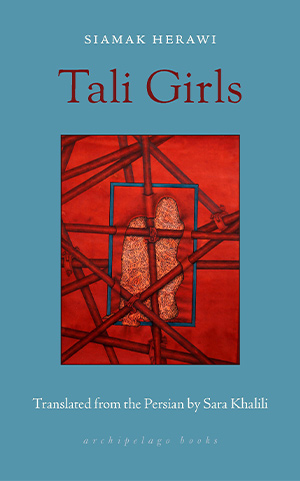

Tali Girls: A Novel of Afghanistan by Siamak Herawi

New York. Archipelago Books. 2023. 340 pages.

New York. Archipelago Books. 2023. 340 pages.

Tali Girls, Afghan author Siamak Herawi’s first novel to be translated into English (melodically, by Sara Khalili), is a propulsive and sprawling debut. At the heart of Tali Girls is Kowsar.

When the novel opens, Kowsar is a child, and her world is enchanted. Her family’s house in the Afghan village of Tali rests on one side of a valley, next to a riverbank. “Our valley is green and lush,” Kowsar says, “drunk with springs, waterfalls, and streams that intricately weave their way to where they meet and create a roaring mountain river.” At night, the moon showers this river in its “creamy glow,” while frogs and crickets sing, and “poplars’ leaves sway like dangling earrings.” Outsiders from the nearby provincial capital of Qala-e-Naw call Tali “heaven,” imagining that modernity’s sullying fingers have yet to touch the valley. It is shortly after the US invasion of Afghanistan, and there is no electricity, television, or education for the children in Tali. But then, in 2006, the government sends funds to build a school in the mountainous community, which is to change the course of Kowsar’s life.

It is immediately apparent that Kowsar is a prodigy. She has a photographic memory and is elated by the process of learning. Hungry for knowledge of the world around her, she memorizes entire textbooks in mere weeks and can recite the poetry of Hanzalah Badghisi after hearing the local poet’s verses just once. Kowsar is unique in other, more grim ways, too. She suffers from convulsive syncope, moments when she goes out of her body or loses consciousness due to overwhelming emotion. To herself, Kowsar thinks of this as “going gray,” a time when her world drains of color.

Indeed, there are many dark moments in Tali Girls. As Kowsar grows older, the town around her begins to change; heaven turns to hell. The Taliban arrive in the area and burn the school to the ground. The liberal schoolteachers are publicly humiliated for “corrupting and perverting children”—that is, for teaching them to read. The Taliban (partnering strategically with the provincial government) strongarm the people of Tali into replacing their traditional crops of wheat, peas, and mung beans with the more profitable cash crop of opium. Soon, many young men in the community become addicted to the drug, their speech slowed and their once-muscular bodies turned frail. Kowsar is saddened to see them and thinks to herself that the village youth are like “black skeletons in the hands of the wind, the poppy farms soon to be their graveyard.”

Suffering is particularly acute for the women and girls of Tali. One of Kowsar’s friends, the beautiful Simin, is married off at nine years old to a lecherous older man to save her family from destitution (I hate this fetid silo of filth, Simin thinks to herself of her new husband’s home). Another young woman, Geesu, faces an impossible decision after a Talib militant fires off a round of bullets outside of her father’s house, shouting, “Geesu is mine!”—his way of forcing his claim to her hand in marriage. As time goes on, women are forced to be more and more careful about how they dress, where they go in public, and what they say. Against the twenty-year US occupation of Afghanistan and the gradual Taliban takeover of the country, the novel follows Kowsar and her friends (and their mothers, aunts, and female relations-in-law) as they navigate the loaded subject of marriage and the changing roles of women in society.

Although Kowsar is at the core of Tali Girls, the story is not limited to her perspective. As the novel progresses, Kowsar’s first-person narration balloons and bursts, bringing the reader into the minds and memories of other people in Tali. The format is not cyclical; there is no rotation through a set of established voices. Rather, the change in narrator is more like a relay race–one person’s story leads to the next, sometimes lasting a whole chapter, and other times fragmenting between multiple perspectives within one section.

This multiplicity of viewpoints could be a means of illustrating the diversity of Afghan society itself. As Kowsar’s schoolteacher tells her, in Afghanistan, “we have people of every creed and color. Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmens, and Pashtuns” (and Hazaras, Aimaqs, Nuristanis, Baluchis, and others, this reviewer might add). The main problem facing the nation, in the teacher’s eyes, are “outsiders and inciters,” people who rupture the safety and security of the Afghan people, preventing the country from “flourish[ing] into a blooming orchard.”

The teacher’s theory about the thwarted cosmopolitanism of Afghan society is one among many in this heteroglossic novel; each character seems to nurse their own conviction about the country’s current situation. Tali Girls does not, however, aim to provide a comprehensive or “balanced” account of the different perspectives within Afghanistan. In the novel, there are clear villains and victims. Suffice to say, the Taliban and their government cronies do not leave a favorable impression.

Tali Girls is Herawi’s tenth published book and his sixth novel in the last ten years. His stories often speak directly to current events in Afghanistan, focusing on how ordinary Afghans have weathered the ongoing storm of suicide attacks, war, corruption, and tensions between ethnic groups in the country. In Tali Girls, the central problem facing the villagers comes down to this: to leave or to stay. As one young man from Tali describes his impossible situation, “Running away is worse than staying, and staying is worse than running away.”

It would be easy to conclude that the people of Tali are doomed to continue “living in limbo,” hovering between two imperfect options. But Tali Girls is too big-hearted to remain in this space of cynicism. Throughout the book, sentiments of hopelessness and despair are always contradicted by the fierce spirit of Kowsar, with her belief in the power of love, and of storytelling.

Anna Learn

University of Washington, Seattle