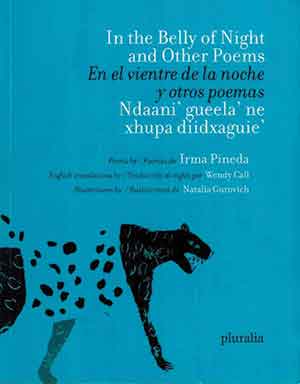

In the Belly of the Night and Other Poems / En el vientre de la noche y otros poemas / Ndaani’ Gueela’ ne xhupa diidxaguie’ by Irma Pineda

Illus. Natalia Gurovich. Mexico City. Pluralia Ediciones e Impresiones. 2021. 160 pages.

Illus. Natalia Gurovich. Mexico City. Pluralia Ediciones e Impresiones. 2021. 160 pages.

TO PUBLISH POETRY written in endangered Indigenous languages not only preserves the language but also a way of knowing, which is often an alternative epistemology. The work of poet Irma Pineda is no exception. She writes in Isthmus Zapotec, from her rural small town in Oaxaca, Mexico, where the number of speakers is dwindling rapidly. She also writes in Spanish in what she considers to be “mirror poems” rather than denotative translations of each other. To accommodate both versions in a single English version, translator Wendy Call sat with the author, Pineda, who explained just how each poem is shaped, and the kinds of wordplay that each has, and why. In investigating the differences, core ideas about the world and systems of knowledge came to light.

For example, in Spanish, en el vientre means “in the belly.” However, Gueela does not mean belly or intestines at all but umbilical cord. Further, the umbilical cord is inextricably linked to the house where one was born, because, after birth, the umbilical cord is placed in a small pot, which is then buried under the house. The earth and the body have a unique connection that does not occur with the Spanish colonial impositional culture. The fact that the translator spent time to learn about the embedded beliefs and traditions, and to incorporate them into her English translation, and to explain the process in the preface, is a great contribution to an understanding of the Isthmus Zapotec culture and poetic output.

The themes in the clusters of poems include the concept of the guenda, which is simultaneously spirit and animal. “Sun” reflects an animistic view of the world, where objects in the natural world can take on human traits and then shape-shift back. Similarly, the crocodile’s eggs swim just as the observer’s mind opens to the fecundity of all things and to unbreakable (albeit not always visible) connections. An animist perception of the world is also apparent in a poem from the first cluster of poems, “Red Belt,” where the red ribbon wrapped around the narrator’s pregnant belly both adorns and protects. The final cluster of poems, “From the Cord House to the Nine Handspans,” incorporates Isthmus Zapotec traditions while reflecting on the deep love the narrator has for Sebastian in his journey through life, from the “[umbilical] cord house” where he was born to the “nine handspans” (the grave, nine handspans below the surface of the earth).

Knowing that Pineda is writing from her home in Mexico City—and lives in a kind of self-imposed exile from the cluster of Isthmus Zapotec speakers she grew up with—adds another level of loss and nostalgia.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma