A Poem from China in Memory of Liu Xiaobo

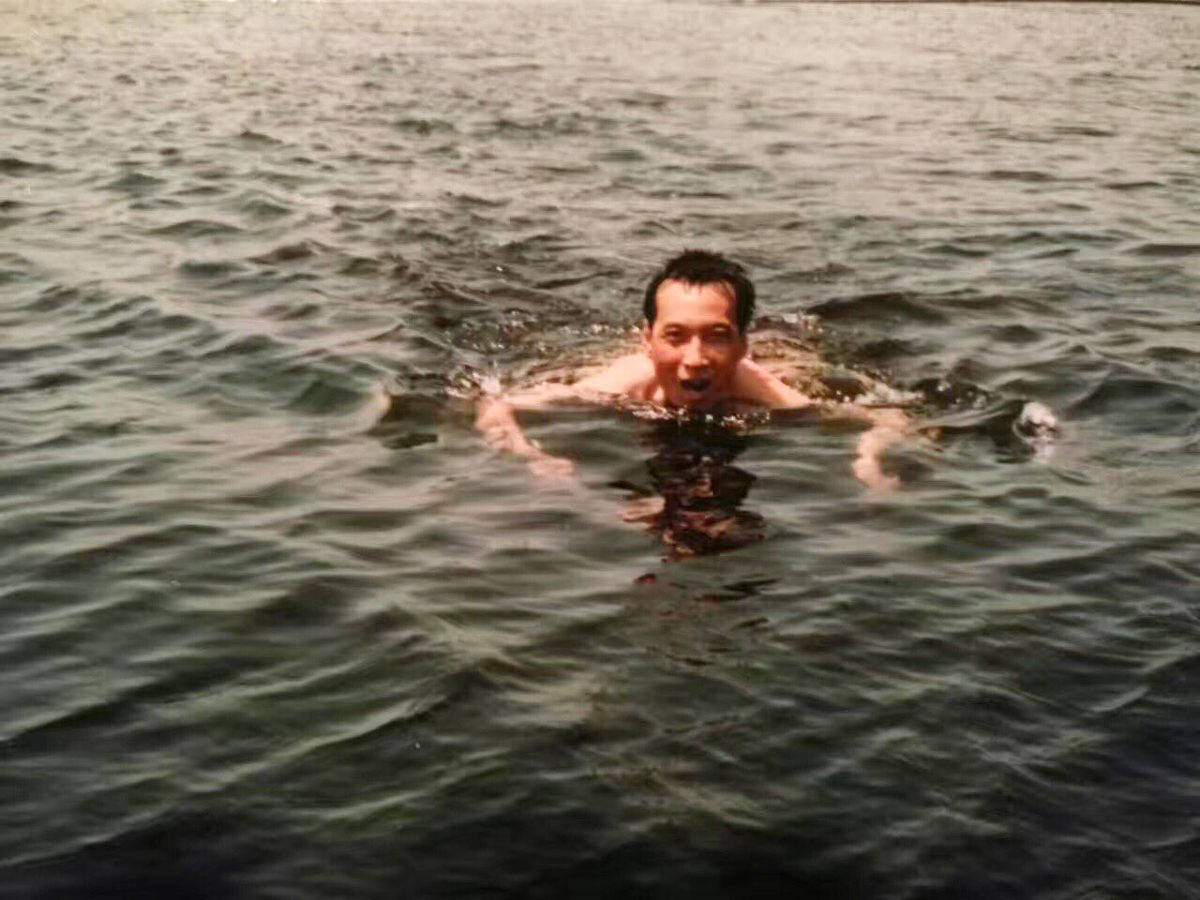

Translator’s note: This photo of Liu Xiaobo swimming surfaced on the Internet after the sea burial in Dalian, China. Those of us who were heartbroken by his sudden death felt a little bit relieved after seeing the photo—Xiaobo was a good swimmer and he’s now gone home, to the sea, free. Liu Xia’s first narrative poem was about the sea, in which a fisherman threw his only keepsake into the sea to preserve his memories of love. – Ming Di

Story of the Sea

1.

She kneels on the beach

weaving a fishing net,

her belly forward.

She rests a little to look at the sea,

a sea so boundless. No edges.

The fishing net splits her view

into small squares.

She is a fisherman’s wife.

She has always lived on this island,

never been away.

She has a red dress, worn only once

with the price tag still on it,

now at the bottom of a trunk.

She has dreamed of cities.

And city lights.

But it’s over. She will not share her dreams.

In the days her husband is gone to sea,

she talks to her son –

she’s sure it’s a boy – the one she carries

in her body.

She talks to him silently.

She is a fisherman’s wife.

2.

At dusk, a boy goes to the sea

holding his grandpa’s hand.

There are graves of various shapes

along the road, large and small,

with the clothes, quilts and bowls

that belonged to the old man’s friends –

they went to sea

but never returned.

The old man has made these graves

and mourned his fellow fishermen in tears.

He himself can no longer go to sea.

The boy walks along, jumping from one grave

to another, covered with grass

that brushes his legs like waves.

Every day the boy would go to the seaside

with his grandpa

who would sit on the beach

looking for a long time at the familiar, strange sea.

When it’s completely dark, the two of them

would leave the waves to the noise

and go home quietly like two sampans

sliding across the sea.

3.

Scattered on the beach are some boats,

old and mossy.

A little boy, bare-butt, is playing there

and suddenly finds something.

He cries out to the old man on the cliff

and runs to him with it.

The old man trembles at seeing it, a comb,

handcrafted, its teeth broken.

He had given this wooden comb

to a girl, so lovely and lively then,

and dated her in one of the now shattered boats,

an oil lamp casting light on their young faces.

Now his wife is dead.

There will be no more hair, long and black,

on their brick bed.

The old man shakes his head, speechless.

He throws the comb into the sea,

watching it drift afar.

1982

Translation from the Chinese

By Ming Di

Editorial note: Look for two additional poems by Liu Xia in the “Resistance” cover feature of WLT’s January 2018 issue.