Secondary Witnesses to the Holocaust: A Conversation with Ruth-Anne Damm & Sarah Hüttenberend

Bearing Witness: In his ongoing column, Karlos K. Hill highlights the efforts of cultural figures doing works of essential good around issues of social justice.

There are approximately 245,000 people still living today who survived the Holocaust. However, as more survivors inevitably pass away each year, whose responsibility is it to remember the Holocaust and keep it alive for those who will come after us? Zweitzeugen e.V. (Secondary Witnesses), a German educational nonprofit founded in 2012, trains German students to serve as secondary witnesses for the stories of Holocaust survivors. The organization’s founding principle is that connecting with survivors and then sharing their stories with others can create profound change for future generations. Zweitzeugen has interviewed thirty-seven Holocaust survivors to date, and more than 30,000 students have become secondary witnesses. In 2023 the organization received a prestigious Obermayer Award in recognition of the profound impact of its work. I interviewed co-founders Sarah Hüttenberend and Ruth-Anne Damm about the significance of Zweitzeugen’s work in light of the rise of anti-Semitic political movements in Germany in recent years.

Karlos Hill: Sarah and Ruth-Anne, before you became involved with this organization, what was your connection to the Holocaust and the survivor communities, and to the Jewish experience more broadly? What propelled you on the path to such specific work around memory and remembrance?

Ruth-Anne Damm: I don’t know why I had such an interest in the Holocaust as a child, but it started early for me. When I was in sixth grade, at the age of eleven or twelve, I took part in a reading competition at school, and the book I chose was Anne Frank’s diary. It was not a book suggested to me by a teacher; it was my personal decision to read it, even at such a young age.

An incident that happened when I was in second grade may have subconsciously set me on this path. I don’t remember how the subject of the Holocaust and Adolf Hitler came up at school that day, but when I got home and rang the doorbell so that my mother could let me in, she asked, “Who’s there?” over the intercom and I answered, “Heil, Hitler.” I was eight years old, so I had no idea what I was saying, but my mom was shocked. Instead of buzzing open the door, she came down to meet me, and I immediately knew that I’d done something bad. She sat me down, and I will never forget the conversation we had. I don’t know how long we sat there, but it seemed like hours. My mom took the time to explain to me how wrong it was to say what I had said, and why it was so wrong. She brought it to a very personal level. She told me about the Holocaust and how people were tortured and murdered in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. At that point I had no idea what it meant to be Jewish, but even at my young age, I understood that this terrible thing could have happened to my own family. I think the impact of that stayed with me. The older I got, the more I thought about my upbringing.

Something else that I think has been crucial for me personally is that people too often associate Germany with three things: Nazis, cars, and Oktoberfest. When I would visit another country and say, “Hi, I’m Ruth-Anne. I’m from Germany,” people’s reactions often made me feel like I had “Nazi Germany” stamped on my forehead. It was heartbreaking for me as a teenager to be lumped in with the Nazis, as if I had something to do with what they did. I think it has gotten better over the years, but back in the 1990s and early 2000s it happened a lot. I couldn’t understand it. So it was important for me to understand what happened here.

Sarah Hüttenberend: My own connection to the Holocaust as a young girl was through books. I have always been a curious person with a lot of empathy, and I have always had an interest in people’s stories. I grew up in a Christian family, with no connections to Jewish people at all, so I don’t have a family background on this topic, but I grew up in Germany, with parents who were a lot closer to the Holocaust than our generation is. They made it a mission to raise their children with democratic values. My parents have always been active in terms of helping people and being there for their community, so that’s something else that helped pave the way for me.

We talked about the Holocaust at school, of course, but it was the historical novels and stories about the Holocaust that I started reading when I was a teenager which really affected me. I ended up diving pretty deep into the topic on my own. So while it wasn’t my family upbringing that led me to the organization of Zweitzeugen, I did come to it with an interest in people and a great passion for fairness. I guess I’m someone who naturally builds bridges, and I was eager to use that skill in a way that helps people understand how to live together.

It was the historical novels and stories about the Holocaust that I started reading when I was a teenager which really affected me. —Sarah Hüttenberend

Hill: Now that we have a better understanding of your relationship to this subject and what brought you to the work you’re doing, can you explain how you connected with each other, and how you went on to collaborate in creating Zweitzeugen?

Hüttenberend: Zweitzeugen actually grew out of a student project that I started with a mutual friend of ours named Anna. We wanted to interview someone who had witnessed the Holocaust, with the intention of bringing that person’s story to a personal level and making it possible to see the whole person. When we talk about the Holocaust in Germany, it’s a historical topic from a precise time period. It has a beginning, and it then has an end with the conclusion of the war. But the people who survived it are more than that. They were children before the war with dreams and visions for their futures, and after the war they were still people, with their struggles but also their whims in life. We wanted to ask them a question that had never been answered for us in school: “What happened to you after the war ended? How were you able to move forward?” So it started as a mission to bring out survivors’ stories, but we also were looking for a way to connect people to other people’s lives.

Anna and I were fired up by this experience, but we didn’t really know what to do with these stories. We didn’t know how to make what we were doing more than a student project. We certainly didn’t plan on creating an organization. But then we met Ruth-Anne. She started out by helping us translate our interviews into English. But as she listened to the interviews in the process of translating them, we saw her diving into them so deeply, with such an open heart, that it was obvious she was the one with the expansive vision. She was able to take our idea and run with it.

Hill: At what point did you step back and say, “This is our mission now; this is something we’re committed to”?

Damm: It might seem like we had this big vision for Zweitzeugen right from the outset, but that wasn’t the case. We had no idea that we would grow our project into an organization like we have today. And I certainly didn’t believe that thirteen years later we would still be doing this. We took it one step at a time, and each time someone showed appreciation for our work, we got a bit stronger and braver.

When Anna’s sister was studying to be an elementary schoolteacher, she had a professor who was teaching Holocaust education. And that led to the question of whether we could bring what we were doing to young children. We didn’t know if it would work, but we were open to giving it a try. The more we did, the more people started coming in. This person would meet that person, who would introduce them to another person, and so on, and soon people were bringing in their own ideas and their own talents.

At the point when I was brought in to translate survivors’ stories, I had never met anyone who lived through the Holocaust. So I became a secondary witness before I ever met a Holocaust survivor in person. Since then, of course, I have met and interviewed many survivors. This is a powerful way of giving testimony and bearing witness. We are approaching the time when we will no longer be able to ask Holocaust survivors for their stories directly, but because of our work, I know that a hundred years from now, people who are willing to immerse themselves in these personal stories will still be able to become a secondary witness of this time.

We are approaching the time when we will no longer be able to ask Holocaust survivors for their stories directly. —Ruth-Anne Damm

Hill: When you’re able to get so close to your subjects, it helps you understand things about them that you otherwise wouldn’t be able to. It gives you a much clearer view. But sometimes do you get so close that maybe you see too much?

Damm: Yes, and that can be painful. It’s much easier to live in a bubble and not think about sad things, but these stories need to be told. As I listened to the voices of survivors through my earphones, and as I googled the places being mentioned, I found myself getting much more deeply involved in it all. At some point I could no longer do the work at home anymore because it was too emotional for me; I had to go to the university library and do it there.

Sarah had an experience that was particularly powerful for me. A survivor named Frieda, who was born in Warsaw in 1921, said to her, “Sarah, you’re a young woman. You should go out. You should dance and you should laugh. Why do you deal with the Holocaust?” And Sarah said something like, “I can still go out and laugh and dance, but I can deal with the Holocaust, too. This is what is most important to me.”

Hüttenberend: I remember the first time I met Frieda, who was ninety years old at the time. It was a Jewish place where they were celebrating neighbors and love in the neighborhood, so people were exchanging presents. She invited me into her flat and said, “Look at all these gifts I got. There’s so much love in my life.” She was so happy, so full of spirit and life and strength. I had just met her, and she told me her whole life story. She could so easily have given up and been bitter and sad, but instead she had chosen to love her life and go on.

And that’s something that still drives me today. If Frieda was able to go on after what she had been through, I can do my part for this, too. When you’re sitting in front of someone who has experienced so much trauma and loss in their life, and they’re making jokes to help you feel better about hearing their story, it really affects you. I’ve found so much strength in every encounter we’ve had.

Hill: Reading the testimony of a survivor with the intention of bearing witness to it is a way of building your own relationship with the past. Through oral history, oral memory, you’re teaching students how to take a survivor’s account and share it almost like it was their own. Can you talk a bit about the impact that your work with the organization has had, and when you realized just how impactful it was?

Hüttenberend: We were students at the time, not renowned experts, so we didn’t start out with a lot of confidence. We weren’t yet doing it with passion. But we had developed this concept for young children, so we took our program into the schools. Our first workshop was at a Hauptschule, which is a school that provides a very basic secondary education, and the teachers there warned me beforehand that the students wouldn’t be able to focus for too long and wouldn’t be willing to read anything. We were already nervous, because it was our first presentation, and here they were apologizing for the kids before we had even started. But half an hour later, fifty children were sitting on the ground with our interview magazines in their hands, reading survivors’ stories in silence. These stories have the potential to reach the heart of everyone, especially kids who have been underestimated their whole life. The kids at that Hauptschule were proving their teachers wrong. That is when I felt the impact.

Damm: Of all the many classroom experiences I could recall, the one that Sarah just shared is the one that instantly came into my mind. As of today we have reached over 22,000 teenagers and children in Germany. That’s a crazy number. I think what touches me most deeply is to see teenagers and children when they retell these survivors’ stories. There’s nothing more powerful for me than that. Whether they’re onstage, giving a talk, doing a podcast, making their own movie, or simply conversing with their peers, they’re finding a way to express this testimony they’ve learned, because they, too, have become secondary witnesses. I get goosebumps just thinking about it.

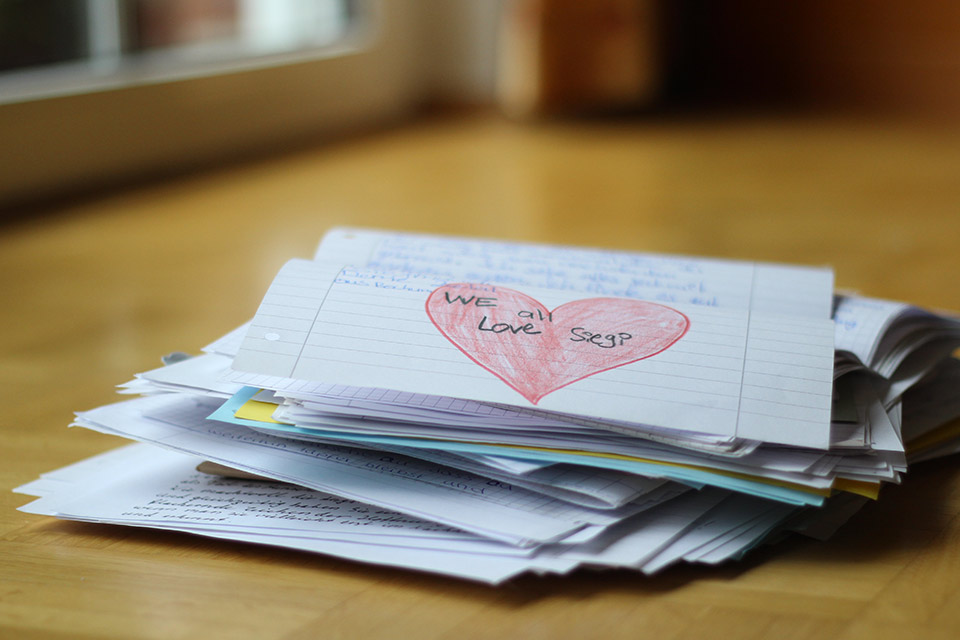

And there are few things that I find as emotional as reading letters that children have written to survivors. Imagine being a survivor and receiving your first letter from a child saying, “I heard your story and I’m so sorry about what happened. This is how it has affected me. I will never forget your story, and I’m going to retell it.” To read children’s words and then see the survivors’ reaction to them is truly life-changing.

Hill: A lot of the trauma associated with the Holocaust still shows up today, in the form of anti-Semitism and hate speech. How do we grapple with that? In my own work I try to get people to understand the past in the interest of helping them heal in relationship to that past. Do you see your own remembrance work as having a healing impact in how people relate to the Holocaust?

For the survivors, I question if there can be actual healing. But I can say that meeting us has had a healing effect. —Ruth-Anne Damm

Damm: For the survivors, I question if there can be actual healing. But I can say that meeting us has had a healing effect. Not with the past, since we can’t change what happened, but I do think it gives them a lot of hope for the future, to see that there are young people who want to understand and who are really, truly interested in their stories. We can’t do anything to change the past, but we can show the survivors that we are trying to change our present and our future so that history will never repeat itself. I think that is the power we can have.

Hüttenberend: Our modern society is really good at disconnecting—not just disconnecting from the past, but disconnecting from nature, from what we eat, from our emotions, even from elderly people and young people. Of course, it’s easier not to confront the truth of what’s not right in our society. But in doing this journey, I have learned the power of reconnecting. In order to reconnect to the past, you have to be open and let everything in. That’s not an easy thing to do, and it’s painful. But in my opinion, only by making meaningful connections to others can we truly come to understand why our society is the way it is right now. If we want to understand what makes people act the way they act, what disturbs them, what hurts them, we have to help people make real connections. And that’s what we are doing through our work with the past: letting this topic in, being open to feeling it, seeing its relevance for today, and being brave enough to go wherever it takes us.

Hill: Thank you for sharing so openly with me. It’s obvious how deeply you care about your mission. With hard work and courage, you have built what started as a student project into an organization that has already reached tens of thousands of young people, enabling them to serve as secondary witnesses for Holocaust survivors who can no longer tell their stories themselves. Bearing witness to victims and survivors is important and powerful work, and I have no doubt that others will be inspired by your efforts.

April 2024

Ruth-Anne Damm is co-founder, managing director, and chairwoman of the award-winning association Zweitzeugen e.V. As a secondary witness, she dedicates herself with great passion and vision to an active culture of remembrance and work combatting anti-Semitism. She previously worked to promote educational equity as a strategic brand consultant and in the NGO sector.

Ruth-Anne Damm is co-founder, managing director, and chairwoman of the award-winning association Zweitzeugen e.V. As a secondary witness, she dedicates herself with great passion and vision to an active culture of remembrance and work combatting anti-Semitism. She previously worked to promote educational equity as a strategic brand consultant and in the NGO sector.

Motivated to bridge the gap between information and people, Sarah Hüttenberend studied communication science and design. She grew up with a strong commitment to the fundamental values of social justice and charity. Deeply touched by the stories of Holocaust survivors, she founded Zweitzeugen e.V. and since then focuses on keeping their stories alive. She is a member of the board and leadership team of Zweitzeugen e.V.

Motivated to bridge the gap between information and people, Sarah Hüttenberend studied communication science and design. She grew up with a strong commitment to the fundamental values of social justice and charity. Deeply touched by the stories of Holocaust survivors, she founded Zweitzeugen e.V. and since then focuses on keeping their stories alive. She is a member of the board and leadership team of Zweitzeugen e.V.