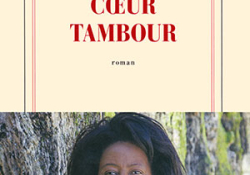

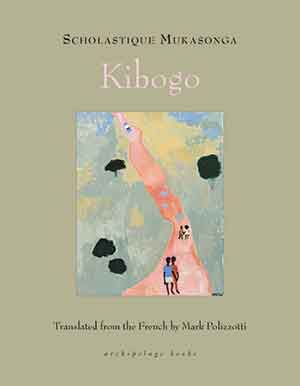

Kibogo by Scholastique Mukasonga

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2022. 152 pages.

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2022. 152 pages.

SCHOLASTIQUE MUKASONGA’S family was massacred in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Mukasonga was elsewhere and missed the carnage; forcing her to become a “survivor,” a term she inhales with angry bitterness. She eventually made it to France, where she married, had two sons, and became a social worker. But her much-acclaimed writing was always wrapped up in the hellish reality of Rwanda and all it had stolen from her. Her earlier works are mostly mournful tales told to us in a deceptively simple narrative voice that doesn’t quite suppress the urgency that lay beneath it. She was always trying to pay homage to her dead family, and the reader senses the strain was often overbearing. Her wrenching, autobiographically tinged works, like The Barefoot Woman, reminded me of the tortured prose of another survivor, Elie Wiesel, who, like Mukasonga, wore the damage of what had happened to him on his ravaged face.

In another of her works, Cockroaches, she writes about the guilt that is always present; her regret that she wasn’t “with her family when they were being hacked up by machetes. How could I have simply gone on living my life, as they were all dying?” But she lets some light in. She recalls precious moments with her beloved mother, who would teach her to braid mats and weave baskets but never forget to remind her that she must stay on guard. They were being hunted by the Hutus, her mother told her, and they would go for a young Tutsi girl before anyone else. Again, Mukasonga’s sentences are clipped but carry beneath them an impending depravity.

Tutsis were hated in Rwanda. The Belgians thought them to be “foreign” and supported the Hutus, whom they viewed as authentic Rwandans. The Catholic Church also sided with the Hutus, believing the Tutsis to be in cahoots with unnamed dangerous forces. The irony was that these designations were purely speculatory based on hypothetical notions of what a genuine Rwandan is or should be. It is thought that the combination of these forces fueled the genocide that killed eight hundred thousand Tutsis; thirty-seven of her family among them.

Mukasonga, like Wiesel, made a promise to always bear witness to the tragedy that had befallen her. And she desperately wanted to remain faithful to that pledge. But the reader senses she needed to find a new way to do so that didn’t involve such personal agony. Perhaps by allowing herself to freefall backward in time to ancient Rwanda, she could once again embrace her countrymen without rancor.

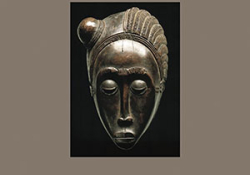

In her mesmerizing new set of interlinked stories, Kibogo, she embeds herself amidst the Rwandans of the past. It was a time when all Rwandans were considered the treasured children of the Kingdom of Rwanda. Hutus and Tutsis were seen as brothers in arms. The lively streets were filled with festive voices of people speaking her native tongue, Kinyarwanda, instead of the French she learned at school.

The story begins at a time when the townsfolk are desperate for rain. The Catholic priests blame them and explain the drought as related to their lack of enthusiasm for Catholicism. One priest admonishes the crowd: “But what do I see concealed beneath your medallions of Yezu and Maria? What are you trying to hide from me? Gris-gris that the witchdoctors made for you, that’s what, with all their bric-a-brac of leopard claws, warthog tusks, snakeskins, rabbit bones, twisted roots and feathers from those fortune-telling chickens that you don’t dare eat though you’re dying of starvation!”

But the people had grown weary of the clergy’s coldhearted condemnations, and a few decided to go in search of Kibogo, who had once brought the rain before disappearing atop a huge mountain into a white cloud. Their frantic search for Kibogo is fueled by the rantings of a renegade priest, Akeyuzu, who has recently been defrocked and was now preaching that the Bible could be interpreted in many ways. One could have their old beliefs and superstitions and Jesus, too. All of it was merely the same search for God’s grace.

Time passes, and the rain finally arrives, and most credit Kibogo. There’s a new feeling of defiance in the air with regard to the way the church condemns the Rwandans’ pagan beliefs. Some townsfolk are even whispering to one another about their anger at the plasticized stern Christianity being shoved down their throats. Newcomers visit the village and wish to spend time with the elders learning all they know about Rwanda’s grand past. They are infatuated with the elders’ stories, which they write down in notebooks as if a new sort of gospel.

Mukasonga rejoices in her ancestral homeland. It is a place of beauty and distraction where she wanders about, without being smothered by all that came later, which would ensnare her soon enough. We hear the chirpings of an unusual optimism sneak into the margins of her pages, and we rejoice alongside her. Mukasonga is an exquisitely original and sensitive writer.

Elaine Margolin

Merrick, New York

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support