Two Poems from Didxazá

[Dxapahuiini’ lu té]

Dxapahuiini’ lu té

Dxapahuiini’ cá dxiibi’ guié lu

Dxapahuiini’ ni biniti guendaruxidxi lade yoo

Bidii naa guiladxe’ dxiibi ladilu’

Lulu’ zundube’ nisadxu’ni xuba’

Guie’ daana’ niza sti’ gue’tu’

saguibe’ dechelu’

ti gué binniguenda cayati nisa

binniguenda daguyoo lu guidxilayú di’

Bidii naa gutiidena’ya’ ique lagalu’

ti qui chu’ dxi guibigueta’ dxiibi’ luguialu’

Ti dxita bere zutiide ladilu’

ra cá guiapa’ xtuxu bezalú ni cayuniná lii

Ti guiiñayaa xhube’ ndaani’ xiganalu’

ti guiana guendaruuyadxi ne bi dxaba’

gacaladxi’ guicá luguialu’

[Niña de pálido rostro]

Niña de pálido rostro

Niña que trae el espanto grabado en la piedra de sus ojos

Niña que perdió su sonrisa en los callejones oscuros

Déjame correr el miedo de tu cuerpo

Sobre tu rostro soplaré el anisado

El cordoncillo agua de los muertos

en tu espalda sacudiré

para dar de beber al sediento espíritu

que atrapado en este mundo permanece

Deja que mis manos acaricien tus párpados

para que nunca más se instale el miedo en ti

Un huevo de gallina recorrerá tu cuerpo

y en él se guardarán los ojos que te dañan

Un chile verde frotaré en la jícara de tus manos

así arderán las miradas con aire de maldad

que sobre ti se quieran posar

[Girl with a face so pale]

Girl with a face so pale

Girl with fear engraved on her onyx eyes

Girl who lost her smile in dark alleyways

Let me chase the fear from your body

I will bathe your face with anisado

I will sweep your back with sprigs

of spiked pepper quenching the thirst

of the greedy ghost haunting you

still trapped in our world

Let my hands caress your eyelids

to wipe away your fear forever

I will pass this egg over your body

to blunt the sharpness of the evil eye

I will rub a green chile in your cupped palms

to burn away any evil thoughts

that might fall upon you

* * *

[Rari’ nga guixalenu]

Rari’ nga guixalenu

Ladilu’ zabigueta ndaani’ guidxilayú

Cusaanadu lii ra yooba’

Rari’ zaziila’dxilu’

Lu gadxe gubidxa zeda ganadu lii

ziupanedu guie’ daana’

ne guie’ nayeche’

Zedanenu nisa ne gui’ri’

Západu guendabiaani’

ni gudxigueta’ laadu ra nuulu’

[Esta es la hora del adiós]

Esta es la hora del adiós

Tu cuerpo material vuelve a la tierra

Te dejamos en el yooba’

Aquí descansarás

Cada séptimo día te visitaremos

vendremos con cordoncillos

y flores alegres

Traeremos agua y veladoras

Tendremos memoria

para volver siempre a ti

[This is the hour for goodbyes]

This is the hour for goodbyes

Your physical body returns to the earth

We leave you in the house of the dead

So you may rest

Every seventh day we will visit

bringing you sprigs of spiked pepper

and vibrant flowers

We will bring water and candles

We will guard your memory

and return to you always

Translations from the Didxazá & Spanish

Translator’s Note

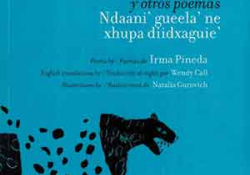

by Wendy Call

These two poems are part of an unpublished manuscript by Irma Pineda, a Binnizá (Isthmus Zapotec) poet in southern Mexico who has published ten collections of bilingual Didxazá (Isthmus Zapotec)-Spanish poetry. This manuscript, Ti guianda ti guenda / Para sanar un alma (To heal the soul), is inspired by the wisdom, knowledge, and experiences of midwives and traditional healers in Pineda’s home community. These poems document and celebrate traditional Isthmus Zapotec healing practices that are in danger of being lost.

Irma Pineda and I have collaborated since 2008 to bring her poetry into English. A neighbor of mine in Seattle, who is from Pineda’s home community, had asked me a year earlier to translate a few of her poems. Those poems stayed with me long after I completed the translation, and so I wrote to Pineda to ask her whether I might translate more of her work. Six weeks after I wrote to her, a well-traveled envelope arrived in my mailbox, containing four of her books and a warm note encouraging me to translate and seek publication of whatever I wished. Since then, I’ve translated and published in English nearly all the poems contained in those books, working directly with Pineda both virtually and in person.

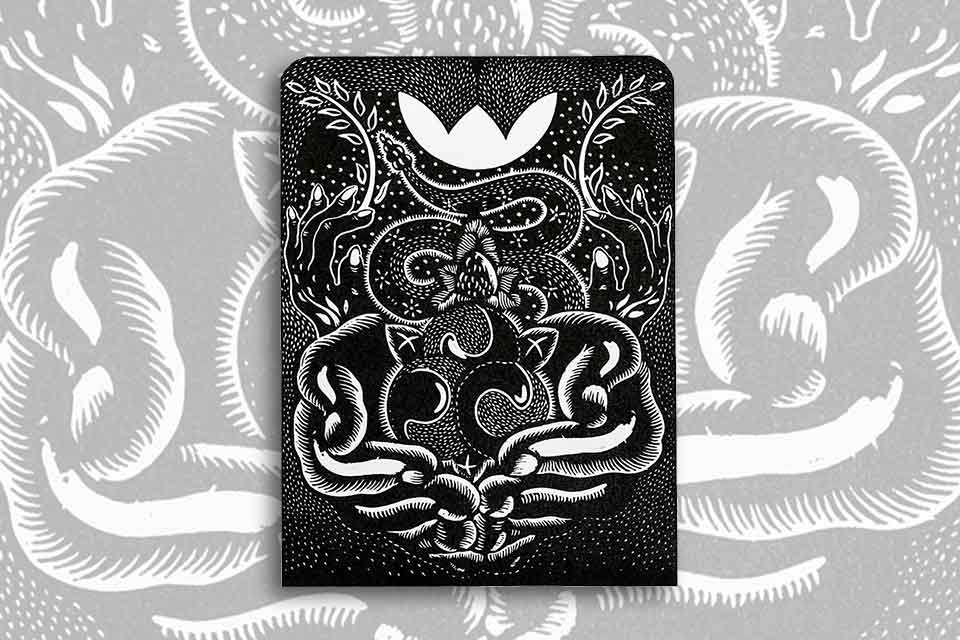

Pineda shared the manuscript for Ti guianda ti guenda / Para sanar un alma with me while she was still drafting it. The theme of healing—both physical and spiritual—weaves through every page of the book. The book’s forty-nine untitled poems form a sort of collective auto-ethnography, braiding together Pineda’s own experiences with information she has gathered about historical, traditional treatments as well as references to illness and healing in Zapotec history and literature.

In the first poem that appears here, with the first line “Girl with a face so pale,” Pineda tells in third person the story of a childhood experience. The poet was three years old when her father, a well-known teacher and Indigenous-rights activist, Victor “Yodo” Pineda, was forcibly disappeared. In the aftermath of that awful trauma, young Irma experienced a range of physical illnesses. One of them was dxiibi’ or espanto—a serious illness caused by deep shock or fear. A case of dxiibi’ is described here from the point of view of the curandera (traditional healer) who performed the limpia, or spiritual cleansing. The illness is caused by a binniguenda cayati nisa, “a thirsty ghost,” who is also a binniguenda daguyoo, “a ghost trapped in the house” of the living. This deceased person is “still trapped in our world,” Pineda explains, because of something important left unresolved in the person’s life.

With every line that I translate of Pineda’s bilingual poetry, I have the choice between following the Zapotec or the Spanish versions most closely. Occasionally, I diverge slightly from both. For example, the word for “eye” in Isthmus Zapotec is guié lu—“stone of the face”—which Pineda brought into her Spanish version as “piedra de sus ojos” or “stone of her eyes.” I, in turn, translated the term into English as “her onyx eyes.”

In the second poem, which begins “This is the hour for goodbyes,” the deceased person has finally been able to leave the realm of the living and travel to their final resting place. Unlike Pineda’s family members, who have lived forty-five years without knowing what happened to the poet’s father, Victor Pineda, the mourners of the deceased person in this poem are able to visit the cemetery, “the house of the dead,” every Sunday. They bring as an offering the same boughs of spiked pepper (cordoncillo or guie’ daana’) that are mentioned in the first poem, as part of the limpia treatment. They also bring water, so the person’s spirit will never be thirsty, and candles to light the spirit’s way through the inner world—the realm of the Zapotec afterlife.

Both the poet, Irma Pineda, and my Isthmus Zapotec teacher, Friddamir Romero, shared their time, expertise, and patience with me as I translated these poems. Their generosity is an enormous gift. Pineda devotes much time and energy to helping me translate her work into English because, she says, “Translation doesn’t only allow us to build bridges between one language and another. For Indigenous communities like mine, it is fundamental, because the translation process opens a window for us to see into other worlds. In addition, other cultures can learn a bit about our Indigenous communities. I believe this is a way to make them more sensitive and begin to address discrimination and racism.”

In the fifteen years since I received that battered envelope from Pineda with her first four books, she has published another seven books of bilingual Zapotec-Spanish poetry. I have translated at least a few poems from each of those seven books into English. The next collection of her trilingual Isthmus Zapotec–Spanish–English poetry, Nostalgia Doesn’t Flow Away Like Riverwater, will be published by Deep Vellum in January 2024. Meanwhile, I am seeking a publisher for English editions of two more of her books, including the one that contains these two poems, To Heal the Soul.