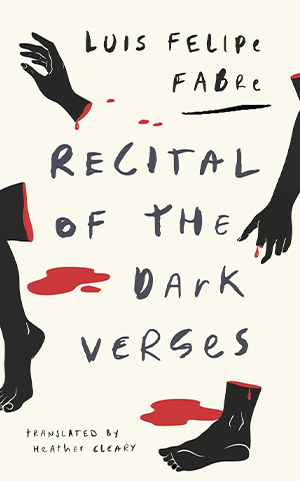

Recital of the Dark Verses by Luis Felipe Fabre

Dallas. Deep Vellum. 2023. 200 pages.

Dallas. Deep Vellum. 2023. 200 pages.

In Recital of the Dark Verses, Mexican poet and critic Luis Felipe Fabre takes the famous sixteenth-century verse of Carmelite mystic Juan de la Cruz (John of the Cross) and uses it as foundation for an insightful novel that pairs history with poetic commentary, the spiritual with the bawdy, and comedic adventures with existential reflections of mortality.

A bailiff arrives at a monastery in Úbeda, Spain, to secretly transport the body of Saint John to Segovia with the help of his two assistants, Ferrán and Diego. It is 1592, half a year following the death of the venerated mystical poet, but the exhumed body remains inexplicably well preserved, emitting perfumed aromas now cherished by the deceased’s Discalced Carmelite brethren. For the long, clandestine journey across the countryside, the bailiff decides the body will need to be first drained and given time to desiccate, lest decomposition set in during the midsummer journey and attract notice.

And so the seemingly simple transfer of a body to its intended final resting place starts with the first of many complications for the bailiff and his assistants. Likewise, thus begins the profane corruption of the sacred and venerated by human desires and greed. The seizure of the body by an agent of politics (the bailiff) soon becomes confounded by a seemingly supernatural heist, perhaps divinely ordained, only to thwart intended theft by yet others: local fervent devotees eager to hold onto the remains of their beloved saint. Or, at the very least, parts of him. Along with the saint’s body in tow, mystical visions and delirious confusion accompany the three men on their journey, as well as the lines of the mystic’s “On a Dark Night” reciting through their minds, mouths, and circumstances.

The thoughts and writings of Saint John of the Cross were dominated by an appreciation for the Song of Songs attributed to Solomon, one of the five megillot in the Ketuvim of Jewish scriptures that also became incorporated into the Christian Bible despite the poem’s controversy. The erotic nature of the text became interpreted as the love of Christ for the Church, and the reciprocal love of the Christian for Jesus. The sensual fervor of merging the sacred and profane in that text inspired the euphoria in the verse of Saint John of the Cross. Fabre takes hold of those same qualities in writing Recital of the Dark Verses, structuring the novel to incorporate them into layers of invented plot, historical events, and literary criticism.

“On a Dark Night” forms the thematic core of the novel, with the lines of St. John of the Cross’s poems being recited in full and in parts throughout the text, including one-sentence prefaces to each chapter that anticipate the events to befall the characters:

VIII. Wherein, still sheltered by the night of the first verse, having not yet left it behind but with entry swift becoming exit, expounded are its last two lines, which read, “I slipped out unminded / for my house had gone quiet,” and—dogged task—an attempt is made to commentate the abyssal silence that rifts this verse from the next.

Fabre also includes portions of two of the saint’s other best-known poems: “Love’s Living Flame” and “Spiritual Canticle.” Into these poems St. John incorporated personal experiences of imprisonment and escape that arose from persecution for his beliefs and writings. These nuances become prophetically paralleled to the events occurring to his body after death while handled by the bailiff and his assistants.

Those two assistants, Ferrán and Diego, serve as the comedic core of the novel, hapless and bumbling men of varying intelligence trying to earn some pay in what is supposed to be a simple job, but which instead constantly provokes them with inexplicable happenings and reminding them of their powerless and ignorant existence. Yet even amid mystifying wonder, they ironically resign themselves to experiencing joy in the mundane and lewd, whether taking a relieving piss “beneath the indifferent sky” or conversing in innuendo: “Why so surprised, ninny? Nuns are famous for their talent at threading the needle. They like their asparagus as much as the next lass.”

Fabre utilizes these two in a theatrical manner inspired by absurdist, existential works like Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead or Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Through their antics (along with the bailiff as more of a straight man), Fabre explores the theme of blindness/seeing and the way that language, through a few lines of verse, can make profound revelations that stretch across time and circumstances, even amid confusion in the dark.

“Do you believe that blind man was really an angel in disguise?” Diego asked his companion.

“No.”

“No?”

“No.”

“But you do remember what he said?”

“What?”

“About how when he looked into the waters of the fount he saw the face of the fable of the other sketched upon it.”

“No.”

“You remember it not?”

“He said it not.”

“What?”

“That was not what he said.”

“What did he say, then?”

“Gibberish unworthy of our remembrance is what he said,” said Ferrán.

And so the comedic, repetitive exchange of confusion continues, a mirror echoing an image that eventually shatters in a coming-of-age moment for the characters. A similar scene of theatricality revolving around blindness starts the novel, but here Fabre adds allusion to the myth of Narcissus. It is not the only Greek myth of vanity the story revives. The characters also parody the story of the Golden Apple of Discord during a spontaneous mock beauty pageant. With this Fabre ties together themes from the Song of Songs with the discourses of Proverbs: “all is vanity.” The direct use of theater or evocation of its spirit also cleverly reflects the merging of sacred and profane inherent to the art form, a type of communal worship that imparts morals while also entertaining.

Though short and structured simply, there is a profound complexity to Fabre’s Recital of the Dark Verses, one that evokes reader emotion and reflection throughout, whether a fan of poetry or not. Moreover, it contains a complexity of language to match the paradoxes of its themes. Flowery with moments of vulgarity, lyrical with moments of chaotic frenzy, the original Spanish must be difficult to translate straightforwardly into English. Translator Heather Cleary does a remarkable job letting Fabre’s brilliance and voice through, and her insightful introduction to the novel is integral to readers placing Recital of the Dark Verses into proper context, particularly if one is not familiar with St. John of the Cross, his work, and his history. I sincerely hope that Fabre writes further novels, and that Cleary will be there to English them so well.

Daniel P. Haeusser

Canisius College