard supporters, the media raged against the behavior they found shocking, invoking traditional values and the national importance of the GAA.

The history looms large, and demands respect.

Jefferson City, Tennessee