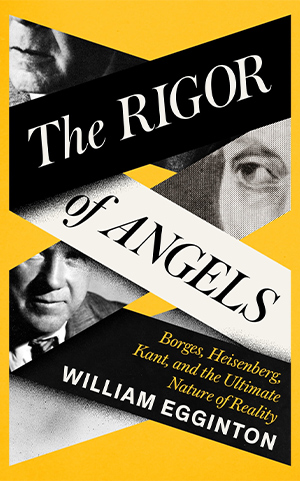

The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality by William Egginton

New York. Pantheon. 2023. 368 pages.

New York. Pantheon. 2023. 368 pages.

At first glance, the thinkers spotlighted in William Egginton’s book don’t necessarily belong together. Immanuel Kant, Jorge Luis Borges, and Werner Heisenberg worked in different fields, and the latter two made their breakthroughs more than a century after Kant’s death. But for Egginton, a prolific author of books on ethics, literary theory, and identity politics, such differences are secondary to the unlikely trio’s shared sense of purpose. The Rigor of Angels—the title paraphrases a line from Borges’s story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”—is a heady but accessible consideration of the question that fueled each man’s labors, a line of inquiry that underpins all others: Is the human mind capable of understanding the full scope of reality?

Egginton, in a bracing formulation, argues that his subjects’ achievements were informed by a degree of intellectual modesty. Heisenberg’s development of quantum theory, which helps explain how tiny particles move; Borges’s fictions about multiple worlds and vast repositories of information; Kant’s foundational exploration of free will and “the sublime,” which Egginton defines in part as “the awe we succumb to when we face the inconceivable mathematics of the cosmos”—each is an acknowledgment that there will always be mysteries science and art cannot decode. Summarizing Borges’s grim worldview, Egginton writes that “consciousness and identity” are but “a desperate illusion veiling an existential void.”

The book’s complex ideas are interspersed with memorable anecdotes about its subjects’ personal lives and examinations of their ethical failures. Borges burrowed into the abyss after a romance went sour, and his mood didn’t improve when, in 1936, he published a book that sold fewer than forty copies. Kant, who had particular ideas about men’s clothes, walked Prussian streets wearing a decorative sword. The book also benefits from Egginton’s discussion of the Argentine Borges’s perplexing decision to accept an award from Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, and of Heisenberg’s role as a scientist for the Nazis. Heisenberg later suggested that even if Hitler’s regime had the means and time to do so, his moral beliefs would’ve prevented him from building a nuclear bomb for Germany. It was a contention that many Americans found disgraceful, coming as it did from someone who, as one US scientist said, “worked for the cause of Himmler and Auschwitz.”

In a funny aside, Egginton recalls that a professor of his once lamented the staying power of Kant’s ideas, which, though compelling, are very difficult to describe. Heisenberg’s are even tougher to simplify, and Borges, for his part, can be plenty abstruse. But Egginton has a gift for distillation, and his admirable book helps us understand what’s at stake in some of the knottiest intellectual puzzles of the last three centuries.

Kevin Canfield

New York