Waiting for Wovoka: Envoys of Good Cheer and Liberty by Gerald Vizenor

Middletown, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2023. 109 pages.

Middletown, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2023. 109 pages.

The prolific author of more than forty works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry since 1961, recipient of the 2022 Mark Twain Award, and honorary curator of the American Haiku Archives since 2021, Gerald Vizenor inscribes Waiting for Wovoka into a recent series of novels that focus on the natural motions and cultural transformations which have accompanied the political and cultural encounters between the Anishinaabeg and the American authorities through the main events of World Wars I and II and their aftermath.

Blue Ravens (2014) took White Earth Reservation brothers Basile and Aloysius Beaulieu into trench warfare on the Western Front. Aloysius, inspired by Native prison ledger paintings, drew blue ravens on the skyline of Paris, echoing the revolutionary postwar mood. In Native

Tributes (2018), the two brothers and a veteran nurse, By Now Rose Beaulieu, returned to White Earth and joined in the puppet parleys held there in reaction to the predatory culture of the mission school. The group then participated in the Bonus March of 1932. Satie on the Seine (2020) brought Basile, Aloysius, and By Now Rose back to Paris with puppetry to denounce the horrors of wartime Nazism.

In Waiting for Wovoka, native stowaways perform puppet parleys at the “Theater of Chance” with the three veterans who have returned to White Earth. The group travels to the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle, Washington. After attending a performance of Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot at the fair, they improvise puppet parleys with the Ghost Dance, a counterpart to the endless waiting of Beckett’s play. The novel ends with the arrival of Parisian gallery owner Nathan Crémieux, a longtime friend of Basile and Aloysius.

Such a tight-woven, cross-cultural set of characters buttresses the creative motion of the storyline. A fire that ravaged the library triggers a reinvention of the classics in haikulike pronouncements that prolong Aristotle, Montaigne, Puccini, and Romain Rolland. In turn, the puppet parleys match historical characters who never met in real life, such as Gertrude Stein and Hitler, Aristotle and James Baldwin, Mother Jones and Andrew Carnegie, Samuel Beckett and Sitting Bull, or Rachel Carson and a bald eagle. They move the affirmation of Native identity from monologues to “an ironic play of characters in a native story” featuring actual quotations.

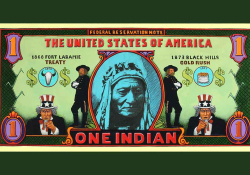

Thus, stories become literary transmotion, “creative or visionary literary motion, the motion of oral stories, the motion of trickster stories.” Their linguistic en abîme effect highlights “the chancy art of resistance.” The puppet parleys become the source of survivance and solidarity. A fluid escape from pain, they are a safe place where the gains and losses of tradition and adaptation can be fully examined. Is the teasing of new stories enough to offer hope and healing? Yes, says Vizenor, except for the enduring colonial demands for Native authenticity (the “myth of the good savage” of victimry) or for total assimilation into a scientific and chemical civilization.

Adaptability is the hallmark of human encounters. The coercive language at federal boarding schools, Vizenor emphasized in 1992, not only carried stories of “endurance and tribal spiritual restoration” but became “the creative literature of crossblood writers in the cities.” As the troupe travels in a converted school bus to Seattle, stopping at Native museums and reservations, a host of secondary characters gather around them, outcasts who unite in the wait for the elusive prophet Wovoka who, they realize with ironic surprise, carries the same “elusive sense of cultural absence” as Beckett’s play.

These four novels are a masterful foray into a new language of Native novelists and poets, a “literary ghost dance, a literature of liberation that enlivens tribal survivance.” In turns poignant and ironic, Waiting for Wovoka suffuses a profound humanism.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin