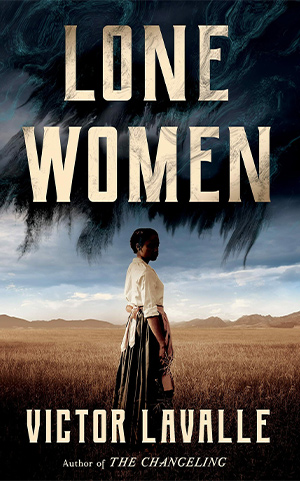

Lone Women by Victor LaValle

New York. One World. 2023. 304 pages.

New York. One World. 2023. 304 pages.

Both the epigraph to Victor LaValle’s new novel (taken from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon) and the opening paragraph conspire to capture the reader in a web of masterful storytelling. Immediately, attention is drawn to metaphorical flight. A thirty-year-old woman flees California with a massive steamer trunk and $154 in hopes of establishing a homestead in Montana. Yet she is haunted by her mother’s assessment of women as mules and her secret concerning the deaths of her parents. Adelaide Henry believes that lone women can have success in life. Yet there are few Black women in early twentieth-century western United States. The women she meets along the way enjoy varying degrees of success, and each has an enormous secret. Characters include a wealthy suffragette, a Black bootlegger, her Chinese lesbian lover and laundress, a schoolteacher unusually devoted to her son, and an utterly unrepentant scoundrel of a mother.

Told in three parts, the story beings in 1913, when a colony of Blacks have established claims in Lucerne, California. Adelaide and her mother and father are viewed as “queer folks” by the others in the colony. They largely keep to themselves, weighed down by a secret that prevents their complete socialization with others in the community.

In the work, women are foregrounded as either heroines or villains. That is to say, not all the women are good, and not all good women characters are without their imperfections. The reader suspects Adelaide of nefarious deeds as she hastens her departure from California and ultimately lands in Sandy Springs, Montana. Added to this, the narrator is a curious mix of the period and the present, certainly not quite early twentieth century and not objective in his storytelling—reminiscent of the narrator in Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage. While searching for Adelaide, who the town’s men believe is the cause of their ill luck, the leader of the vigilantes becomes enraged and the narrator observes, “The other men gathered in the doorway, watching Jack Reed losing his shit.” The women of the novel are unattached from men for a multitude of reasons. Yet they attempt to exist in the vast space that is late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Montana. The one attached character has complete control over her husband, Jack Reed, the leader of the vigilantes and among the richest men in town.

The novel has much to commend itself to readers. It’s captivating, and each chapter’s end leaves readers wanting more answers. It flirts with horror. Is there actually a creator “five stories high and just as wide,” or is it a matter of skewed perception: an inability to see? But the best part of the work is its delicate treatise on women and space—the space they are given to exist, by both men and other women.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University