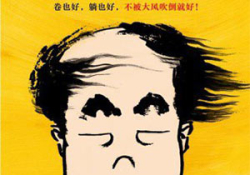

Crocodile (E Yu) by Mo Yan

Hangzhou. Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House. 2023. 197 pages.

Hangzhou. Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House. 2023. 197 pages.

Nobel laureate Mo Yan once swore in front of the Shakespeare statue in Stratford upon Avon to take advantage of the rest of his life to focus on the transition from novelist to playwright. The publication of his latest drama, E Yu (Crocodile), can be read as a brilliant delivery on that promise. During this process, as a successor to the oral literary tradition, Mo Yan continues to use comic styles in language, sometimes mixed with Chinese limericks and slang, contributing to the black humor of this play.

Drama has always played an important role in Mo Yan’s writing. Whether his debut work, Divorce (an unpublished play), or the dramatic elements in some novels, such as the interaction between traditional Chinese dramatic structures and novelistic text in Frog, it is no surprise to find that playwriting stems from his interests, rather than an alternate route he has taken in desperation. Just as Mo Yan admitted, “playwriting has been my dream for years. I do have a distinct understanding toward it. Besides, it is really enjoyable for the playwright to watch his plays performed on the stage.”

Crocodile revolves around a corrupt government official who subverts these legitimate governmental processes, misspends the public’s money, and finally escapes to another country. Its anticorruption consciousness not only keeps up to date with social developments but also contains unique cultural connotations, representing a rational reflection of the responsible writer on the cultural values related to government officials. Despite being rarely seen on the contemporary Chinese stage, this theme is familiar to the audience who has read Mo Yan’s novel The Republic of Wine.

Mo Yan insists that “writing is not on behalf of ordinary people, but as ordinary people.” It is worth noting that these down-to-earth experiences of sorting out files in the procuratorate and interviewing prosecutors provides him with much inspiration for this creation. Mo Yan examines many characters like intellectuals, officials, and businessmen through the lens of folk values. Shan Wudan, a dissociated defector, frequently mentions his concern for common people. Due to the fact that he sprang from peasant stock, this former mayor has a clear understanding about where political power comes from, thus frequently emphasizing the significance of the masses, pointing out that “there are some things unknown to God, but there is nothing unknown to ordinary people.”

The more compelling aspect of the play involves the crocodile being able to talk. Just like Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, the metaphor of animal here serves to highlight the alienation of human nature. As the embodiment of greedy human beings, the crocodile is confined to a tank with the characteristic that, once given enough space, will never stop growing. Over the past ten years, Shan Wudan keeps replacing the fish tank for “this birthday gift,” which finally became a four-meter-long behemoth. This is exactly the portrayal of the protagonist’s previous step toward corruption, symbolizing the infinite expansion of desire in society.

With a dehumanizing narrative form, Mo Yan constructs characters who are not human beings while integrating human desire, a critical position, and compassionate feelings, and then guides the audience to conduct a poignant critique of the events on the stage, further demonstrating the social responsibility of literary creators. In this sense, although Mo Yan is determined to cross another milestone, seeking breakthroughs in literary forms and themes, his spiritual core remains unchanged, that is, he is always concerned about modern China “as ordinary people.”

Zhang Min

Nanjing Normal University