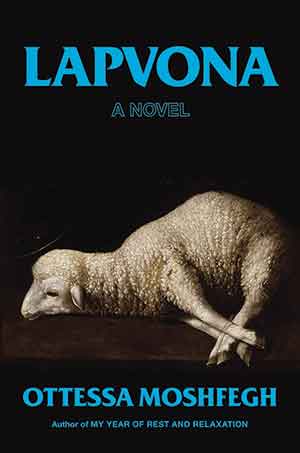

Lapvona by Ottessa Moshfegh

New York. Penguin. 2022. 320 pages.

New York. Penguin. 2022. 320 pages.

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH’S Lapvona is a study in power. It is an autopsy of the gaping gulf between abundance and misery, orchestrated by Villiam, the king of the eponymous medieval village, and his religious aide, Father Barnabas. From their hilltop, they control the fates of the Lapvonians below and puppeteer the bandits who plunder the villagers from time to time at the faintest sniff of brewing revolt. Lapvona navigates a variety of ideas—blindness and sight, the transposition of an internal ugliness to an external physicality, religion and power, the shifting lines between living and survival, isolation and madness—and each character is bound to multiple themes with staggering complexity.

Across her novels, Moshfegh has created a posse of unlikeable people—from the grotesque to the shallow and the neurotic—who are set up to be despised, but her genius lies in being able to build a deeply gripping world despite them—or perhaps because of them. The convolution of their thoughts and actions, sometimes indefensible, creates captivating narratives of unconventional lives. Lapvona has no dearth of such characters. The abusive lamb herder, Jude, simmers with unrestricted violence, both in love and in hatred, while his traumatized son, Marek, with a twisted spine, is steeped in self-flagellation and self-pity. His mute mother, Agata, whom Marek believes died in childbirth, moves from one religious institution to another before ending up in Villiam’s palace, witnessing the corruption and squalor that mark these institutions. The palace servant, Lispeth, nurses a deep hatred for the royalty, and yet there is not one crack in her steely veneer by which this hatred finds a vent. Ina, the eerie and supernaturally gifted village seer, shares a turbulent relationship with animals, which deteriorates from nurturing into terrifying. However, the shallowness of Lapvona is not a deliberate device employed to generate discomfort. It is the flotsam of characters who, despite being crafted in highly compelling molds, are unable to show development or movement, steadily devolving into caricatured versions of themselves.

Through the quagmire of suffering and destitution, consumption emerges as a leitmotif, indelibly altering the people on both ends of the chain. The characters share intricate relationships with the act of eating—Villiam is depicted as an empty pit into which food disappears, a close allegory of his hunger of power, never to be satiated. Lispeth views eating as an act of ritual, living proudly on the bare minimum, disdainful of those who need more to sustain themselves. Ina suckles the entire village, an act of universal surrogacy that extends well into the adulthood of the men who return to suckle her from time to time. Driven to cannibalism by the drought, she revives from near-death by consuming the flesh of a dead man, an event that fundamentally skews her relationship with the natural world.

Religion serves as the glove of power, employed in diametrically opposite ways by Villiam and Father Barnabas, on one hand, and the Lapvonians on the other. Jude impresses upon Marek that suffering is the key to earning the grace of God, but it is later revealed they do not know the origin of Christmas. Villiam and Father Barnabas use religion to justify the destruction for which they are responsible, dubbing it as a necessity that is mandated by the church and by God. The intertwining of the church and the state in the novel serves as a scathing commentary on the more subtle collusions within forms of power in the contemporary world.

While Lapvona is a great shift from the usual themes Moshfegh integrates, what remains intact are the scatological and physiological elements that mark her characters and the visceral nature of her writing. Lapvona can be especially difficult to read because of the unsentimental gaze that Moshfegh adopts in her unsparing narration of killings, rapes, witchcraft, and mutilations. The coldness in the narration of violence constructs a bleak emotional landscape, something she employs with deftness and precision. Considering her existing body of work, Lapvona is a leap in a significantly different direction but never far from the starkness that is evidence of Moshfegh’s brilliance.

Ashmita Chatterjee

Kolkata

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support