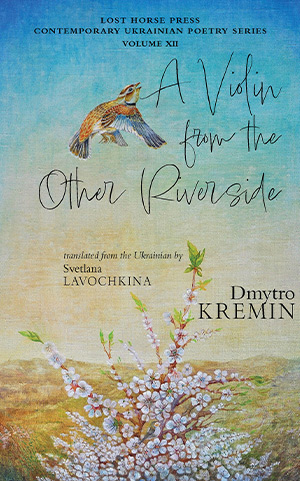

A Violin from the Other Riverside by Dmytro Kremin

Liberty Lake, Washington. Lost Horse Press. 2023. 215 pages.

Liberty Lake, Washington. Lost Horse Press. 2023. 215 pages.

Dmytro Kremin’s A Violin from the Other Riverside arrives in a dual-language edition at a critical time in Ukrainian history and the Ukrainian language. Described as a “philosophical bow strung with a Ukrainian timeline arrow,” its timeline spans some of the most forgotten eras in Ukrainian and European history. From the Pontic steppes to Scythia, ancient Greece, Rome, and into the modern era when Russian occupiers illegally enter Ukraine’s territory, these passionate poems guide readers through epics and dramas both universal and personal with wise notes that illuminate Ukraine’s current struggle for independence.

“Elegy of the Years on Fire” alludes to the 2014 Maidan events that set the political stage for the 2022 invasion. Opening with the stark, prophetic line “When Kyiv is beset with guns and smoke,” the poem segues into images rife with war. “Blood-spattered mists” hang heavily, and the poem’s speaker stands in disbelief, weighed down by a soul “filled with longing.” However, the Ukrainian resilience that, for nearly two years, has awed the globe is fully displayed in one of the poem’s most memorable stanzas. In it, the concept of victory becomes a “last frontier,” where pagan gods like Perun and Striborg abide among modern mortals.

The mythical pagan gods are not the only Ukrainian historical figures invited into Kremin’s verses. The famous outlaw Oleksa Dovbush, a folk hero often compared to Robin Hood, finds his place in “A Carpathian Souvenir.” The speaker declares that Dovbush “is no more” and that “no one like him will ever live.” Dovbush’s passing, however, is more than the death of a revered folk hero. Kremin portrays it as a catalyst, one that spurs the irreversible trend of cultural erasure, particularly for the Hutsuls. Their cultural and artistic remnants become cheap commodities in a society which does not understand or appreciate the remnants’ significance. The speaker laments:

The eagles flew into all shops,

perched on the shelves in every teahouse, every inn,

They carried prison smells on their wings,

Which stretched from hamlets to our metropolis.

The whining of a two-man saw, the screeching of an ax

Lived in the genes of pines and beeches.

And those were trees without age rings . . .

As the poem continues, the speaker captures other snippets of the persecution of Ukrainian culture and language. Other historical figures like bard Ihor Bilozir, a renowned Ukrainian singer and composer fatally wounded for singing in Ukrainian, also appear. The speaker portrays Bilozir’s persecution bluntly:

Blood circulates in names and words.

Bard Ihor Bilozir was murdered

For singing in Ukrainian.

The eagle squawks . . . It went as far

as Lviv.

For readers unfamiliar with Ukrainian geography and politics, Lviv—the largest city in western Ukraine—is a cultural, multiethnic, and historic city where the Ukrainian language has always thrived despite efforts to oppress it. The speaker’s blunt, forthright tone drips with brutal honesty regarding the historical and contemporary Soviet influence in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, Kremin’s poetry is not entirely draped with historical allusions and sociopolitical commentary. At times, his verses point readers in a refreshing, Romantic direction. “Only you . . . For you, the cuckoo sings” is one of the collection’s more sentimental gems. Minimalist in both form and language, the poem utilizes brief lines and ellipses to create a dreamlike sensation:

Only you . . .

Look back into the past,

Don’t willow-stoop in sadness.

Only you . . .

The two of us are one.

While the repetition reiterates the speaker’s devotion to the mysterious “you,” it is the poem’s final lines that emotionally clinch the piece into place: “And if a single tear should fall, / We’ll split the salty drop in two.” The repetition of the words “you” and “two” create an internal rhyme that transcends into the cyclical, which—despite the poem’s simplicity—forms an emotional chaos that easily ensnares readers.

In the translator’s note included at the collection’s beginning, Svetlana Lavochkina writes: “Kremin means ‘flint’ in Ukrainian. It is the poet’s real family name, not a pseudonym. Flint: a fire starter, a hunting spear tip, a blade—all precise metaphors for Kremin’s work.” Lavochkina’s description adeptly captures the sharpness of not only Kremin’s poetic structures and language but also the historical portrayals and philosophical proposals inherent in Kremin’s work. Reading through this collection is like making a trip through history and meeting heroes and underdogs, folk figures and legends, which will spark not only readers’ imaginations but also an awareness of Ukraine’s ancient and more recent histories. Initially, readers—particularly Western ones—may stand at the edges of history, place, and lore and gaze confusedly, maybe even curiously, into the deep annals of Ukraine’s existence. By the time they reach the journey’s end, however, readers are fully immersed in Ukraine’s colorful, virtuosic, and often overlooked and underdiscussed regions, peoples, and stories.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University