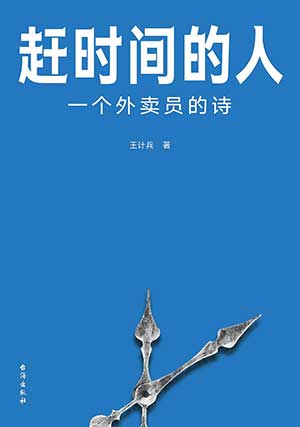

Gan Shijian De Ren (A Man in a Hurry) by Wang Jibing

Beijing. Tai Hai. 2023. 288 pages.

Beijing. Tai Hai. 2023. 288 pages.

Poet Wang Jibing is one of the representative figures in China’s contemporary new workers’ literature (see WLT, Spring 2021, 28). Initially an ordinary farmer from Jiangsu province, he used to work as a deliveryman. He has had a strong interest in literature since his youth, but because he grew up in the countryside, no one around him could understand his pursuit of literature and even thought that his devotion to literary creation was somewhat abnormal. His father destroyed his draft of a 200,000-word novel. Without the support of his family, Wang Jibing had to give up his literary dream and began to work in the city, taking a path similar to that of most rural youth. When he was nearly fifty, he began publishing his poems online, which drew attention from readers and led to the publication of this influential collection of poems, A Man in a Hurry, in 2023.

New workers’ literature is a new type of proletarian literature that has emerged in China since 2000, taking the working class as its creative object. Compared with earlier proletarian literature, new workers’ literature has two distinctive features: first, the authors of new workers’ literature come from the workers’ groups, especially the migrant workers who migrate to the cities for work; second, the new workers’ literature downplays the traditional theme of the liberation of the working class and instead shows two different kinds of consciousness of the new working class: one expresses the cruelty and despair of the underclass, and the other insists on defending the life and dignity of the underclass.

The former is represented by the poet Xu Lizhi. For example, his poem “I Swallowed a Moon Made of Iron” expresses the boredom and despair of Chinese workers toward the industrial life constructed by “iron” and “industrial wastewater.” Ultimately, the “I” in the poem decides to rebel against this life, and “what I once swallowed is now gushing out from my throat.” Xu chose to commit suicide to end his alienated lower-class factory life.

Fan Yusu, Chen Nianxi, and Wang Jibing represent the latter tradition. Though their writing is different in style, they all write about the toughness of the will to face suffering. The protagonists of Nanny Fan Yusu’s nonfiction works are mostly talented characters from the lower class. However, due to their origins, they cannot develop their talents even after lifelong suffering, and most end up in poverty and depression. The works of Chen Nianxi, a miner, are more about the people at the bottom of the ladder, who are strong, unyielding, and struggling to survive for the sake of their families. Wang Jibing’s work is most similar to Chen’s in that it shows love and care for the lives of the underclass and the defense of their dignity.

However, there are noticeable differences between the two. First, Chen Nianxi’s works portray mostly heroes of the lower class. He pays attention to those strong people at the bottom who are rich in the spirit of struggle and sacrifice. On the other hand, in Wang Jibing’s works, he mostly finds solemn beauty in the most ordinary people at the bottom. For example, in his poem “She’s So Like My Sister,” he writes that the sunlight shines on the faces of the cleaners in the morning, which he compares to the sunlight shining on the trenches. By juxtaposing the trenches with the wrinkles on the faces of the cleaners, Wang illuminates the sense of value and sanctity in the ordinary cleaners from a perspective that no one has ever imagined.

Second, Chen Nianxi, facing the fate of being at the bottom of the hierarchy, always has an unyielding spirit of fighting against fate, and his works reveal a sense of sadness that he knows he cannot do anything about it, yet he still chooses to struggle. Wang Jibing’s works can also be read in this sense of sadness, but his poems have a touch of traditional Chinese Buddhist thought, which provides a utopian vision of class relations in his works. He tries to resolve class conflicts in his poems through “cibei,” a Chinese philosophical idea with solid Buddhist overtones. Similar to the idea of compassion, cibei means to comfort all beings and relieve their suffering. He interpreted the suffering of the lower classes as a kind of compassionate sacrifice. In his poem titled “Cibei,” he suggests that “for human beings, cows and sheep are compassionate; for cows and sheep, grass and trees are compassionate,” transforming the suffering that the lower class endured into the compassion of the lower class for all beings. Instead of pointing a finger at the upper class and adopting violent and radical confrontation, Wang celebrates the people of the lower class who sacrificed themselves with compassion, using the gentlest words and phrases to try to arouse people’s conscience about the effects of class stratification.

Wang’s poems suffer from the same problem as many other new workers’ literature, namely, the moral romanticization of the underclass. However, the value of new workers’ literature lies in the fact that we can hear voices that genuinely originate from the bottom who have long been ignored, distorted, and even stigmatized. Society lacks works such as those created by Wang Jibing that show the beauty and dignity of the working class.

Zhang Wenru

China University of Petroleum, Beijing