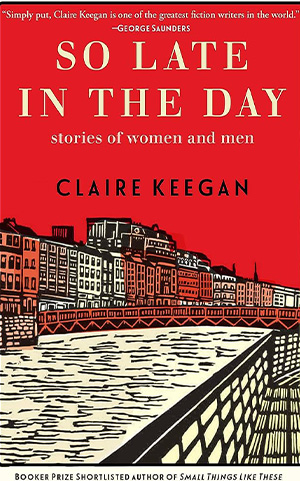

So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men by Claire Keegan

New York. Grove Press. 2023. 47 pages.

New York. Grove Press. 2023. 47 pages.

The Irish writer Claire Keegan is one of the most significant story writers in the English language. In her native country, she is considered a national treasure: with only two published collections of stories and three short stories issued as stand-alone books in almost twenty-five years, she has collected acknowledgments that range from the Rooney Prize to an Oscar nomination. Keegan’s Small Things Like These (2021), about a Magdalene laundry–like institution in a southeast Irish town, was the shortest text ever shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

In the manner of Foster (2010), first printed as a short story in the New Yorker and then extended into an independent volume, the latest Keegan book, So Late in the Day, was originally published under the title “Misogyny” in France and afterward in the New Yorker. The small book format of not even fifty pages contains a narrative that, according to Keegan, started as an exercise in her creative writing class about a decade ago. To demonstrate the ways in which fiction can be tense but not dramatic, she devised on a board a story about a man who goes home from work on a Friday afternoon and encounters things that are dramatic triggers but only for him. So Late in the Day opens on a hot afternoon of July 29 in a contemporary Dublin office on Merrion Square. Cathal, who is writing rejection letters to grant applicants, is ill at ease and so is everybody around him. The gloom is palpable: Cathal is unfocused and refuses to check his phone messages, while his coworkers, including his much younger boss, are gentle and restrained in their interactions with him. It seems death is looming.

However, through a series of flashbacks and foreshadowing, it is revealed that Cathal mourns what could have been—his (marital) happiness—and that, in a turn typical of Keegan, he is not deserving of the reader’s sympathy. Cathal was in a relationship with Sabine, who was French, generous with her time, energy, and money in particular, which repulsed him although he was physically attracted to her. His marriage proposal was a veiled business transaction that Sabine accepted after prolonged convincing, but the turning point of their relationship was Sabine’s impulsive decision to buy supposedly overpriced cherries for a pie. Since she didn’t have her wallet, Cathal felt forced to spend an equivalent of seven dollars. Later, he found the pie unappetizing and, more significantly, was appalled by Sabine’s spendthriftiness. He, of course, let her know that. And yet, despite his emotional and financial tightness, Cathal saw in Sabine a woman who would obliterate his loneliness.

As always in her writing, Keegan’s discussion of social and political issues is disguised by her focus on the mundane, while her reductive and elegant style is reminiscent of the rhythm of James Joyce and the melancholy humor of Anton Chekhov. Suggestively, one of the background characters is engrossed in Roddy Doyle’s The Woman Who Walked into Doors (1996), a novel about a physically and mentally abused wife who reclaims her life. Doyle’s novel was so well received that it was even developed into a miniseries and an opera. However, Keegan’s Cathal is oblivious to its cultural importance. Instead, he represents a masterful exploration of misogyny in the contemporary world.

Damjana Mraović-O’Hare

Carson-Newman University