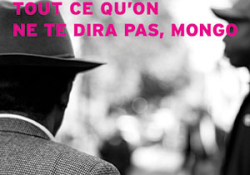

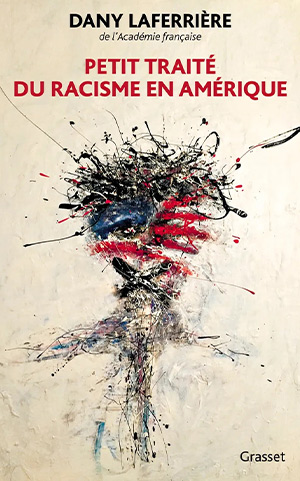

Petit traité du racisme en Amérique by Dany Laferrière

Paris. Grasset. 2023. 256 pages.

Paris. Grasset. 2023. 256 pages.

Born in Haiti in 1953, Dany Laferrière has been living abroad since 1976, mostly in Quebec, but also in Florida and in France. His first novel, How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired (Laferrière favors provocative titles), was published in 1985. Some of his books, all written in French, have been translated into English (his personal account of the massive earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010 was reviewed in the May 2013 issue of WLT). Others have been adapted into films (e.g., Heading South, directed by Laurent Cantet in 2005). In 2013 Laferrière became a member of the Académie française. After fourteen novels, mainly addressing topics related to identity and exile, his Petit traité du racisme en Amérique (Short treatise on racism in America) is his first book on the issue of racism. Dedicated to Bessie Smith, it is obviously influenced by the recent series of documented cases of African Americans who were murdered by white police officers, of which the best-known case is Derek Chauvin suffocating George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for nearly ten minutes.

Instead of a structured essay, this book offers a sort of kaleidoscopic arrangement of short texts, some in prose, some in a poetic format reminiscent of haikus (in 2008 Laferrière published a novel entitled I Am a Japanese Writer). Each section of the Petit traité, however short, has its own title. By way of illustration, here is a sampling of these titles: Le mot Nègre; La vie de l’autre; Blanc contre Noir; Le sentiment d’infériorité; La rage en Amérique; 9 min 29; La gloire d’Eleanor; L’afro d’Angela Davis; Langston Hughes à Port-au-Prince; Toni Morrison et Maya Angelou; Le Noir a peur du noir; Martin Luther King et René Lévesque.

Laferrière’s purpose in this book is not to provide a detailed accounting of all the recent deaths caused by racism. In a section entitled “L’esprit du livre,” he explains that he seeks to bring out the human “flesh and pain” that lies within “the tragedy that is racism” and to point out that in each case, it is “a human being who was killed . . . and not a concept.” His investigation of racism in America is more literary and psychological than historical or sociological. He points out that, due to his background as a Haitian exile living in Quebec and writing in French, his approach is somewhat different from that of other Black men and women who grew up in the United States. He also states that he is quite conscious of the levels of racism that exist in Canada or in France. He chose to write about America because of what he calls the “weight of numbers,” or the fact that the number of African Americans is higher than the total population of Canada. In the United States, where the descendants of slaves live among the descendants of slave-owners, the historical legacy of slavery and the Jim Crow era is much more pervasive and visible. Neither despairing nor naïvely hopeful in tone, Laferrière’s views on one of the most central problems of American society and culture are consistently insightful and thought-provoking.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University