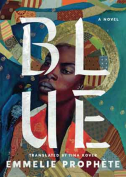

Dead Weight: A Memoir in Essays by Randall Horton

Evanston. Northwestern University Press. 2022. 134 pages.

Evanston. Northwestern University Press. 2022. 134 pages.

FROM BOETHIUS’S The Consolation of Philosophy to Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom, the history of prison writing is rich, and the US, with its two million incarcerated people, is, both de- and im-pressively, experiencing a surge; from Piper Kerman’s 2010 memoir Orange Is the New Black, which inspired the hit Netflix series, to Reginald Dwayne Betts’s 2021 award-winning poetry collection Felon. Randall Horton’s Dead Weight, though technically broader than prison writing, is a notable part of this movement.

It spirals inward and outward through a series of fourteen essays in three parts that encompass the author’s upbringing and first encounters with racism in 1960s and ’70s Birmingham, Alabama; his college cum crack-dealing and cocaine-running years in the ’80s; his descent into homelessness and addiction before being incarcerated and discovering writing in the ’90s; his return to college in the 2000s; and his achievement of becoming a professor at the University of New Haven. But this lifetime of events isn’t in easy chronological order, and the resulting leaps, associations, and repetitions are befitting of a collection that offers no singular perspectives or easy answers. Lyrical and brutal, street smart and philosophical, tender and tough, Dead Weight delights, disturbs, redeems, and instructs with kaleidoscopic style.

The opening essay, “The Protagonist in Somebody Else’s Melodrama,” which comprises all of part 1, takes place as a dialogue between Horton and Elizabeth Catlett’s bronze sculpture of Ralph Ellison’s invisible man near Riverbank State Park in West Harlem. Horton begins by relating to the wise but laconic sculpture, which he calls Cutout Man, his birth and childhood in the shadow of US race relations in the 1960s and ’70s. The language ranges from philosophical to earthy as Horton tells Cutout Man about being the only Black premature baby in the preemie ward in 1960s Birmingham, an all-white space that meant his mother couldn’t see him for the first eleven days of his life. About an imagined photo of this event, Horton writes, “Layered within the Polaroid negative of the photo would exist a textbook case of critical race theory, presenting a narrative of Blackness dreamed up by the likes of the philosopher Hegel with a target of ridicule on its back—underscoring what it means to be the other on plastic film.” And a page later, Horton records the imagined response of his friend Graveyard Pimp from nearby Titusville to the same event: “Mane, how you gone sit there and tell me some bullshit like that?” This kind of culture- and code-switching, or rheostating really, permeates the essays and underlies their complexity.

Part 2 of the collection begins with “November 2 and a Mother’s Love,” which opens, “On November 2, 2008, I cast a ballot for the first time in my life.” By the end of this piece, Horton escorts his mother, a longtime delegate for the National Education Association, to Obama’s inauguration and state dinner, and self, family, and national healing occur in DC, the same city where Horton encountered, contributed to, and endured the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s before going to prison. Part 2 continues with “Dead Weight,” in which Horton details his postrelease desire to attend an HBCU but is rejected by them, a struggle that he likens to learning to “negotiate the dead weight that attaches itself to the body after being discharged from prison.” Other essays from this section explore personal identity vis-à-vis limiting words such as felon and ex-felon, the power of poetry, and Horton’s contemporary work with at-risk youth and unjustly incarcerated people. (Of the latter, Horton writes, “This is the love the criminal justice system gives, as in, no love at all.”) It’s complex material but hopeful in tone. But Horton and this collection won’t let himself or his reader off so easily, and the essay “And So, It’s Complicated,” an unflinching meditation on the physical violence he witnessed and endured in DC in the mid-1990s, paves the way for the tough memories and deep soul-searching that come in part 3.

Five of the six essays that comprise part 3 are hard-hitting, as Horton, who we’ve come to admire, comes clean about his role as an aspiring street-level crack dealer who eventually lands a big-time connection with JC, a Colombian cartel-connected dealer in the Bahamas, and begins to build his East Coast empire with the help of select mules, or “transportation specialists” as he prefers to call them, and other means before “deception, jealousy, and greed” ruin things, leading to his homelessness and addiction. There’s a sense of community and loyalties, but menace, violence, and death run through everything due to the money and power at stake, money and power that Horton traces all the way up to the CIA’s probable involvement in the sale of confiscated cocaine to US dealers as a way to fund the Contras in Nicaragua. Along the way, Horton never shies away from his own damning and messed-up role in things, and the penultimate essay of the collection, “Archetypes and Disasters,” ends, “Forgive the fragmentation of this too-late apology and of every life I fucked up in the pursuit of selfishness.” Horton beats the reader to the judgmental punch every time, even while exploring the historical and societal pressures that contributed to his choices.

“The problem is mine alone to let go,” Horton muses as he seeks self-acceptance at the end of the collection after reflecting on all of the “damage done.” I appreciate this struggle and would add that systemic racism, a failed war on drugs, and mass incarceration are ongoing national problems we all need to better understand and address. Dead Weight is an important part of that effort as well as a sharp, gripping read.

Timothy Bradford

University of Oklahoma

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!