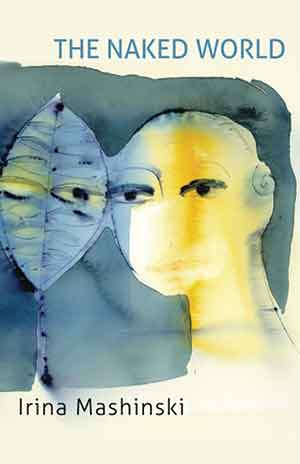

The Naked World: A Tale with Verse by Irina Mashinski

Cheshire, Massachusetts. MadHat Press. 2022. 185 pages.

Cheshire, Massachusetts. MadHat Press. 2022. 185 pages.

IRINA MASHINSKI IS one of the most notable contemporary Russian American translators and poets. While she usually composes poetry in Russian, in her latest work she writes in English to examine her family’s origins in the former Soviet Union and their exodus to the United States. In the preface, poet Ilya Kaminsky writes that Mashinski’s memoir is “a magical book, a story of four generations of one family, told through poems.” Mashinski, Kaminsky, and many others are labeled as Russian American writers, and their Judaism is often not mentioned or perhaps deemed unimportant by editors and publishers. Yet their experiences in the Soviet Union and the reasons they emigrated specifically transpired because of their Judaism. In the Soviet Union of Mashinksi’s childhood and early adult years, Jews had special marks in their passports, were prohibited from certain professions, and were not promoted in the jobs they could find. Children were called slurs and often beaten up just because they were Jewish. Mashinski’s memoir is magical, as Kaminsky writes, because she addresses her family’s Judaism through a combination of interconnected poetry and short essays.

The Soviet Union was formed to provide equality to all citizens, but it didn’t take long for Stalin to become wary of a perceived growing threat from Jews in the government. Mashinski’s family felt the effects of this distrust going back to her grandparents’ young adult years, specifically in 1928 when her paternal grandfather, Alexander, was arrested and imprisoned just before the birth of Mashinski’s father, Victor. Alexander’s brother-in-law, Sergei Gorny, had been the consul general in Turkey during the early years of the Soviet Union and was suddenly on the outs with Stalin. No family member was left untouched, and, because of this, Alexander was imprisoned for the first, but not last, time.

Mashinski writes about her paternal grandparents and their family separation in the essays “Alexander and Alexandra, The First Arrest” and “Victor,” followed by a poem, “Love”: “. . . counts her beads of trifles, / slips of tongue, quick glances, / having tortured millions / of crumpled petals, anguishing / from encounters, for one year watching / from the four corners, having not uttered / even two words.” Alexander would be arrested again twenty years later in 1948 and sent away for six years that time.

Mashinksi was born in Moscow in 1958, half a century after Jews had moved beyond the Pale of Settlement or what is now Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Moldova, and parts of Poland, Latvia, and Russia. Several million Jews were confined to this area from the late 1700s until the founding of the Soviet Union and murdered in pogroms en masse when economies declined or rulers felt the need to solidify their power. Another million Jews in Ukraine were shot to death in mass killings during World War II. Many Ashkenazi Jews around the world can trace their origins back to the Pale of Settlement, including Mashinski.

In her prose essay “The Bronze Horseman, Natasha,” Mashinski writes of her mother’s exodus from Kiev in 1941 just before the city fell to the Nazis. Mashinski’s mother, Natasha, was only nine years old when her mother, Ophelia, had the foresight to leave Kiev and head east for the Urals, away from Europe. Before they could flee, the Germans bombed their train. Ophelia acted quickly and put Natasha on a truck with relatives leaving the city. Thanks to her grandmother’s quick thinking, Mashinski is here today. In reading this essay, I could not help but reflect on today’s conflict in Kyiv, as it’s known in Ukrainian, as families are torn apart—if they survive. And that the number-one Jewish target of aggression in this current conflict happens to be the president of Ukraine, which would have been unheard of twenty years ago.

A number of former Soviet Jewish memoirs by authors like Yelena Lembersky (see WLT, May 2022, 22–25), Lev Golinkin, and Margarita Gokun Silver, among others, show how difficult it was for Jews to leave the Soviet Union during perestroika in the late 1980s and early 1990s when anti-Semitism was on the rise yet again. Jews who could leave would often not rest until they crossed borders by foot or train or until their flights left Soviet airspace. Mashinki’s essay “The Sheremetyevo Airport” is full of tension and unease as she and her young daughter try to leave Moscow. “Holding Sasha with one arm and a guitar with the other, I crossed over—straight into the lights of the duty-free zone. Ever since that night, I foolishly enjoy this commercial, artificial, heavily perfumed space—to me, it smells like freedom, and duty-free spells: free.” She vowed to never again allow herself to experience fear.

The United States did not always provide a warm entrée for Soviet Jews. This was at a time when the USSR was still viewed as the evil empire and typical American citizens were not normally educated about the persecution of Soviet Jews and their harrowing escapes mainly from the 1970s until the early 1990s. But the US did provide Soviet Jews with a chance to start over and escape persecution solely due to their heritage.

In “The Motif: The Myth,” which appears toward the end of the book, Mashinki provides a nice summary of this new start: “And then you grow up and emigrate, and, still surrounded by the people that were your kin, your kind, and your blood (or so you were told a long time ago)—you feel stark naked in the middle of a stark-naked world, in the empty field where your last name is suddenly the last and most arbitrary thing that matters to you; you find yourself in a space where your little myth becomes disconnected, disjointed, unassuming, useless, and—therefore—finally honest.”

Susan Blumberg-Kason

Hinsdale, Illinois

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!